From the February 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Christopher Wren, who died 300 years ago this month, is England’s most famous architect – the only one whose face has graced a banknote. Yet he remains an enigmatic figure, whose legacy continues to be contested by architectural historians. Some have seen him as a great scientist-architect – an English equivalent of Claude Perrault – who realised the triple dome of St Paul’s Cathedral with its cubic-parabolic core. To others, he is the bridesmaid of the English baroque: the designer of monumental palaces and royal hospitals that, though impressive, don’t go quite as far in terms of sheer invention as the buildings of his pupils Nicholas Hawksmoor and John Vanbrugh. There’s also Wren the theoretician, his library full of copies of Vitruvius. For Lisa Jardine in her biography of 2002, Wren was a political agent, a Tory Royalist on a mission to obscure the memory of the Interregnum behind walls of white Portland stone. Recently, he has been cast by Vaughan Hart as the purveyor of architectural wisdom from the ancient Near East, Byzantium, and the Ottomans – an architect of almost radical eclecticism.

If Wren’s approach to architecture is hard to pin down, his personality remains even more mysterious. His own letters and his appearances in contemporary diaries suggest detachment to the point of cold-bloodedness – this is certainly the Wren depicted by Peter Ackroyd in his novel Hawksmoor (1985). Yet Wren’s contemporaries also write affectionately of his warmth as a friend, his honour and, above all, his trustworthiness.

Christopher Wren (c. 1690), John Closterman. Royal Society, London

We can glimpse something of the man from his correspondence, of which Anthony Geraghty and I are currently preparing a scholarly edition. One letter, in particular, sums up how Wren saw his personal and architectural achievements. In April 1719, towards the end of his long life, Wren wrote a letter to his former paymasters, the Lords of the Treasury. Reflecting on his 50-year career, he told the Lords that he had ‘worn out (by God’s Mercy) a long life in Royal Service’, adding that it was because of this service that he had ultimately ‘made some figure in the world’. Looking back then, Wren saw his life as one defined principally by ‘Service’. To be sure, his was a life of near-constant service to institutions: the Crown, the Church and, to a lesser extent, the universities of Oxford and Cambridge. This is reflected in his architectural out-put: very few buildings designed by Wren were not for one of these four clients.

Wren held four official positions over the course of his career: one for the Crown and three for the Church. The most important was that of Surveyor of His Majesty’s Works, based in the Office of Works in Scotland Yard, Whitehall. He was appointed to this role in 1669 and he held it until 1718. It was in this capacity that Wren oversaw and administered all royal building work including the major new extension to Hampton Court Palace and the two royal hospitals at Chelsea and Greenwich.

Alongside his royal duties, he headed another office, responsible for the designing and building of the City Churches after the Great Fire. This was based in the same space as the Office of Works and involved many of the same personnel, but it was administratively distinct. He was also Surveyor to the Fabrics of the two principal Anglican buildings of London: St Paul’s (from 1669) and Westminster Abbey (from 1698). Duties to the former occupied him on-and-off for nearly half a century and resulted in his most famous building, the rebuilt cathedral.

St Paul’s Cathedral, London, rebuilt to designs by Christopher Wren in 1675–1710. Photo: Grant Smith/View Pictures/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Wren’s work for the universities of Oxford and Cambridge fell outside of the purview of these offices and was facilitated by his friendships with college heads and divines. Yet it was resolutely institutional rather than private in any way. It involved the occasional consultation for the City of London (another institution) and its Livery Companies, rare one-off projects such as the Drury Lane Theatre and a handful of small-scale domestic designs. It is telling that the one major residential commission that did land on Wren’s desk – for a new house at Easton Neston in Northamptonshire for William Fermor, 1st Baron Leominster – was delegated to his pupil Hawksmoor.

So it seems that the notion of service to one’s Church and country, a pursuit deemed noble for members of the 17th-century English gentry, was fundamental to how Wren understood his approach to architecture – but what does that tell us about the resulting buildings? The answer here lies in his sources. Influences on Wren’s architecture can be broken down into three broad categories: contemporary French, antiquity and everything else (which includes contemporary Dutch, 16th-century Italian, Byzantine and other Eastern sources). Wren’s use of sources from all three of these categories was shaped by his awareness of himself as a civil servant.

