Our bodies are never quite our own. The American artist Christina Ramberg (1946–1995) saw how the female form in particular has become a screen on to which the fears and fantasies of our culture are projected. In ‘The Making of Husbands’, Ramberg’s paintings are featured alongside work by a generation of younger artists who have similarly disassembled the theatre of gender.

Ramberg began exhibiting her work in the late ’60s, when second-wave feminism and the sexual revolution were galvanising middle-class America. In her Black Widow (1971), we see the classic image of the femme fatale: a woman in lace bodice and black knickers, tiny waist emphasising her curves. It mimics the kind of image cut from a lingerie magazine: seductive and obelisk-smooth. The figure’s head is chopped off, her identity obscured. (Ramberg spoke of watching her mother dressing up, ‘transforming herself into the kind of body men want. I thought it was fascinating […] In some ways, I thought it was awful’.) Probed Cinch, another acrylic-on-Masonite painting from the same year, zooms in further: a similarly headless torso, corseted with an hourglass waist. Blood-red fingernails complement a shock of auburn hair. It’s a trope of femininity endlessly recycled by Hollywood and the beauty industry: artificial, mute, almost mythical. Alongside these images, Sara Deraedt’s Nilco (2009) – a photograph of an abandoned vacuum cleaner – draws out the connection between the kinked, voluptuous geometry of this household object and the way in which domestic work is traditionally coded as ‘feminine’.

Willful Excess (1977), Christina Ramberg. Courtesy Collection of Karin Tappendorf; © the Estate of Christina Ramberg

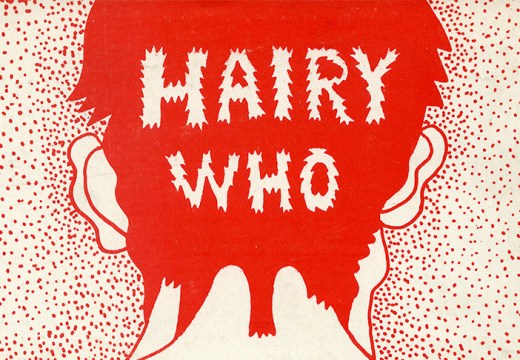

The centrepiece of the show is Ramberg’s series of Surrealist-inspired paintings from the mid ’70s. The works look both vividly modern – stamped with the cartoonish flair of the Chicago Imagists, whom Ramberg ran with – and almost ethnographic, like ancient totems carved from wood. In Tight Hipped (1974), the torso is flattened and painted with hard, unwavering lines, rendering its strange proportions – broad shoulders, lithe waist, bulging crotch – curiously sexless. Strips of shiny, black lacquered hair decorate the hips, wrists and shoulders, like eccentric details on an androgynous costume. In Willful Excess (1977), the body is depersonalised even further: it could be a sewing pattern or a clothes hanger, the curved lines suggesting flesh before transforming into a more rigid, grid-like silhouette. By 10 Watt Night Table Lamp (from the same year), the corporeal has been discarded completely: the strands of hair that form the base of the lamp resemble snarled and rusted pieces of metal.

Installation view of ‘The Making of Husbands: Christina Ramberg in Dialogue’ at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, 2020. Pictured is Senga Nengudi’s R.S.V.P Reverie “Scribe” (2014). Photo: Rob Harris © 2020 BALTIC

Is beauty inherently cruel? Senga Nengudi’s R.S.V.P Reverie “Scribe” (2014) gives three-dimensional form to Ramberg’s contortions and visual seductions. Echoing Sarah Lucas’s witty, satirical skewerings of sex, the piece features stuffed nylon tights weighted to resemble arachnid-like legs, pieces of metal dangling from the crotch with lewd suggestiveness. Alexandra Bircken’s assemblages carry a similarly eerie erotic charge. In the German sculptor’s Löwenmaul (2017), long, wavy strands of black hair are sewn on to a bra and pinned to the wall in unnerving disarray, while INXS (2016) features a headless leather-clad mannequin, peroxide-blonde hair fringing the shoulders. Again, the line between masculine and feminine, human and non-human, is blurred.

Elsewhere, Ghislaine Leung’s installations of found objects explore the idea of gendered space. In Violets (2018), a series of steel ventilation pipes invoke the cold, masculine impersonality of urban infrastructure, punctured by a quaint ‘Welcome’ sign in ornate wrought iron (with bell). A work by Frieda Toranzo Jaeger takes that most macho of human-machine hybrids, the car, and undercuts its usual significations. Her installation’s fold-out screens are decorated with colourful braids, wheels painted with slapdash, childlike strokes. The slumped drivers are either dead or asleep – adrenaline replaced by boredom.

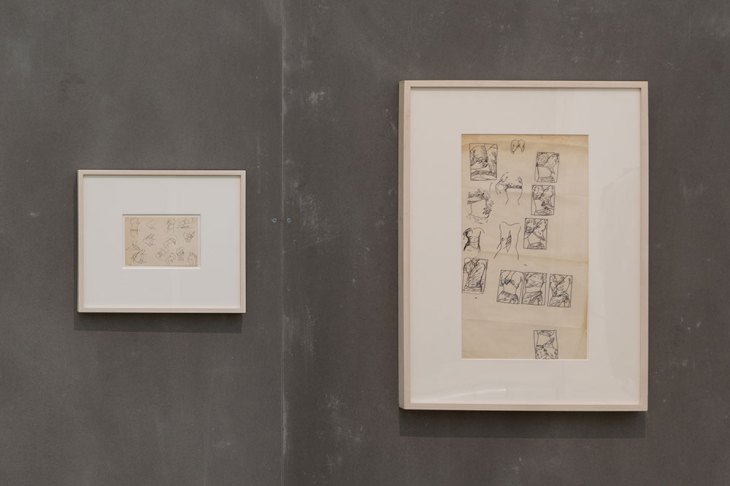

Installation view of ‘The Making of Husbands: Christina Ramberg in Dialogue’ at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, 2020. Photo: Rob Harris © 2020 BALTIC

The exhibition shows how Ramberg’s work served as a blueprint for these more recent investigations. The show culminates with a series of her untitled drawings, taken from her notebooks from the early ’70s onwards. From obsessive renderings of brutal-looking corsets and plaited hairstyles to a ‘How to build a woman’-esque catalogue of paper doll clothes, these works reveal an imagination bound by little other than the bluntly gendered reality of having a body.

‘The Making of Husbands: Christina Ramberg in Dialogue’ is at BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, until 21 February 2021.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home