French history has been defined by its cathedrals, from the coronation of Henri IV at Chartres in 1594 to the desecration of Saint-Denis in 1793 and the bombardment of Reims in the First World War. But Notre-Dame de Paris occupies a special place on this list, not simply by dint of the Île-de-la-Cité’s location at the geographic and symbolic heart of France. Notre-Dame has functioned for centuries as a place of reconciliation, mediating between heaven and earth, the king and his subjects. Here, dissonant political traditions have struck a wary compromise. On the western towers, statues of Charlemagne and Saint Louis stand alongside Louis XIV and Napoleon. The outpouring of grief expressed in response to the fire of Monday evening arose from disbelief that a monument so deeply embedded in the national psyche could be suddenly threatened with erasure.

Nicolas Coustou’s Pietà on the altar inside the Notre-Dame de Paris, photographed on 16 April 2019. Photo: Ludovic Marin/AFP/Getty Images

Notre-Dame represents not solely a place of worship, although the open-air vigils performed each night before the battered structure attest to its continuing hold upon the faithful. From the moment that Henri IV kneeled to receive the mass, Notre-Dame served as the stage upon which the Bourbon monarchy asserted its right to rule. Its greatest ministers and military heroes – including Cardinal Mazarin and the Grand Condé – were laid to rest with baroque magnificence. The captured enemy standards were displayed as the spoils of war, and news of French victories was consecrated with a hearty Te Deum. In 1638, Louis XIII formally dedicated his kingdom to the Virgin Mary to whose favour he accredited the birth of a son. Sixty years later, that longed-for son – Louis Dieudonné, the Sun King – honoured this vow through lavish renovations of the church entrusted to Robert de Cotte. Monumental sculptures for the sanctuary were commissioned from Antoine Coysevox and Nicolas Coustou. A photograph of Coustou’s Pietà, her arms raised in supplication and bathed in the golden light of the cross, announced the news of Notre-Dame’s deliverance in various outlets this week.

As with so much else, the French Revolution did not interrupt this marriage of pageantry and piety, but rather redirected it. Te Deum services were soon enlisted to hail the achievements of the new regime, from the abolition of feudal privileges in August 1789 to the Declaration of the Rights of Man in December 1793 and the abolition of slavery in February 1794. It is true that Notre-Dame was briefly converted by the Jacobins into a Temple of Reason, and the statues that formed the so-called galérie des Rois on the western front were dismantled (and symbolically decapitated). But beyond the relatively cosmetic acts of vandalism, what mattered during the revolutionary decade is that the doors were never closed. Little by little, traditional worship was resumed, and Notre-Dame came to symbolise the accommodation of religion and civil society. Despite the creation of the Panthéon as a rival necropolis, and the anticlerical reforms of the late 19th century, Notre-Dame still offered its benediction to the presidents of the Republic, starting with the assassinated Sadi Carnot in 1894, and followed by Félix Faure (whose death was hardly saintly), Raymond Poincaré, Charles de Gaulle and, most recently, François Mitterand.

The Vampire (1853), Charles Meryon. From the album Eaux-Fortes sur Paris. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In the 19th century, a new identity for Notre-Dame was forged, independent of its political functions. In his novel of 1831 Victor Hugo evoked the towers’ black silhouette and stone-ribs, ‘stood out against the starlit sky like an enormous two-headed sphinx sitting in the midst of the town’. While he argued that the rise of printing had killed off the universal language of architecture – ‘ceci tuera cela’ – Hugo’s own text demonstrated the power of the literary imagination to unriddle the sphinx and recast the cathedral as an exuberant icon of liberty. This spirit of Romantic freedom animated the renovations undertaken after 1844 by Jean-Baptiste Lassus and Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, who laboured to improve on and complete the template handed down by the Middle Ages. As the late art historian Michael Camille explored, it was the rationalist, somewhat racist imagination of Viollet-le-Duc that invented the fantastic gargoyles or feline chimères that scowled down from the towers. Like Hugo, Viollet-le-Duc believed in the monstrous qualities of the gothic, which made the structure eerily animate; as a child, he had fled Notre-Dame in terror one day when he believed that one of its rose windows had started to sing and shriek.

Notre Dame, Paris. View of spire, roof with statuary, and cityscape beyond (c. 1860), Charles Marville. Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

The flames have been merciless towards Viollet-le-Duc’s renovations and additions, in which he fused the medieval with the modern. When Charles Marville photographed the new spire in 1861, he paid homage to a wonder of design and engineering. He also demonstrated the new optics of the cathedral whose towers afforded a panoramic view over the city below. As reinforced by the photographs of Henri le Secq and the prints of Charles Meryon, Parisians found in the gargoyles an emblem of their own fascinated and melancholy gaze on the city. Baron Haussmann’s brutal redevelopment of the Cité cut Notre-Dame off from its neighbourhood, replacing dense residential housing with drab administrative buildings. No longer a viable community church, Notre-Dame threw open doors to the world, symbolised by the vast open square (parvis), a focal point for pilgrims, protestors, tourists, and now mourners.

