After the fire, the debate has begun over how Paris’s great cathedral should be rebuilt: should it be restored as it was 100 years ago, or 500? Or should architects attempt something radical and fresh?

Paul Binski

Many of us would agree that Notre-Dame should be reconstructed, and that what shouldn’t happen is that the task becomes hijacked by politicians. President Macron’s promise to get the work done within five years, in time for the 2024 Olympics, has provoked a calm but firm response from 1,169 international signatories to a letter in Le Figaro to the effect that he should at least allow us to take time. But for what? Time, certainly, to consider the true extent of the fire and water damage to the building, to the spectacular vaulting system and the glass. As I watched the (in its way) sublime spectacle of the fire on TV, my hope was that the building would do its job – the stone vaults acting as a bulwark against the timber roof on fire over them. I wasn’t relaxed, but oddly confident. Such vaults were engineered in castles in the medieval Anglo-Norman domain, where fire hazards were great. And so it turned out: Notre-Dame worked well, as far as we know at the moment, because it was from the start a clever building. No miracles were involved, just cunning.

And, of course, imagination. Begun around 1160, Notre-Dame was the first ‘high-rise’ gothic church, exceeding even the monstrously big Romanesque abbey church at Cluny in Burgundy. Its vaults rose to well over 30 metres. Within a century it was provided with new transepts, whose grand façades, with portals, spiky gables and rose windows, were cited throughout Europe. In the 15th century, masons at other French churches were still being sent to Notre-Dame to see one of the canonical study points for gothic architecture.

Reconstructing it ‘faithfully’ could entail a number of agendas. It has been well said that Notre-Dame was always a work in progress. No sooner had the high walls gone up than they were overshadowed by the dazzling tall clerestories of Chartres, and duly upgraded. The church was adapted well into the 14th century, rededicated after 1789 to revolutionary ‘Reason’, and then remodelled in a spirit of modern archaeological enquiry. Daguerreotypes of the church around 1840 show no spire – though the medieval one is shown in the fabulous view of Paris as ‘Jerusalem’ in the Très Riches Heures of Jean, Duc de Berry, of around 1415. Much of what went up in smoke in April was the work of Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, a 19th-century harbinger of modernity as well as a prodigious scholar. The church’s look has changed in marginal ways often enough. By maintaining the work in progress, we could claim to be acting faithfully in the spirit of medieval gothic.

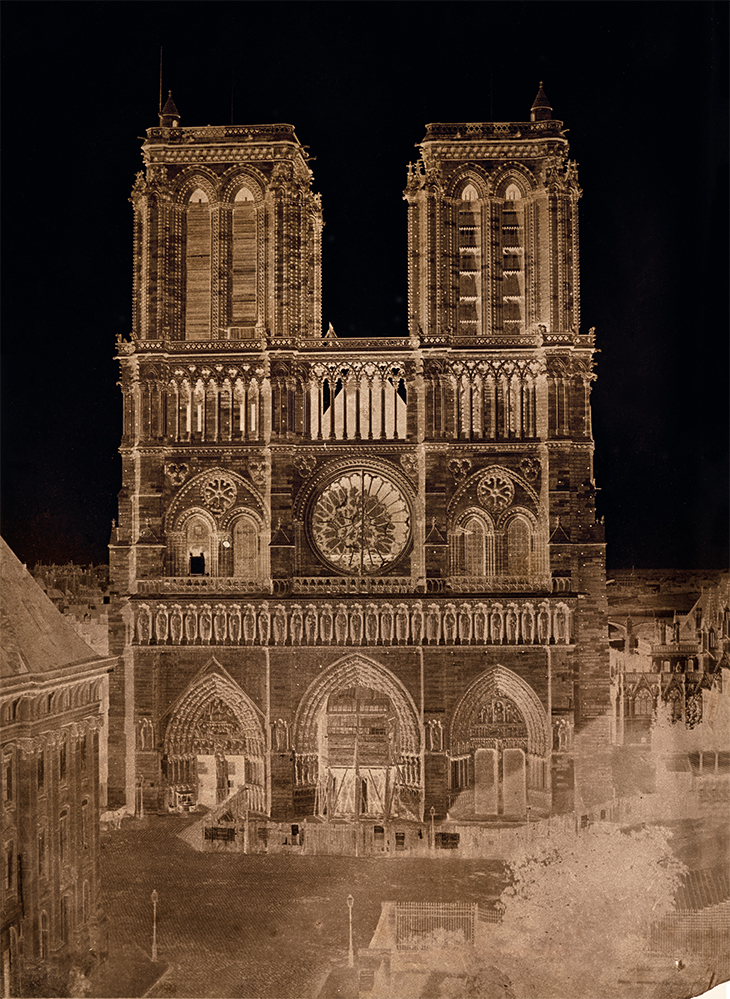

Notre-Dame, Paris (c. 1853), Charles Nègre. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