The Old Royal Naval College, Greenwich, designed by Christopher Wren and built in 1696–1712. Photo: James Brittain/View Pictures/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

As Elizabeth Deans has shown in her ongoing research on Wren’s early career, his visit to Paris in the summer of 1665 (the only time he left England) was formative. While in the French capital, he met with all of Louis XIV’s court architects and, crucially, he witnessed the French royal building works in action. This operation was overseen by the greatest administrator of 17th-century Europe, Jean-Baptiste Colbert – a figure whose influence on Wren has not previously been noted. As Deans suggests, Wren modelled the running of his subsequent offices on Colbert’s ministry – a hyper-regulated bureaucracy that produced highly trained draughtsmen, surveyors and architects to ensure that huge commissions were finished on schedule and within budget. Wren would rarely succeed in these last respects, but he certainly tried. After 1665, he also based his personal drawing style on the graphic techniques of French court architects such as Louis Le Vau – and trained his draughtsmen to do the same. That so many of Wren’s designs are clearly influenced by French architecture of this period comes as no surprise. The dome and west portal of St Paul’s, Greenwich Hospital and Hampton Court are the most obvious indications of Wren’s Francophilia. But I would argue that they reflect his deep admiration not for French architectural taste, but for French government bureaucracy.

Hampton Court Palace, designed by Christopher Wren and built 1689–1700

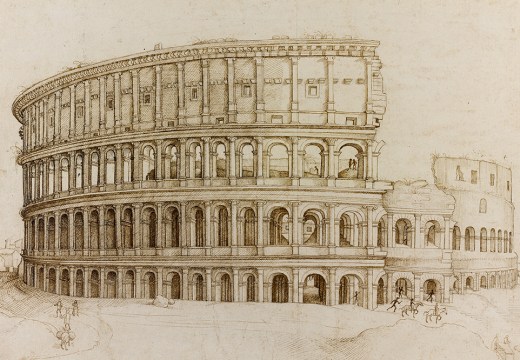

As is clear in his ‘Tracts’, Wren considered the ancient Greeks and Romans to be the greatest architects who ever lived. This was, of course, an entirely standard position for architectural theorists of the late 17th and early 18th centuries – but Wren, again, was interested above all in the ways in which classical architecture was completed in the service of the great institutions of the ancient world. He was fascinated by the writings of Vitruvius, even if he didn’t always agree with him. As Vitruvius makes clear throughout De Architectura, he saw himself, like Wren, as first and foremost a servant of the principal building-generating institution of his own day: the Roman state under the emperor Augustus. Wren may very well have modelled his own service to the English Crown on Vitruvius’s dedication to that prototypical architectural patron, the ruler who claimed to have transformed Rome into a city of marble in the same way that Wren and his contemporaries hoped to create a new London out of Portland stone. Likewise, the specific ancient buildings that Wren singled out for praise in his writings were large-scale imperial or regal projects, invariably commissioned by the major patron-builders of antiquity: the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, the Artemision at Ephesus as rebuilt under Alexander the Great, the Temple of Mars Ultor erected by Augustus in Rome, and Vespasian’s Templum Pacis (which Wren, like all his contemporaries, mistook for the later and better preserved Basilica of Maxentius). For Wren, these were examples of civic magnificence, built by architects in service to the dynastic monarchies of the Hellenistic period and the later Roman Imperial state.

Wren was undeniably eclectic in his influences. He borrowed Byzantine squinch dome construction (for St Stephen Walbrook and St Paul’s), 16th-century Italian church and villa planning (in the early designs for the cathedral and elsewhere) and 17th-century Dutch church spires (in a great many of the City Church towers). But Wren’s range of sources was a means to an end, rather than part of some deeper commitment to eclecticism. He was a pragmatist, looking to use whatever means he could to create appropriate splendour without incurring prohibitive difficulty or expense. When Wren was charged with replacing the spires that dominated the London skyline prior to 1666, he recognised the need for vertical structures that were magnificent in appearance, but quick and affordable to produce. Earlier in the century, Dutch architects – particularly Hendrick de Keyser – had proved that classical architectural language could be reconciled with medieval spires, balancing orders, scrolls, obelisks and other features placed on top of one another to create impressive focal points in an urban landscape. Wren borrowed the trick out of convenience. In doing so, he created designs as memorable as the towers of St Mary-le-Bow and St Bride’s, Fleet Street.

