When, in 1921, the Italian writer Gino Gori decided to convert the lower part of a hotel he owned in Rome into a nightclub inspired by Dante’s Commedia, he asked the futurist artist Fortunato Depero to create an ‘opera d’arte totale’. The term is borrowed from the German notion of Gesamtkunstwerk, at the time being pursued rather more rigorously at the Bauhaus; but it proves to be an apt phrase for the cabarets and nightclubs that feature in this imaginative and very enjoyable exhibition exploring their relationship with modern art.

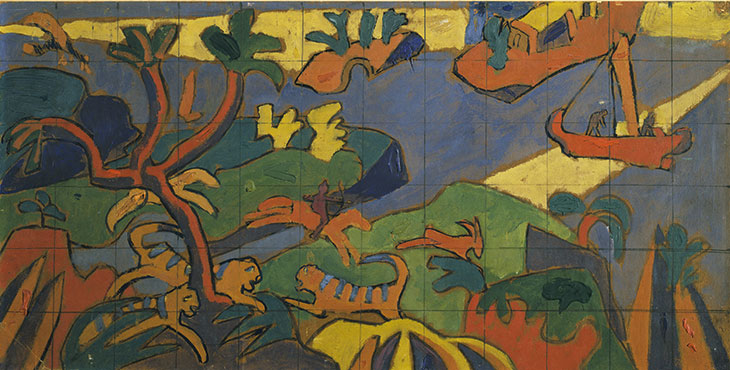

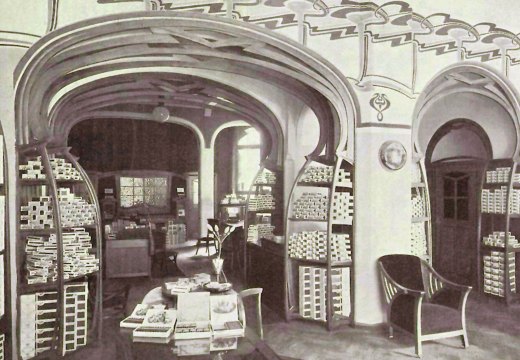

Artists were closely involved with cabaret from its very beginnings at Le Chat Noir in 1880s Paris, not only as patrons and recorders of the entertainment on offer but often, as with Depero, designing the buildings and decor. Cabaret Fledermaus (1907–13) in Vienna, for example, was the creation of the Wiener Werkstätte under the architect Josef Hoffmann: his designs for the cabaret’s furnishings encompassed not only its chairs, but also its ashtrays, pepper mills and vases; its basement bar was covered in 7,000 tiles created by the ceramicists Michael Powolny and Bertold Löffler, and its programmes were illustrated by Oskar Kokoschka. Similarly, the Cave of the Golden Calf in London (1912–14) featured murals by Spencer Gore, who recruited Jacob Epstein, Eric Gill, Charles Ginner and Wyndham Lewis to provide other decorations and design everything from drop curtains to menu cards. Missing from the exhibition (owing to problems with loans), but included in the excellent catalogue, is Moscow’s short-lived Café Pittoresque (1918), which had a dazzling ‘kinetic’ decor to which the constructivist artists Vladimir Tatlin and Alexander Rodchenko contributed.

Study for a mural decoration for the Cave of the Golden Calf, London (1912), Spencer Gore. Tate, London

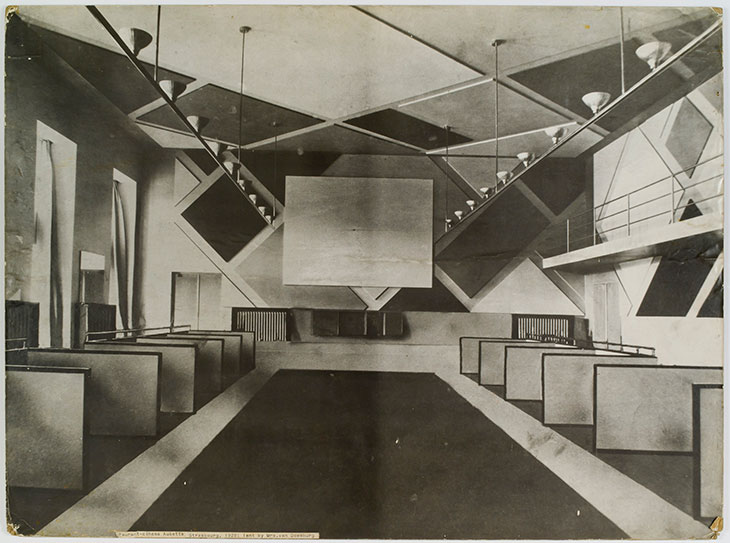

In other cities, too, cabaret embraced the avant-garde and was often associated with radical artistic or political movements. Dada famously evolved from the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, while L’Aubette in Strasbourg reflected the ideas of De Stijl and was described by Theo van Doesburg, who designed it, as ‘the beginning of a new era in art’. The Café de Nadie in Mexico City in the 1920s was where members of the revolutionary Estridentismo (‘Stridentism’) movement gathered to listen to music, exchange ideas, write manifestos and hold exhibitions of their bold woodcuts (very well represented in this exhibition).