But is there real scope for rewarding departure now? The lofty vaults will have been damaged by fire and will need replacing wholly or partly, yet gothic buildings are so seamless and integrated that replacing these huge, oversailing canopies of stone with something new would probably not work either visually or structurally. That leaves the spire put up in the middle years of the 19th century. When it comes to the familiar, a special sort of courage is needed, for intervention can easily come to look like iconoclasm. The onus of proof is shifted on to those who would want to do something brand new.

Putting Notre-Dame ‘back’ wouldn’t necessarily be some Humpty-Dumpty act of affectionate mummification, but rather an act of basic respect for the accomplishment and heritage of a radical building. In recent years, some architectural historians have even spoken of medieval gothic as a form of modernism, and though the analogy is overstated, the sense of structural and imaginative radicalism it captures illuminates this building and what it stands for. Notre-Dame is part of the more general narrative of modernism; it contributed to our world as well as to the medieval one, to the idea that architecture can be, as Jean Bony said, a form of ‘visionary engineering’. Much of our debate stems, after all, from different Romanticisms and their conflicting outcomes – the romance of the new, the romance of the old, and the romance of the ‘faithful’: for authenticity and sincerity are themselves ideas of the 19th century, the period that produced the still popular view, inspired by Victor Hugo, of Notre-Dame as a monument to a certain sort of feeling.

Paul Binski teaches medieval art at the University of Cambridge. His latest book, Gothic Sculpture, has just been published by the Paul Mellon Centre with Yale University Press.

Douglas Murphy

It was, of course, a great relief when it became clear that the fire in the roof of Notre-Dame de Paris was not going to bring the whole thing crashing to the ground, and that the stone vaults had for the most part isolated the rest of the building from the flames. But this relief was tempered by a sense of trepidation, over the inevitably ensuing round of the ‘What are we to do with the damaged monument?’ debate.

I had previously been infuriated by the gall of certain figures in Scottish contemporary architecture suggesting that the fire-gutted Glasgow School of Art be fitted with a newly designed interior, to be decided by competition. This was an open-and-shut case – the singularity and rarity of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s vision undoubtedly necessitates a facsimile rebuild – but the syncretic nature of gothic cathedral architecture meant that the opportunists would have a much stronger case.

Sure enough, within two days the French government had announced an international competition seeking a replacement for the spire, the collapse of which, taking the vault above the crossing down with it, provided the most shocking image from the fire. Prime Minister Édouard Philippe said that the new design could be ‘adapted to the techniques and the challenges of the era’, and over the following days and weeks the architectural press filled with proposals and suggestions.

Plenty of these were simple provocations: designer Mathieu Lehanneur imagined a structure in the form of the flames themselves, while historian Tom Wilkinson, writing in Domus, made the modest proposal of adding a minaret, predictably raising the ire of the online far-right in the process. The public interest in the story means there is a rare opportunity for architects and designers to reach an audience far exceeding their normal ‘impact’, and so anyone with access to Photoshop and five minutes to spare was able to contribute on social media.

Other suggestions were less outlandish, with a common theme being reconstructions that would take the form of the previous roof and spire, but would be made from steel and glass. Some established architects made their interest known: Massimiliano and Doriana Fuksas suggested a new roof made of Baccarat crystal, while Norman Foster expressed a desire to enter the competition, also suggesting a glass roof above the original.

That Foster would want to be involved is telling: he is one of the great representatives of a tendency within architecture to emphasise the technological aspects of construction. Born in 1935, he was one of the pioneers of British ‘High Tech’ – an approach that combined utopian space-age aesthetics with the tradition of 19th-century engineer-geniuses, and eventually became the style of choice for millennial technocracy. High Tech took less influence from the order and decorum of classical architecture, or the concrete cubism of late modernism, and looked more to gothic, with its unruliness, its joyous expression of structure, and the apparent pragmatism of its peripatetic master masons.