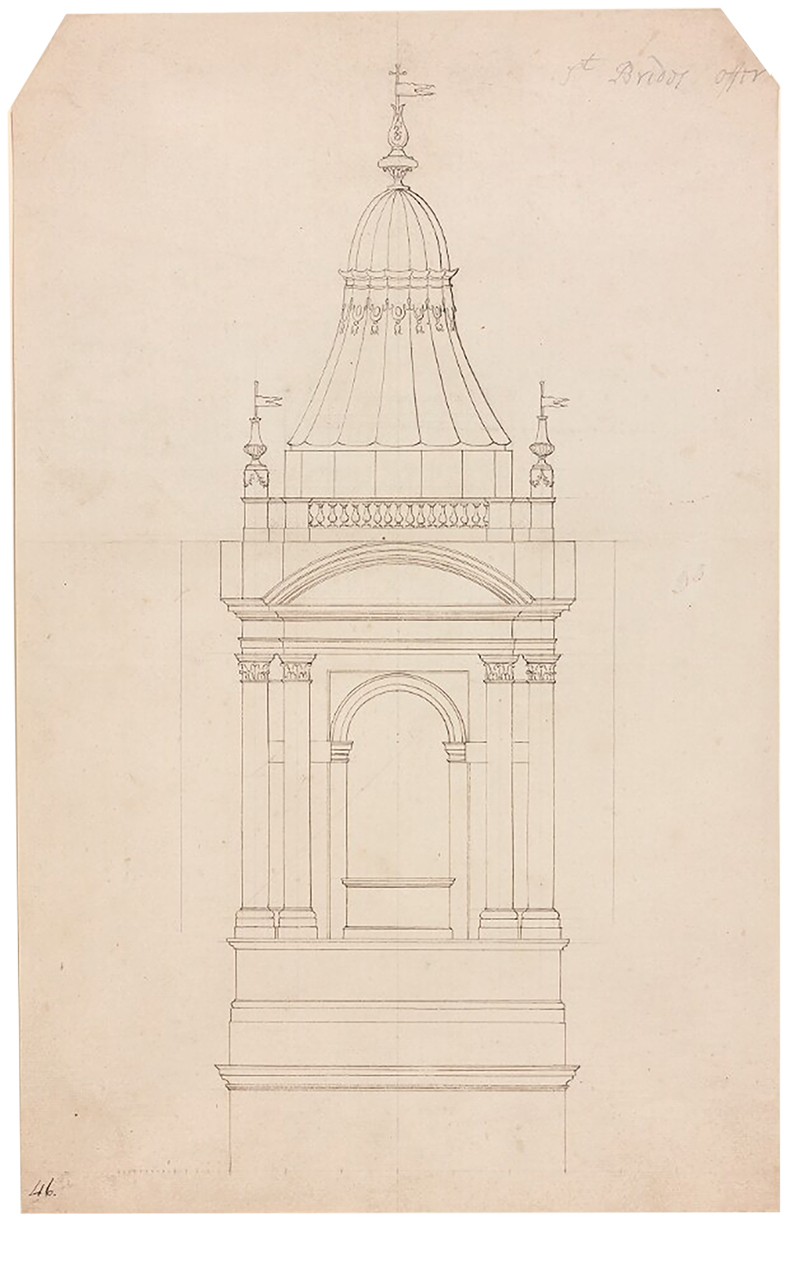

Drawing for the tower of St Bride’s, Fleet Street (c. 1675–76), Christopher Wren. All Souls College, Oxford

Once again, the goal was service – to the Church of England and its parishes and to the magnificence of the nation’s capital and its skyline. For Wren, the office mattered more than his own architectural allegiances. In this respect, there is something quasi-professional – in an age before architectural professionalism – about his career. Had he been born 300 years later, I suspect he would have worked quite happily for the London County Council architects’ office or sat on a Diocesan Advisory Committee. But thinking of Wren as someone who valued institutional service above everything else is by no means to do him down – in fact, it allows for all the other readings of him. He could be scientific, baroque, antiquarian, political and eclectic all at once, because the office came first. He was adaptable, rather than ideological. He was, first and foremost, what he said he was: the most loyal of servants to the Anglican Church and to the English Crown.

Sir Christopher Wren (1711), Godfrey Kneller. National Portrait Gallery, London

From the February 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home