It does not take much to make a monster. In Léopold Chauveau’s long series of Paysages monstrueux (‘Monstrous Landscapes’), produced from the early 1920s up to his death in 1940, just about any outline will suffice. Reduced to the simplest of graphic gestures, the creatures that populate his landscapes range from fantastically distorted humanoid or animal forms to amorphous blobs. Occasionally they are even the landscape itself: the bare triangle of a mountain or rock given life. Animal, vegetable or mineral, they are for the most part just a cartoon outline filled with a flat wash of watercolour, but the viewer knows they are alive. The key is simple: eyes. Given eyes, any form becomes animate: mountains slumber, rocks or trees brood; other entities, free to move, acquire questing purpose. They discover their own bodies with surprise, examine the horizon, search out objects of interest. Above all, they are watchful.

You are unlikely to know the work of Léopold Chauveau (1870–1940). Currently being honoured with an exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay (until 13 September), he made little impact on the art world during his own lifetime. His monsters were, largely, a private pursuit, worked at during his long career as a doctor, children’s writer and novelist – most of them unseen until now. And yet, they are instantly familiar figures: embodiments, in all their variety, of a particular kind of monstrous figure that has stalked modernity, watchful and wary, for the last two centuries.

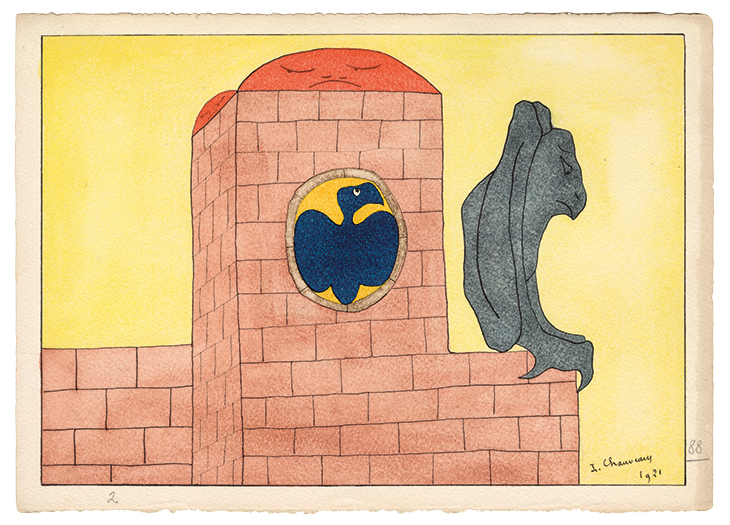

Drawing 43 from the Paysages Monstrueux (1921), Léopold Chauveau

No watcher is more familiar than the figure found in the final image of the Paysages monstrueux of 1921. Perched hulking and grey on the corner of a wall or tower, talons tight on the blocks beneath, it looks out meditatively over a landscape we cannot see. Though it is examined in its turn by the white eye of a bright blue eagle in a crest on the wall, and though the tower itself has eyes dozily shut against the sun, the hunched figure is definitively alone. It is unclear what anatomy might be revealed if it were to stretch out and stand up, but its silhouette is unmistakable. It is the archetype of the stone devil high on its tower, watching the world below.

The familiarity of the silhouette makes it hard to place exactly: like all archetypes, it seems too ever-present to have a traceable origin. But, despite the old iconography of devilry echoed in it, and the endless history of mankind’s general dealings with monsters, Chauveau’s watcher and the watchfulness of all its kin are symptoms of a distinctively modern kind of monstrosity. Like all monsters, the modern monster has an origin myth shrouded in shadows, but it emerges clearly into the light in the 19th century – less than 20 years before Chauveau’s birth – in the form of two plates by the Parisian etcher Charles Meryon: Le Stryge (‘The Vampire’, 1853) and Sur une Chimère de Notre Dame de Paris (‘On a Chimera from Notre-Dame de Paris’, 1853).

Le Stryge (1853), Charles Meryon. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New Yorkfig

Between them, the physical outline of Chauveau’s watcher is immediately recognisable: the knees that overtop its shoulders reprise the curve of the Stryge’s neatly folded wings; its staring hunch echoes the contracted huddle of the second plate’s ape. More than this, though, in the lineage that runs from Chauveau back to Meryon and beyond, it is the metaphysical outline of the modern monster that emerges: a creature, nervy and spectatorial, whose only option is to watch the world go by.