In defending the opportunity to build anew, Foster speaks of a ‘tradition of new interventions’ in gothic cathedrals. This harks right back to their pan-generational construction periods, but also indirectly refers to the refurbishments and classicising that went on over the years. The rhetoric also largely leans on the history of ‘restoration’, since during the 19th century the crumbling cathedrals were repaired, but in the process were transformed into confections of themselves. In the case of Notre-Dame this was performed by Viollet-le-Duc, whose replacement spire, we are often reminded, is a confabulation of what gothic architecture genuinely was.

It helps the reconstructor’s case that Viollet-le-Duc himself was, in his writings and teachings, an advocate of new styles of building derived from the combination of gothic tectonics and innovations in iron and glass technology. His ambitious but clunky perspectives have the quality of old illustrations of the future of flying machines, but help make the rhetorical leap from flying buttresses in stone all the way to the steel and glass of today’s proposals. Much depends on the unfolding of the politics of the repair work, but like it or not, those advocating something new for Notre-Dame are at least being consistent.

Douglas Murphy’s most recent book is Nincompoopolis: The Follies of Boris Johnson (Repeater Books).

From the June 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Should Notre-Dame be reconstructed faithfully?

Illustration by Graham Roumieu/Dutch Uncle

Share

After the fire, the debate has begun over how Paris’s great cathedral should be rebuilt: should it be restored as it was 100 years ago, or 500? Or should architects attempt something radical and fresh?

Paul Binski

Many of us would agree that Notre-Dame should be reconstructed, and that what shouldn’t happen is that the task becomes hijacked by politicians. President Macron’s promise to get the work done within five years, in time for the 2024 Olympics, has provoked a calm but firm response from 1,169 international signatories to a letter in Le Figaro to the effect that he should at least allow us to take time. But for what? Time, certainly, to consider the true extent of the fire and water damage to the building, to the spectacular vaulting system and the glass. As I watched the (in its way) sublime spectacle of the fire on TV, my hope was that the building would do its job – the stone vaults acting as a bulwark against the timber roof on fire over them. I wasn’t relaxed, but oddly confident. Such vaults were engineered in castles in the medieval Anglo-Norman domain, where fire hazards were great. And so it turned out: Notre-Dame worked well, as far as we know at the moment, because it was from the start a clever building. No miracles were involved, just cunning.

And, of course, imagination. Begun around 1160, Notre-Dame was the first ‘high-rise’ gothic church, exceeding even the monstrously big Romanesque abbey church at Cluny in Burgundy. Its vaults rose to well over 30 metres. Within a century it was provided with new transepts, whose grand façades, with portals, spiky gables and rose windows, were cited throughout Europe. In the 15th century, masons at other French churches were still being sent to Notre-Dame to see one of the canonical study points for gothic architecture.

Reconstructing it ‘faithfully’ could entail a number of agendas. It has been well said that Notre-Dame was always a work in progress. No sooner had the high walls gone up than they were overshadowed by the dazzling tall clerestories of Chartres, and duly upgraded. The church was adapted well into the 14th century, rededicated after 1789 to revolutionary ‘Reason’, and then remodelled in a spirit of modern archaeological enquiry. Daguerreotypes of the church around 1840 show no spire – though the medieval one is shown in the fabulous view of Paris as ‘Jerusalem’ in the Très Riches Heures of Jean, Duc de Berry, of around 1415. Much of what went up in smoke in April was the work of Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, a 19th-century harbinger of modernity as well as a prodigious scholar. The church’s look has changed in marginal ways often enough. By maintaining the work in progress, we could claim to be acting faithfully in the spirit of medieval gothic.

Notre-Dame, Paris (c. 1853), Charles Nègre. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

But is there real scope for rewarding departure now? The lofty vaults will have been damaged by fire and will need replacing wholly or partly, yet gothic buildings are so seamless and integrated that replacing these huge, oversailing canopies of stone with something new would probably not work either visually or structurally. That leaves the spire put up in the middle years of the 19th century. When it comes to the familiar, a special sort of courage is needed, for intervention can easily come to look like iconoclasm. The onus of proof is shifted on to those who would want to do something brand new.

Putting Notre-Dame ‘back’ wouldn’t necessarily be some Humpty-Dumpty act of affectionate mummification, but rather an act of basic respect for the accomplishment and heritage of a radical building. In recent years, some architectural historians have even spoken of medieval gothic as a form of modernism, and though the analogy is overstated, the sense of structural and imaginative radicalism it captures illuminates this building and what it stands for. Notre-Dame is part of the more general narrative of modernism; it contributed to our world as well as to the medieval one, to the idea that architecture can be, as Jean Bony said, a form of ‘visionary engineering’. Much of our debate stems, after all, from different Romanticisms and their conflicting outcomes – the romance of the new, the romance of the old, and the romance of the ‘faithful’: for authenticity and sincerity are themselves ideas of the 19th century, the period that produced the still popular view, inspired by Victor Hugo, of Notre-Dame as a monument to a certain sort of feeling.

