From the April 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

You could never accuse Charles Baudelaire of mincing words. On the bicentenary of the poet’s birth (which falls on 9 April), the collected pages of his art criticism still hum with a sense of outrage: a kind of personal offence-taking that he should have been subjected to so much bad art. The prevailing mood in his exhibition reviews (the ‘Salons’), despite his praise for modernity, is one of lament at living in a degraded and degrading time. He enters the show of 1859 in the Palais des Champs-Élysées with a sinking heart, and has it sunk even further at almost every turn. ‘That mediocrity has been dominant across the ages is without doubt,’ he writes in the ‘Salon of 1859’, ‘but that it reigns more firmly than ever, that it has become absolutely triumphant and stifling, is as true as it is afflicting.’ Everywhere ‘smallness, puerility, incuriosity, the dead calm of fatuousness have succeeded ardour, nobility, and turbulent ambition’. With one or two exceptions, ‘The artist today is, and has been for many years, […] a simple spoiled child’, an ‘imitator of imitators’ capable of a certain facile polish, incapable of anything you might call true art.

The question Baudelaire asks himself again and again in his art criticism is a direct, horrible one: à quoi bon? What is the point – of art, of criticism, of life? As he passes morosely through three Salons and one Exposition Universelle, he is whipped on by a hopeless fear of boredom. As in his poems, spleen stalks him everywhere, ready to turn the most pleasing prospect into ‘Des plaines de l’Ennui, profondes et désertes’. What he is searching for in the exhibition halls is a brute aesthetic force majeure: something that can stimulate even his jaded organs of perception.

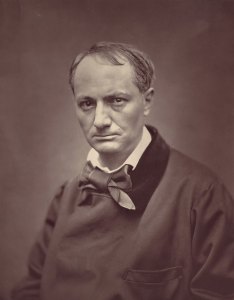

Charles Baudelaire (c. 1863), Etienne Carjat. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

It is not an easy task. The description he gave of himself in ‘Spleen’ sees him like the king of some rainy land: rich, impotent, bored almost literally to death in the midst of splendour, power and sensation. ‘Nothing cheers him,’ runs Robert Lowell’s memorable translation, ‘darts, tennis, falconry, / his people dying by the balcony; / the bawdry of the pet hermaphrodite / no longer gets him through a single night.’ He is desperate to find something that will snap him out of it. The products of the Salon artists do not stand a chance.

Little surprise, then, that most of what Baudelaire sees at the exhibitions is ‘boring’ (ennuyeux), which is why, he points out, articles about the Salons tend to be ‘boring’ too. He is even willing to write off whole art forms: though the verdict of doom softens in later years, one chapter of his review of the Salon of 1846 is titled simply ‘Why Sculpture is Boring’. He finds a few pieces here and there that he can pick out for qualified praise, but the general impression left by his writings on art is that he would be happiest of all if Delacroix – whose ‘fecundity and energy, as great as they are, cannot console us for their poverty in all the rest’ – were the only painter left alive in France. When he exits the grand hall of the Salon of 1859 he literally heaves a sigh of relief: ‘Finally, I can allow myself that irrepressible phew! let out by every simple mortal with his share of spleen who has been condemned to a forced march, at last permitted to throw himself down in the longed-for oasis of rest.’

It is easy to make fun of Baudelaire’s increasingly raddled teenage scowl, and that is certainly one of the pleasures his criticism affords. Time makes a fool of him, as it does all old critics. Beyond an appreciation for Delacroix and also Daumier, his taste from a contemporary standpoint seems almost deliberately contrary – and occasionally inexplicable. Irritated by Ingres’s finicky polish and ‘picturesque’ smoothness, he accuses the painter of being unable to take beauty as he finds it, of ‘inability to make [his model] at the same time great and true’. It is a reproach worth thinking about, but harder to take seriously once Baudelaire offers up Louis-Gustave Ricard as more deserving of the public’s praise. ‘Who?’, you might ask. Like plenty of Baudelaire’s favourites, Ricard is someone whom even the poet’s memorialisation has been unable to rescue from the genteel oblivion of the museum storeroom. Even more striking – or not – is ‘The Painter of Modern Life’ (1863), an essay that managed in a glancing throwaway to make the flâneur an iconic figure of modernity, while the actual painter in question, Constantin Guys, has faded to almost total obscurity. There is a reason editions of Baudelaire’s Écrits sur l’art tend to be somewhat light on reproductions.

Meeting in the Park (c. 1860), Constantin Guys. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The ease of poking fun, though, is precisely what is salutary about reading Baudelaire’s criticism. Baudelaire is not as unbending in his judgements as he sometimes seems, but he knows exactly what he wants: expressions of le beau, in learning (these Salon artists would not even read a cookbook), in the bizarre (beauty is always strange), and above all else, through imagination (queen of the faculties). By 19th-century standards, he is a radical, theorising the beauty of the strange, the vulgar, the common and the transient; questioning and complicating his standards. And yet he now seems fully of his time, too: haughty, snobbish, unreflective for all his reflection, taking its values and yardsticks for granted.

The 21st-century critic spends their time examining art from somewhere in the middle of a tangled interchange of standards: aesthetic, commercial, ethical, political. It feels easy to get lost. You envy Baudelaire his certainties, laugh at the absurdities they seem to produce. Then you find yourself asking how time will make a fool of you, and how simple and unwitting our own critical principles might one day seem.

From the April 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home