The Ciné-bal (cinema-ballroom) at Café L’Aubette, Strasbourg (1926–28), designed by Theo van Doesburg. Image: Collection Het Nieuwe Instituut

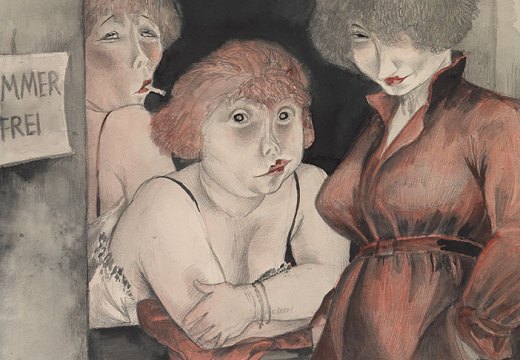

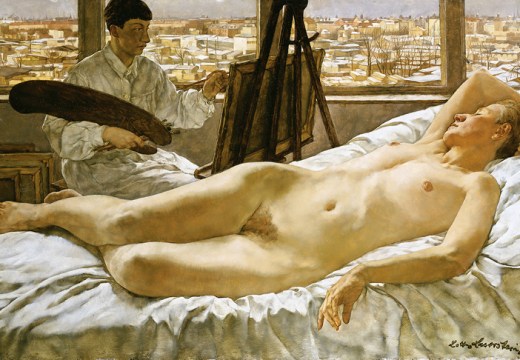

If not associated with particular artistic or political movements, other clubs and cabarets were in the vanguard of challenging conventional social attitudes, particularly those related to sex and race. The ones in Weimar Berlin were packed with cross-dressers and same-sex dancing partners, a world captured by such prominent artists as Otto Dix, George Grosz and the wonderful Jeanne Mammen. Berlin embraced jazz (and its associated graphic style) and welcomed Josephine Baker and other African American musicians, while in New York white tourists flocked to the black clubs in Harlem, which were also renowned for their drag balls and such sexually unorthodox performers as the white-tuxedo-clad Gladys Bentley and her ‘pansy chorus line’. The exuberance of the American clubs is brilliantly captured by an enthusiastic British visitor, Edward Burra, in Savoy Ballroom, Harlem (1934), nicely placed here alongside paintings by the African-American artists William H. Johnson and Jacob Lawrence.

‘Into the Night’ devotes 12 sections to individual cities, and is a well-judged mix of the familiar and less well known, its geographical reach extending beyond Europe and America to include Nigeria and Iran as well as Mexico. This may seem like a bid for modish inclusivity, but the Mbari clubs in Ibadan and Osogbo in the 1960s were places where modernist art and popular entertainment met just as they did in the West. Similarly, Rasht 29 in Tehran (1966–69) was a club for the city’s artistic community that featured poetry readings, music making and screenings of avant-garde films.

