You have to be seeking out the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exquisite show ‘Seeing the Divine: Pahari Painting of North India’ to find it, climbing two flights of stairs hidden in a corner of its Asian art galleries. The reward is an intimate encounter with 20 small paintings hung on the four walls of a single gallery, centred on a spectacular eight-metre-long embroidered banner wrapped around four sides of a display cabinet. The exhibition is just the right size for visitors to involve themselves in the very particular visual, psychological and emotional intensity of looking at the paintings.

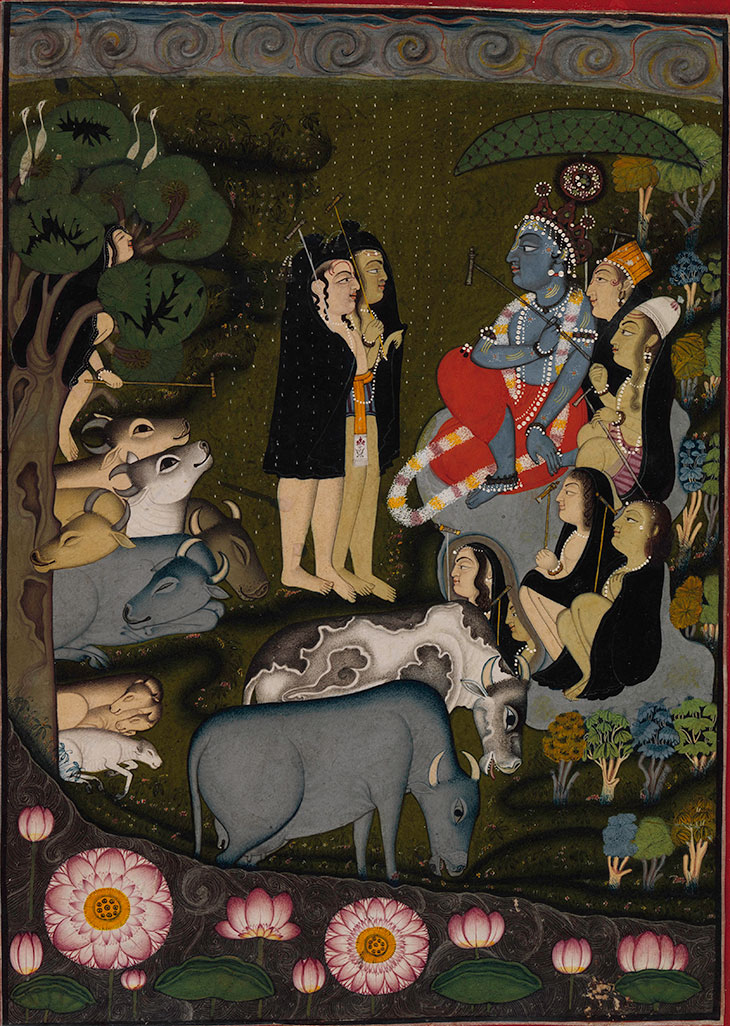

Krishna and the Gopas (Cowherders) Celebrate the Start of the Rainy Season (c. 1725–50), folio from a dispersed Bhagavata Purana, attributed to the Master of the Swirling Skies

The show’s inspiration is the substantial promised gift of Steven Kossak, made in 2015, of some 100 works of Indian art – among them, a distinguished concentration of north Indian paintings made at the Pahari courts, in the foothills of the Himalayas, during the 17th and 18th centuries. As the show’s curator Kurt Behrendt says, ‘With a small show you can tease out a single idea – representing the gods, in this case – and show it to the public’. Viewers witness how Pahari court painters devised fresh iconography to depict the Hindu gods within emotionally charged episodes from religious texts, encouraging the viewer to experience a personal and even passionate connection with the divine, an experience called bhakti.

Thus, around 1725–50 a painter working at the Jammu court, known as the Master of the Swirling Skies, composed an image of the god Krishna celebrating the start of the rainy season. In the text of the devotional Bhagavata Purana, the following line describes this episode: ‘The dried-up earth was fully replenished like the sensually motivated body of a repentant person’. The densely packed composition introduces a suggestive twilight atmosphere, some blossoming lotuses in the flowing river and cows looking adoringly at Krishna. The mesmerised viewer is lured into their own bhakti worship of Krishna.

Devi in the Form of Bhadrakali Adored by the Gods (c. 1660–70), folio from a dispersed Tantric Devi series, attributed to the Master of the Early Rasamanjari

Another painting, saturated in colour, portrays Bhadrakali, the Blessed Dark Goddess, a fearsome form of the goddess Devi whom many Hindus consider the most supreme deity, and who was especially popular in this region. It was one of some 70 images from a Tantric Devi series probably made for a royal devotee at the Basohli court around 1660–70. On the back of the folio, written in Sanskrit, are some verses:

Equal to a thousand rays of the rising sun…

She is everything…

She banishes fear…

I adore goddess Bhadrakali…

Again, the painter has returned to the text to create an innovative and animated visualisation: the goddess’s nimbus radiates across the saffron background; she is laden with jewellery, some crafted from cut beetle wings to catch the light. The composition is packed with complex Devi iconography to show her at her most powerful. Again, the viewer who willingly submits is seduced into a passionate bhakti experience.

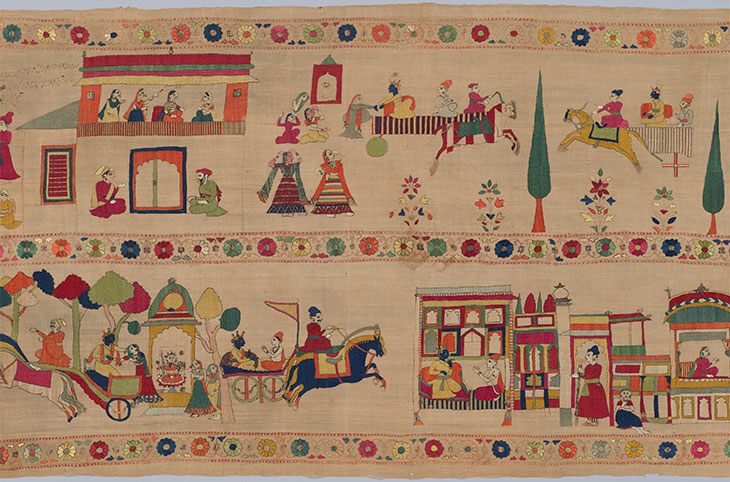

Festival Banner Showing Krishna Rescuing and Marrying Rukmini (detail; c. 1800), India, Punjab Hills, kingdom of Chamba

The banner offers some relief from the intensity of the paintings. Here is a lively silk embroidery on cotton ground that is in near-pristine condition. Worked in bright vegetable dyes made from safflower, cochineal, lac and indigo, plus metal-wrapped thread, it has all signs of being an expensive royal commission. In a continuous narrative running along two rows it recounts the story of Krishna rescuing – or perhaps abducting – Rukmini from the villainous Shishupala and marrying her, a morality tale of good triumphing over evil. The annual festival celebrating Krishna’s marriage to Rukmini is still celebrated in the Pahari hills today. This banner, made around 1800 at the Chamba court, may well have been intended to be a visual aid for storytellers, yet its condition shows it was barely used. It came to the Met in 1959 in a job lot of textiles, then languished in storage until the preparation for the museum’s new Islamic galleries, opened in 2012, which included having a good look at everything in the department of Asian art. Now it goes on public display for the first time.

‘Seeing the Divine: Pahari Painting of North India’ is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, until 21 July.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?