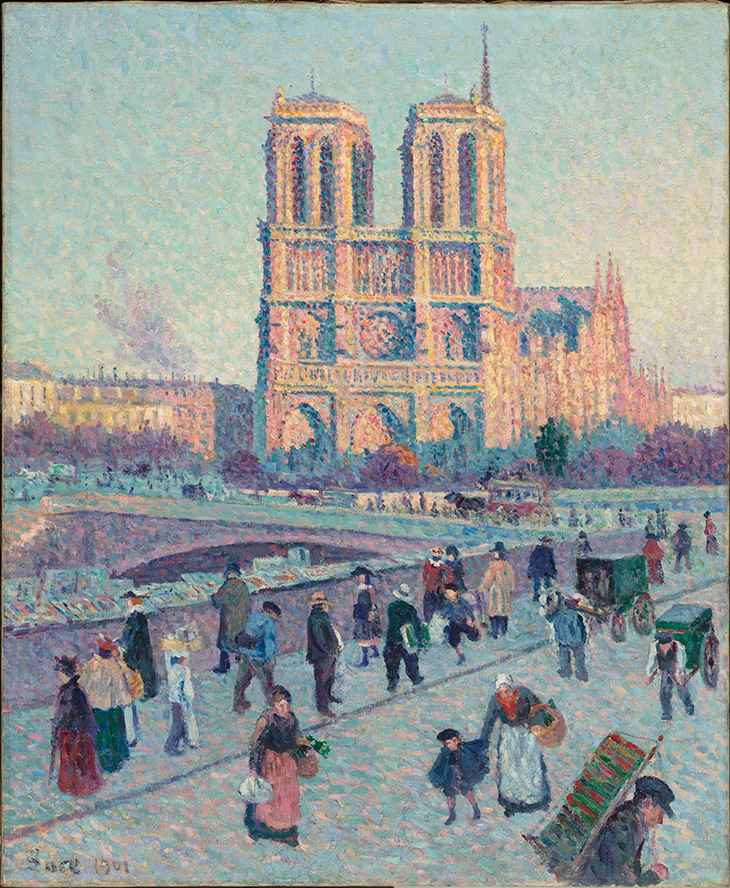

Le Quai Saint Michel et Notre-Dame de Paris (1901), Maximilien Luce. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo: © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d’Orsay)/Hervé Lewandowski

Artists played their role in celebrating Notre-Dame not just as a civic temple, but as an indispensable Parisian landmark. At the turn of the 20th century, the anarchist, neo-Impressionist painter Maximilien Luce explored Notre-Dame through 15 ‘series paintings’, capturing the shifting colours of the western façade at different times of day. His iridescent example was taken up by Albert Marquet, Matisse and even Picasso, who during the war could see the cathedral from his studio on rue des Grands Augustins. Notre-Dame emerged from months of street-fighting unscathed, and on 9 May 1945 the great bell (bourdon) sounded the note of liberation. In choosing to paint the cathedral that month, Picasso celebrated a building whose resilience emblematised that of the whole country. Even for this recently converted communist, Notre-Dame exemplified some idea of ‘eternal France’. Whether in triumph and adversity, its fortunes, as invoked by Emmanuel Macron on Monday night, have merged with the destiny of France itself.

Tom Stammers is a cultural historian of France in the long 19th century, and an assistant professor in the department of history at Durham University.

‘Notre-Dame’s fortunes have merged with the destiny of France itself’

Le Quai Saint Michel et Notre-Dame de Paris (detail; 1901), Maximilien Luce. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Photo: © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d'Orsay)/Hervé Lewandowski

Share

French history has been defined by its cathedrals, from the coronation of Henri IV at Chartres in 1594 to the desecration of Saint-Denis in 1793 and the bombardment of Reims in the First World War. But Notre-Dame de Paris occupies a special place on this list, not simply by dint of the Île-de-la-Cité’s location at the geographic and symbolic heart of France. Notre-Dame has functioned for centuries as a place of reconciliation, mediating between heaven and earth, the king and his subjects. Here, dissonant political traditions have struck a wary compromise. On the western towers, statues of Charlemagne and Saint Louis stand alongside Louis XIV and Napoleon. The outpouring of grief expressed in response to the fire of Monday evening arose from disbelief that a monument so deeply embedded in the national psyche could be suddenly threatened with erasure.

Nicolas Coustou’s Pietà on the altar inside the Notre-Dame de Paris, photographed on 16 April 2019. Photo: Ludovic Marin/AFP/Getty Images

Notre-Dame represents not solely a place of worship, although the open-air vigils performed each night before the battered structure attest to its continuing hold upon the faithful. From the moment that Henri IV kneeled to receive the mass, Notre-Dame served as the stage upon which the Bourbon monarchy asserted its right to rule. Its greatest ministers and military heroes – including Cardinal Mazarin and the Grand Condé – were laid to rest with baroque magnificence. The captured enemy standards were displayed as the spoils of war, and news of French victories was consecrated with a hearty Te Deum. In 1638, Louis XIII formally dedicated his kingdom to the Virgin Mary to whose favour he accredited the birth of a son. Sixty years later, that longed-for son – Louis Dieudonné, the Sun King – honoured this vow through lavish renovations of the church entrusted to Robert de Cotte. Monumental sculptures for the sanctuary were commissioned from Antoine Coysevox and Nicolas Coustou. A photograph of Coustou’s Pietà, her arms raised in supplication and bathed in the golden light of the cross, announced the news of Notre-Dame’s deliverance in various outlets this week.