Meryon (1821–67) had his own reasons to obsess over monsters. The illegitimate child of an English doctor and a dancer at the Paris Opéra, he was unacknowledged by his father in his early years, and left largely alone in the world at 17 when his mother died, in the grip of mental illness. After years in the navy that, according to one biographer, culminated in him conceiving a phobia of the sea itself after witnessing a fellow seaman captured and cooked alive in the South Seas, he settled in Paris as an etcher. Despite meeting success and praise for the 22 prints of his Eaux-fortes sur Paris (1850–54), however, his grip on his sanity was tenuous. In Baudelaire’s words, ‘a cruel demon touched M. Meryon’s brain’. The mental illness that claimed his mother descended on him too, leading to internment at Charenton asylum. After his release, Meryon only got worse: he fell in love with a 13-year-old girl and he surrendered to his delusions even further – among them, the idea that he himself was a literal monster. As Baudelaire recorded in 1860, Meryon became convinced that he had ‘morally assassinated’ the girl and her mother, and that the woman-killing orangutan of Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘Murders in the Rue Morgue’ was none other than himself.

Self-portraits by proxy, the Chimère and the Stryge illustrate Meryon’s conviction that he was closer to ape than man, and as the verse he wrote below the Stryge suggests, that he was consumed by ‘the vampire, eternal lust’. As his conversation with Baudelaire showed, he believed acutely and painfully in his lack of fitness for human society. For a man who believed himself doomed, for the good of other people, to be alone, the company of other monsters provided a kind of fearful solace.

