Ciaran Carson’s final volume of poetry, Still Life, published last month, just after he passed away, ends with the lines: ‘And I loved the big windows and whatever I could see through them, be it cloudy or clear, / And the way they trembled and thrilled to the sound of the world beyond.’

The book is structured as a series of responses to paintings – by Old Masters, modern painters and contemporary Irish artists – opening out on to wider reflections. The transformative joy that comes from seeing the world in all its complexity is at the centre of Ciaran’s writing, with those framing windows always there, in the forms his poetry took, its rhythms and textual patterns, as the shapes of that looking and understanding.

Ciaran Carson was a poet, translator, novelist, musician, and teacher. His native Belfast, which gave him the imaginative geography of much of his writing, was, for Ciaran, a bilingual city, first experienced in his childhood in Irish and then in English, and then, in his later years, filtered through the various languages he translated from. Ciaran’s debut volume of poetry, The New Estate, was published in 1976, but it was The Irish for No (1987) and Belfast Confetti (1989), with their long lines and intense engagement with the particularities of the city, which established him as a singular poetic chronicler of Belfast’s streets, history, conflict, and its urban textures. He reinvented his poetry continually throughout his career, turning, for example, to extraordinarily taut, syntactically crystalline poems in short lines in later volumes such as On the Night Watch (2009) and Until Before After (2010). In each volume some overriding rhythmic presence asserts itself – the thump-thump of British Army helicopters over Belfast, the spin cycle of a washing machine, the melodies of traditional music.

His prose writings include Shamrock Tea (published in 2001 and longlisted for the Booker Prize), a novel of sorts in which the hallucinogenic tea is accessed by passing through and into Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait, and the glorious reflection on a Belfast childhood that is The Star Factory (1997), a playful, digressive, but always controlled version of a memoir which perambulates through the city via the way the city is remembered. Arriving in Belfast the night before Ciaran’s funeral I found myself thinking that the city had lost its voice and I realised the extent to which, for me and for many of his readers, his writing had given a weight and dignity to Belfast’s psychogeographies.

I was lucky enough to work with Ciaran on several occasions, but it was in his role as a translator that, slightly by chance, I worked most closely with him and saw his writing actually happen. Ciaran was a translator of extraordinary virtuosity. The Inferno of Dante Alighieri (2002) is one of his most magnificent achievements. Written in the aftermath of the Good Friday Agreement, it consciously stitches its place of translation – early 21st-century Belfast – into its text, while also standing alone as a version of Dante’s poem in its own right. His translation of the ancient Irish epic poem The Táin (2007) is equally brilliant.

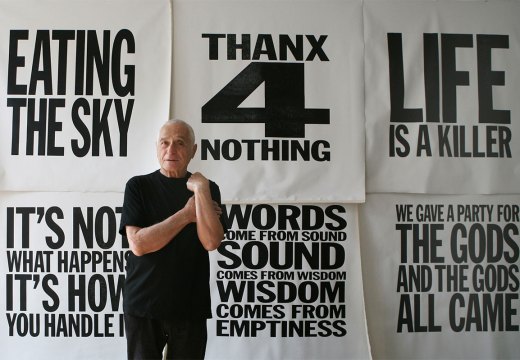

Ciaran Carson at the exhibition ‘In the Light Of’ at Illuminations, Maynooth University, in 2012. Photo: Paul Kay

Ciaran had also translated Mallarmé, Rimbaud and Baudelaire, or at least made wonderful ‘versions’ of their poetry, in The Alexandrine Plan (1998), so when I set up a digital art gallery (showing artwork only on TV screens) in 2012 and named it ‘Illuminations’, I thought that my ideal first commission would be to ask Ciaran to translate seven of the prose poems in Rimbaud’s strange book Illuminations and to ask graphic designers — those contemporary versions of manuscript illuminators — to illustrate the poems. He replied to the email I sent the same day to say he’d tried doing these translations before and had never been able to do it, and in any case he hadn’t been writing much of anything recently. The poems in Rimbaud’s book stretch logic and the coherence of image and syntax, so I could see why they be unlikely to be attractive as a venture. That was fine, I said, but I added that I thought he could do a better job than John Ashbery, who had published a full translation of Illuminations the year before.

The next morning in my inbox was a message from Ciaran including a translation of one of Rimbaud’s prose poems. Ciaran had solved his Illuminations problem by translating the poems’ forms as well as their language — his versions turned Rimbaud’s into verse poems, reverting to the alexandrines the French poet had used before and allowing his surrealism to shine through this imposition of partial order. And over the next few weeks Ciaran sent me translations daily, well in excess of the seven I’d asked for, so that he eventually translated the entire book. In the Light Of (2012) was published to coincide with the opening of the Illuminations gallery. Those two weeks, seeing Ciaran’s work appear on a daily basis in my inbox, as he created these astonishing poems, were one of the great privileges of my working life.

Having worked for many years as Traditional Arts Officer at the Arts Council of Northern Ireland, Ciaran was later appointed Professor and Director of the Seamus Heaney Centre at Queen’s University Belfast, and there he fostered a vibrant and supportive environment for a new generation of poets from Ireland and beyond. One of his great legacies will be in the writing he made possible by the kindness and integrity of his mentorship of young writers. But it is as the writer of some of the best poetry of the last few decades, in any language and from any place, that Ciaran Carson will be remembered. He was a writer of depth and virtuosity. He was a translator in the widest and most profound sense — he allowed other texts to live in and through his own words, his own curiosity, his own times and places, his own passions.

The series of ekphrastic poems that make up Still Life, his final book, written knowing it would be his final book, tenderly interweave his life in Belfast with paintings he admired – the landscapes of Poussin, for example – and his own viewing of those landscapes, in galleries, in books, via pixellated screen versions. The penultimate poem in the collection, ‘Yves Klein, IKB, 1959’, begins with the sound of an explosion in a quarry outside Belfast and ends, devastatingly, with the only lines in the book that vary from the long, overlapping structure in every poem, as they recall the bombs of Bloody Friday in Belfast in July 1972. In the midst of these memories is the figure of Yves Klein, making his own blues, and then, in Leap into the Void, ‘soaring into space […] / […] his arms flung outward / In a theatrical facsimile of flight’. And that is Ciaran, thinking about his own coming leap into the void, much as he had, in earlier poems, imagined stepping through the ‘portals’ of Rothko paintings. It is Ciaran taking flight in the ‘quotidian beauty’ of an ordinary city street, just like the one Klein apparently flies over, because that is, among many other things, what his writing did — it made a city in need of being wondered at feel like it had a voice that could speak of its wonders. We are poorer, so much poorer, for the silencing of Ciaran Carson’s voice.

Colin Graham is Professor of English and Dean of the Faculty of Arts, Celtic Studies, and Philosophy at Maynooth University, Ireland.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home