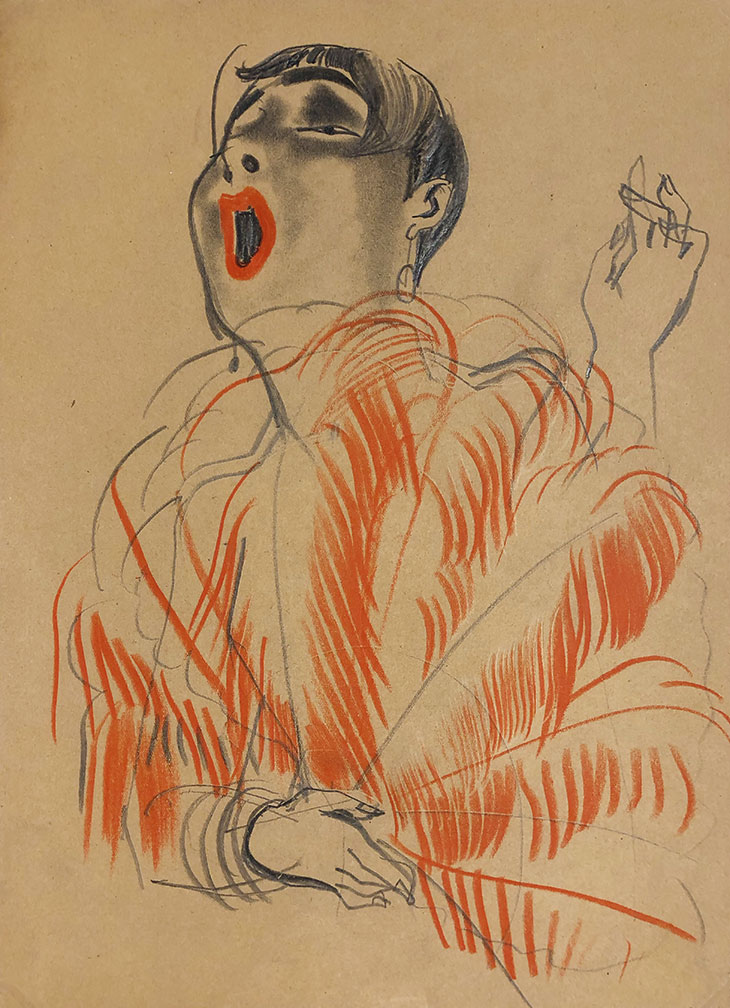

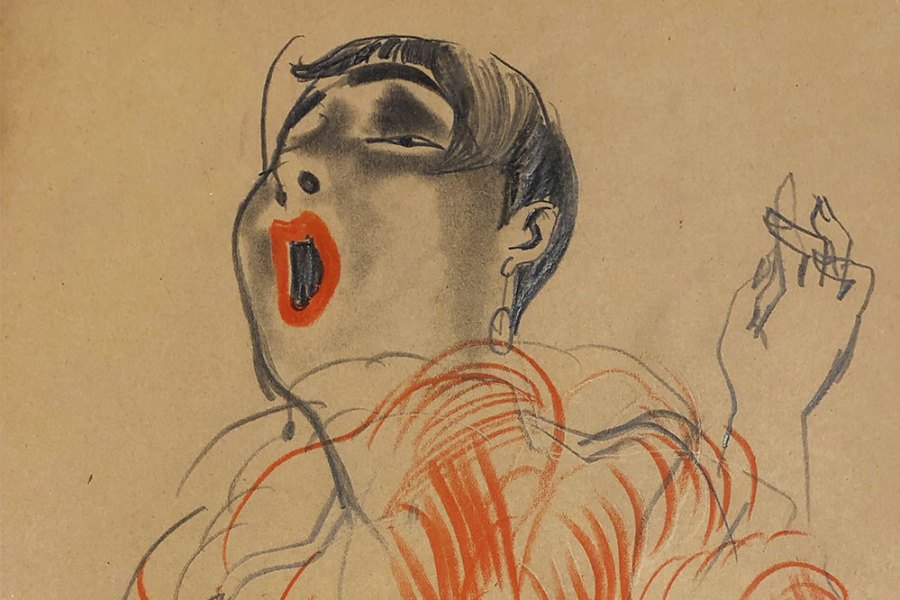

Chansonette (1928), Erna Schmidt-Caroll. Courtesy Salongalerie ‘Die Möwe’; © Estate Erna Schmidt-Caroll

Because cabarets and clubs were central to the cultural life of cities and embodied la vie de bohème, they attracted the attention of major artists. Nine of the 60 unique lithographs Toulouse-Lautrec made of the American dancer Loïe Fuller performing at the Folies Bergère in 1893 are on display. As a series, these lithographs recreate the colour variations (produced on stage by lighting) of the costume Fuller dramatically swirled around herself while performing her ‘Serpentine Dance’, and they can be instructively compared, in the same room, with Jules Chéret’s large posters of Fuller and a very early hand-coloured film of the dance. The welcome juxtaposition of famous artists and their less well-known contemporaries is particularly apparent in the section devoted to Berlin. Alongside works by Grosz, Dix, Beckmann and Mammen are two fine drawings by Erna Schmidt-Caroll, who didn’t even feature in a large exhibition in Frankfurt two years ago charting ‘Splendor and Misery in the Weimar Republic’. Her 1928 drawing of a chansonette embodies the era with beautiful economy, using red pastel crayon to circle the singer’s wide-open mouth and to indicate with loose strokes the large feather fan she is holding. Characteristic of the curators’ stimulating choices is that instead of Dix’s celebrated full-length portrait of the defiantly scandalous dancer Anita Berber, we have his 1925 pastel of her in which she looks a good deal more vulnerable – indeed, ravaged by drink and drugs, she would die three years later at the age of only 29. It is a pity, however, that the copy of Curt Moreck’s Guide to ‘Depraved’ Berlin (1931), to which several leading artists contributed illustrations, is open at an image of the lesbian Café Olala by Paul Kamm – all right as far as it goes, but not in the same league as the marvellous line drawings provided for the book by Christian Schad, an infinitely superior artist who is unrepresented here.

The least successful part of the exhibition are rooms devoted (often very sketchily) to ‘full-scale recreations of specific spaces’. The tiled interior of the Cabaret Fledermaus is certainly spectacular, but what is inevitably missing from these installations is the human element of performers and audience: the voices, the smoke, the clinking of bottles and glasses. This is, however, vividly apparent in the 300 or so paintings, prints, drawings and photographs on display in other rooms, which show that – for a time, at least – life could indeed be a cabaret.

‘Into the Night: Cabarets and Clubs in Modern Art’ is at the Barbican Art Gallery, London, until 19 January 2020.

From the November 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home