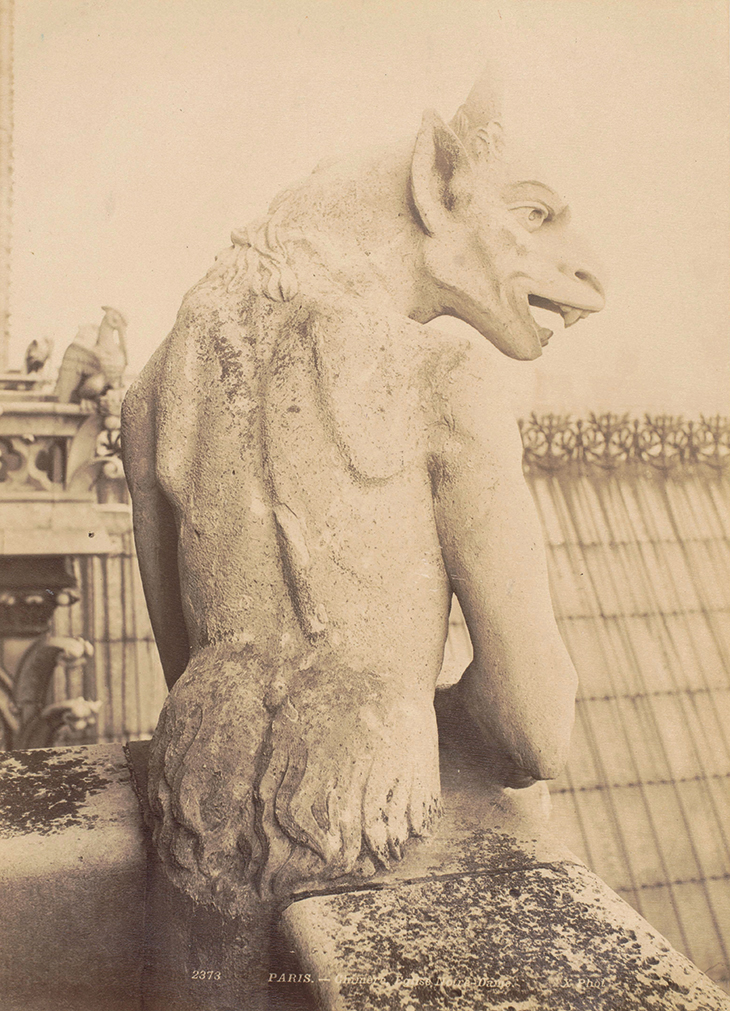

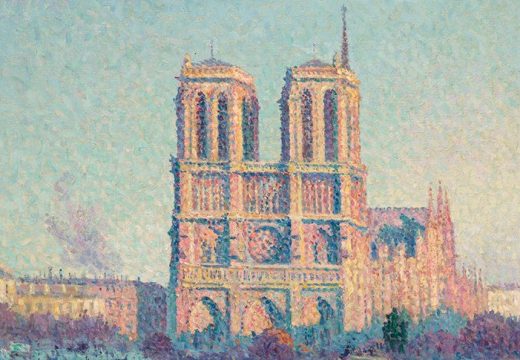

If Meryon’s reaction was extreme, in 19th-century Paris he was far from the only person to respond to the magnetic draw of monsters. As the title of Sur une Chimère suggests, Meryon drew his images from sculptures on Notre-Dame. Like so much of the cathedral that survived until the fire in 2019, these sculptures were children of the vast restoration project undertaken in 1843–64 by Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc and Jean-Baptiste Lassus. Individually designed by Viollet-le-Duc, and carved by the sculptor Victor Pyanet, they are not of an age with the old cathedral itself, but with the Paris of Daguerre, Haussmann and Baudelaire.

The attention that Viollet-le-Duc gave to his bêtes and gargoyles was remarkable. Gargoyles – named for the French gargouiller, ‘to gargle’ – are functional creatures designed to direct water from the roofs out away from the edifice below: they could be simple spouts. Viollet-le-Duc made sure that among the several hundred required by Notre-Dame’s elaborate restoration no two had identical features: each one was its own monster. Even more attention was given to the differentiation between the purely ornamental bêtes. Human in scale, perched on the ‘Grande Galerie’ of the facade, they combine animal and grotesque human elements with old and new iconographies of diablerie drawn from popular prints and religious art alike to create a set that is systematically incoherent. Each individual figure looks out in a different direction from the parapet: alone in each other’s company. The original of Meryon’s Stryge does not look out hungrily, but pensively: isolated in, and by, its gaze.

Bête on Notre-Dame, Paris, designed by Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc and sculpted by Victor Pyanet. Photograph: c. 1875–1900. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

That isolated gaze was partially a question of fashion. As Michael Camille observes, 1830s Paris ‘went demon-crazy’, heavily under the influence of gothic novels imported from England, German writers like E.T.A. Hoffmann, and homegrown Romantics like Victor Hugo. Devils were so omnipresent that Théophile Gautier complained in Le Figaro he could scarcely ‘read a novel, hear a play or listen to a story without being beset by mystical words, or angelic, diabolical, or cabalistic names’. The 19th-century devil was a creature who came of age as the city’s dark and winding medieval streets began to give way to the arcades, gardens, and boulevards of the modern, rationally designed city. An increasingly familiar and human figure, the devilish monster morphed from pure evil-doer into observer and onlooker, practically a Baudelairean flâneur. When Meryon’s Stryge entered the scene, encapsulating the shift, it quickly became one of the most reproduced prints of the century: the defining image of the modern monster.

Unlike the flâneur, though, the new monsters of the 19th century were not observers by choice. Their watchfulness comes about because, unlike their medieval forebears, the modern monster is distinguished by one thing above all: that he, as a monster, will always be alone. Medieval monsters, drawing on the richly fanciful heritage passed on by Pliny’s Natural History, were almost never alone. They were members of races that shared forms, homelands, and habits: the headless blemmyae of Libya, with faces in their bellies; the dog-headed cynocephali of India, barking out one word in every three; the skiapodes of Ethiopia, napping under the parasol of their one vast foot.

The modern monster, by contrast, might belong to a recognisable iconography, but he is, like Viollet-le-Duc’s bêtes, unique. His spiritual father is Victor Frankenstein’s creation, born in 1818 – nameless and companionless, his monstrosity and his loneliness inseparable. A monad set apart by visible monstrosity, that monster’s participation in any community is limited to skulking in a woodshed peering through a crack in the wall. ‘Everywhere,’ he tells Frankenstein, ‘I see bliss, from which I alone am irrevocably excluded.’ The choice the monster offers Frankenstein is to build an Eve to his Adam, or for his creator to see, one by one, all his own community murdered, until he too is exiled from mankind. ‘There can be no community between you and me,’ Frankenstein replies, ensuring their mutual doom.