Paul Binski teaches medieval art at the University of Cambridge. His latest book, Gothic Sculpture, has just been published by the Paul Mellon Centre with Yale University Press.

Douglas Murphy

It was, of course, a great relief when it became clear that the fire in the roof of Notre-Dame de Paris was not going to bring the whole thing crashing to the ground, and that the stone vaults had for the most part isolated the rest of the building from the flames. But this relief was tempered by a sense of trepidation, over the inevitably ensuing round of the ‘What are we to do with the damaged monument?’ debate.

I had previously been infuriated by the gall of certain figures in Scottish contemporary architecture suggesting that the fire-gutted Glasgow School of Art be fitted with a newly designed interior, to be decided by competition. This was an open-and-shut case – the singularity and rarity of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s vision undoubtedly necessitates a facsimile rebuild – but the syncretic nature of gothic cathedral architecture meant that the opportunists would have a much stronger case.

Sure enough, within two days the French government had announced an international competition seeking a replacement for the spire, the collapse of which, taking the vault above the crossing down with it, provided the most shocking image from the fire. Prime Minister Édouard Philippe said that the new design could be ‘adapted to the techniques and the challenges of the era’, and over the following days and weeks the architectural press filled with proposals and suggestions.

Plenty of these were simple provocations: designer Mathieu Lehanneur imagined a structure in the form of the flames themselves, while historian Tom Wilkinson, writing in Domus, made the modest proposal of adding a minaret, predictably raising the ire of the online far-right in the process. The public interest in the story means there is a rare opportunity for architects and designers to reach an audience far exceeding their normal ‘impact’, and so anyone with access to Photoshop and five minutes to spare was able to contribute on social media.

Other suggestions were less outlandish, with a common theme being reconstructions that would take the form of the previous roof and spire, but would be made from steel and glass. Some established architects made their interest known: Massimiliano and Doriana Fuksas suggested a new roof made of Baccarat crystal, while Norman Foster expressed a desire to enter the competition, also suggesting a glass roof above the original.

That Foster would want to be involved is telling: he is one of the great representatives of a tendency within architecture to emphasise the technological aspects of construction. Born in 1935, he was one of the pioneers of British ‘High Tech’ – an approach that combined utopian space-age aesthetics with the tradition of 19th-century engineer-geniuses, and eventually became the style of choice for millennial technocracy. High Tech took less influence from the order and decorum of classical architecture, or the concrete cubism of late modernism, and looked more to gothic, with its unruliness, its joyous expression of structure, and the apparent pragmatism of its peripatetic master masons.

In defending the opportunity to build anew, Foster speaks of a ‘tradition of new interventions’ in gothic cathedrals. This harks right back to their pan-generational construction periods, but also indirectly refers to the refurbishments and classicising that went on over the years. The rhetoric also largely leans on the history of ‘restoration’, since during the 19th century the crumbling cathedrals were repaired, but in the process were transformed into confections of themselves. In the case of Notre-Dame this was performed by Viollet-le-Duc, whose replacement spire, we are often reminded, is a confabulation of what gothic architecture genuinely was.

It helps the reconstructor’s case that Viollet-le-Duc himself was, in his writings and teachings, an advocate of new styles of building derived from the combination of gothic tectonics and innovations in iron and glass technology. His ambitious but clunky perspectives have the quality of old illustrations of the future of flying machines, but help make the rhetorical leap from flying buttresses in stone all the way to the steel and glass of today’s proposals. Much depends on the unfolding of the politics of the repair work, but like it or not, those advocating something new for Notre-Dame are at least being consistent.

Douglas Murphy’s most recent book is Nincompoopolis: The Follies of Boris Johnson (Repeater Books).

From the June 2019 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

‘Notre-Dame’s fortunes have merged with the destiny of France itself’

Over the centuries Notre-Dame de Paris has become much more than a place of worship – it is a symbol of a nation

An elegy for Notre-Dame, in words and pictures

The great Gothic cathedral has inspired innumerable artists and writers over the centuries

‘The building as it was is gone for good’ – remembering the Glasgow School of Art

The devastating fire at the Glasgow School of Art means that incredibly difficult decisions lie ahead