As with so much else, the French Revolution did not interrupt this marriage of pageantry and piety, but rather redirected it. Te Deum services were soon enlisted to hail the achievements of the new regime, from the abolition of feudal privileges in August 1789 to the Declaration of the Rights of Man in December 1793 and the abolition of slavery in February 1794. It is true that Notre-Dame was briefly converted by the Jacobins into a Temple of Reason, and the statues that formed the so-called galérie des Rois on the western front were dismantled (and symbolically decapitated). But beyond the relatively cosmetic acts of vandalism, what mattered during the revolutionary decade is that the doors were never closed. Little by little, traditional worship was resumed, and Notre-Dame came to symbolise the accommodation of religion and civil society. Despite the creation of the Panthéon as a rival necropolis, and the anticlerical reforms of the late 19th century, Notre-Dame still offered its benediction to the presidents of the Republic, starting with the assassinated Sadi Carnot in 1894, and followed by Félix Faure (whose death was hardly saintly), Raymond Poincaré, Charles de Gaulle and, most recently, François Mitterand.

The Vampire (1853), Charles Meryon. From the album Eaux-Fortes sur Paris. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

In the 19th century, a new identity for Notre-Dame was forged, independent of its political functions. In his novel of 1831 Victor Hugo evoked the towers’ black silhouette and stone-ribs, ‘stood out against the starlit sky like an enormous two-headed sphinx sitting in the midst of the town’. While he argued that the rise of printing had killed off the universal language of architecture – ‘ceci tuera cela’ – Hugo’s own text demonstrated the power of the literary imagination to unriddle the sphinx and recast the cathedral as an exuberant icon of liberty. This spirit of Romantic freedom animated the renovations undertaken after 1844 by Jean-Baptiste Lassus and Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, who laboured to improve on and complete the template handed down by the Middle Ages. As the late art historian Michael Camille explored, it was the rationalist, somewhat racist imagination of Viollet-le-Duc that invented the fantastic gargoyles or feline chimères that scowled down from the towers. Like Hugo, Viollet-le-Duc believed in the monstrous qualities of the gothic, which made the structure eerily animate; as a child, he had fled Notre-Dame in terror one day when he believed that one of its rose windows had started to sing and shriek.

Notre Dame, Paris. View of spire, roof with statuary, and cityscape beyond (c. 1860), Charles Marville. Library of Congress, Washington D.C.

The flames have been merciless towards Viollet-le-Duc’s renovations and additions, in which he fused the medieval with the modern. When Charles Marville photographed the new spire in 1861, he paid homage to a wonder of design and engineering. He also demonstrated the new optics of the cathedral whose towers afforded a panoramic view over the city below. As reinforced by the photographs of Henri le Secq and the prints of Charles Meryon, Parisians found in the gargoyles an emblem of their own fascinated and melancholy gaze on the city. Baron Haussmann’s brutal redevelopment of the Cité cut Notre-Dame off from its neighbourhood, replacing dense residential housing with drab administrative buildings. No longer a viable community church, Notre-Dame threw open doors to the world, symbolised by the vast open square (parvis), a focal point for pilgrims, protestors, tourists, and now mourners.

Le Quai Saint Michel et Notre-Dame de Paris (1901), Maximilien Luce. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. Photo: © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d’Orsay)/Hervé Lewandowski

Artists played their role in celebrating Notre-Dame not just as a civic temple, but as an indispensable Parisian landmark. At the turn of the 20th century, the anarchist, neo-Impressionist painter Maximilien Luce explored Notre-Dame through 15 ‘series paintings’, capturing the shifting colours of the western façade at different times of day. His iridescent example was taken up by Albert Marquet, Matisse and even Picasso, who during the war could see the cathedral from his studio on rue des Grands Augustins. Notre-Dame emerged from months of street-fighting unscathed, and on 9 May 1945 the great bell (bourdon) sounded the note of liberation. In choosing to paint the cathedral that month, Picasso celebrated a building whose resilience emblematised that of the whole country. Even for this recently converted communist, Notre-Dame exemplified some idea of ‘eternal France’. Whether in triumph and adversity, its fortunes, as invoked by Emmanuel Macron on Monday night, have merged with the destiny of France itself.

Tom Stammers is a cultural historian of France in the long 19th century, and an assistant professor in the department of history at Durham University.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

An elegy for Notre-Dame, in words and pictures

The great Gothic cathedral has inspired innumerable artists and writers over the centuries

Competition to design Notre-Dame spire announced

Art news daily: 17 April

Efforts to salvage art from Notre-Dame continue as Macron vows to rebuild

Art news daily: 16 April