Wrapped up with loneliness, the modern monster’s evil is no longer essential, but contingent. Like a child, he acquires it – if he acquires it at all – from the community that shuns him. ‘I was benevolent and good; misery made me a fiend,’ Frankenstein’s creation tells him. The unholy trinity of modern monsters that presides over the 19th century – Frankenstein’s fiend, Quasimodo, and Dracula – craves, above all else, the ability to integrate into human life. Quasimodo’s very name contains a hunger for love: it is taken from the opening words of the service for the Sunday on which he was found at Notre-Dame, quasi modo geniti infantes rationabile sine dolo lac concupiscite (‘Crave pure spiritual milk, like newborn babies’). Even Dracula, suavest and most evil of the three, is, at heart, an old bachelor who longs ‘to be in the midst of the whirl and rush of humanity, to share its life’, touchingly concerned in case someone hear his accent and proclaim, ‘Ha, ha! a stranger!’

The result, in the end, is that the modern monster is primed to lose his monstrosity. Precisely because so lonely, he is ready, always, to provide congenial company for beings who feel, like him, set apart from others. And few people are lonelier than children, for whom the paradoxical lure of the monstrous is particularly strong. Nowhere is this clearer than in Léopold Chauveau’s vast and long neglected body of work. The son of a respected veterinary and medical researcher in Lyon, Chauveau nursed an interest in monsters and art, but found himself forced into medicine at the behest of his father. ‘Even as a small child,’ he told an interviewer in the last year of his life, ‘monstrous things pleased me. I had only seen the gargoyles on a few cathedrals, some Chinese and Japanese monsters, and already I sensed that this was a world made for me.’

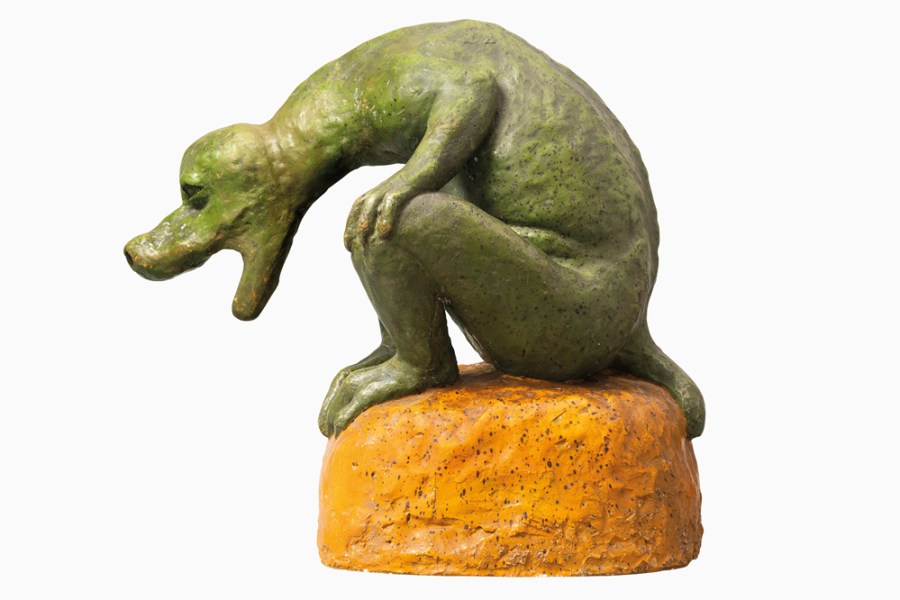

Monstre (Autoportrait?) (1908), Léopold Chauveau. Photo: © Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt

The direct influence of Meryon and Viollet-le-Duc is visible across the earliest of Chauveau’s sculptures, and nowhere more clearly than in the small Monstre (Autoportrait?) from 1908: demon-eared, hands clasped behind its back, looking out from beneath heavy brows that echo both Le Stryge and Chauveau’s own features, a mischievous smile on its lips. Chauveau’s output, though, remained slim until after the devastation of the First World War. He was called up as a doctor, and his traumatic experiences of treating the wounded and mutilated filled a short memoir, Derrière la bataille (1917), and left him feeling, according to his journal, that ‘all these dying children are the real adults compared to us, old and useless, who stay behind’. The worst losses were personal: his oldest son drowned in September 1915 aged 16, his best friend’s son was killed at the front in July 1918, and his wife died of grief and sickness later in the same year; that December, after Chauveau himself operated on him, his third son, Renaud, died of septicaemia. ‘I cannot even give myself the consolation that they died for something,’ Chauveau wrote in his journal nine days after Renaud’s death. ‘They died for nothing […] All they have done is added to the immense heap of the dead to tear me apart.’

The devastation of the 20th century’s wars would, of course, spur artists such as Picasso and Bacon to much darker visions of monstrosity, but for Chauveau monsters provided a welcome form of retreat. Abandoning medicine, he dedicated himself professionally to writing, and in private to his monsters. Friendly with literary figures such as André Malraux and André Gide as well as artists including Gauguin and Bonnard – who illustrated two of his books – he met success as a creator and illustrator of tales for children, populated by talking animals and absurdist personages. A flavour can be found in The Marvellous Cures of Doctor Popotame (1927), whose eponymous hero moves through his community of animals causing havoc with experimental treatments, including gluing the dead back together back-to-front before reviving them, and regrowing tails with essence of crayfish (which has the side effect of making the patient walk backwards). Eventually, he orchestrates a campaign to end white colonialism by using his patented noir popotame to dye any European who enters his territory black, and thus, in the book, make them friendly.

Tante Louise (c. 1911), Léopold Chauveau. Photo: © Musée d’Orsay/Patrice Schmidt

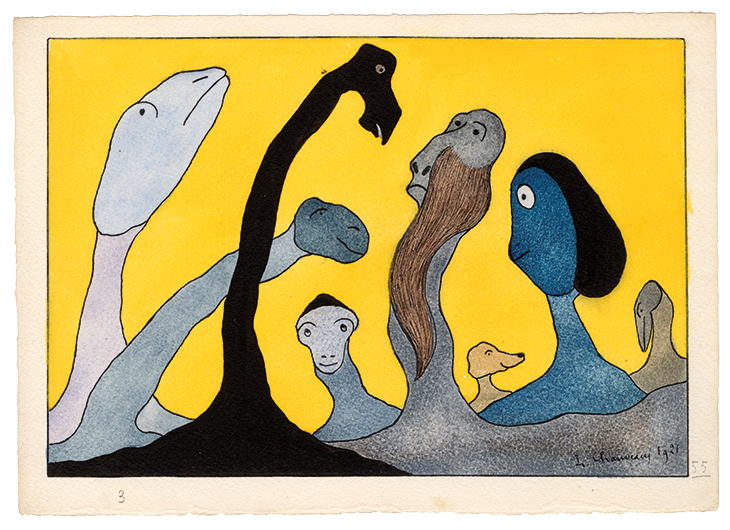

The fantasy of painting or sculpting the world into a kinder place is ever-present in Chauveau’s artistic output. Up to his death at the beginning of the Second World War, he created more than 50 sculptures in wax, plaster and bronze, and – including illustrations for his own books – some 500 watercolours, and more than 300 drawings. They are by no means all as lonely as the grey watcher he received from Meryon and Viollet-le-Duc, but they are that figure’s descendants. A glorious fantasia of organic, zoo- and anthropomorphic forms, his monsters all appear, quasi modo geniti infantes, as innocents in the world. Across the Paysages monstrueux, they range, stretch, and explore, often melancholy, searching, and just occasionally – as in the eighth drawing of the series from 1921 – finding the community that they so clearly crave. They were, too, a community of refuge for Chauveau himself: describing them in September 1939, he called them ‘very kind, very gentle, very harmless – very silly, next to the real live monsters who are turning the world upside down now’.

Drawing 8 from the Paysages Monstrueux (1921), Léopold Chauveau. Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Chauveau, little known outside France even in his own lifetime, is an obscure figure, but the modern monsters he drew are everywhere in children’s literature. Descendants of the beasts of Mary Shelley, Hugo, and Viollet-le-Duc, they rampage across countless books from Where the Wild Things Are to The Gruffalo: oddly innocent, even at their scariest, always on the lookout for companionship.

‘The Land of Monsters: Léopold Chauveau (1870–1940)’ is at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, until 13 September (exhibition dates extended).

From the April 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home