Last month, the J. Paul Getty Trust announced that images of around 4,600 artworks from their collection would be available to download free of charge and without restrictions. The initiative brings the Getty in line with several major American museums, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington and the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. James Cuno, President and CEO of the Getty Trust, stated that ‘understanding art makes the world a better place, and sharing our digital resources is the natural extension of that belief’. Noble sentiments indeed, but perhaps generosity comes easy to the world’s wealthiest art institution.

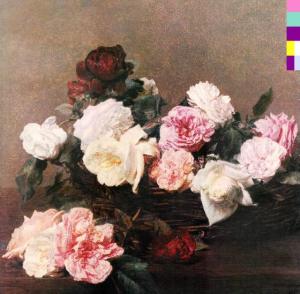

Power, Corruption & Lies (1983), New Order cover art.

In Britain, things tend to be a little less charitable. In 1983, the founder of Factory Records, Tony Wilson, reportedly telephoned Sir Michael Levey, then Director of the National Gallery, wanting to know why his request to reproduce Henri Fantin-Latour’s A Basket of Roses (1890) on the cover of the New Order album, Power, Corruption & Lies (1983) had been refused. When told by Sir Levey that the painting belonged to the people of Britain, Wilson is said to have responded ‘I believe the people want it’, at which point the director agreed to make an exception.

Despite this precedent most British museums continue to charge for digital reproductions according to intended use. Xavier Bray, Chief Curator at Dulwich Picture Gallery in London, states that ‘as an independent charity, not in receipt of regular government funding, it provides us with a small but necessary revenue’.

The justification is simple. Why should others profit from a museum’s assets? Potential revenue shortfalls in the coming years could not only render British museums effectively impotent on the international art market, but could even threaten essential daily operations. Commercial licensing is therefore a necessary evil, which helps to ensure that public art remains physically cared for and free to view.

However, as someone who has conducted commercial picture research, the systems currently in place can seem inefficient and overpriced. Guaranteeing that artworks are reproduced to highest quality is one thing, but insisting on multiple proofs over a period of weeks is quite another. In any case, if the artwork is publicly owned, why should we pay for what is already ours?

Le Découragement de l’artiste (The Discouraged Artist) (1895). A completely free Henri Fantin-Latour from the Getty. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

According to the 1988 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, the duration of copyright for any artistic work is 70 years from the end of the calendar year in which the last remaining author of the work dies. It would seem then that most Old Masters are currently in the public domain. However, it could even be argued that modern and contemporary art should also be available for reproduction free of charge. The ‘fair dealing’ clause of the same law permits, to a certain degree, the reproduction of artworks for the purposes of criticism and news reporting.

If only it were that simple. In practice, even if an artwork is technically in the public domain, access to high-quality photographs of that work might be additionally restricted, and a secondary form of fee essentially replaces any expired copyright pertaining to the original.

In 2009 the National Portrait Gallery began legal proceedings against Wikimedia Commons due to the alleged use of NPG images on their website. The gallery maintains that although the artworks are out of copyright, digital reproductions of the collection remain protected. This seems fair enough, after all digitisation projects are both costly and time-consuming. The issue was eventually resolved amicably and the museum provided 53,000 low-resolution images of their collection under a Creative Commons license, essentially ensuring against any commercial use.

Nurturing this kind of mutually beneficial relationship seems like a sensible way forward. However, in the future should a museum find themselves flush with cash, I hope they will remember Tony Wilson’s words and take a leaf out of the Getty’s book. Xavier Bray certainly sees the potential in providing open access. ‘I consider such a project to be a great marketing opportunity. Unfortunately, one needs the capital to be able to afford such a luxury.’

Getty’s Images

Le Découragement de l'artiste (The Discouraged Artist) Le Découragement de l'artiste (The Discouraged Artist ) Digital image courtesy of the Getty's Open Content Program.

Share

Last month, the J. Paul Getty Trust announced that images of around 4,600 artworks from their collection would be available to download free of charge and without restrictions. The initiative brings the Getty in line with several major American museums, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington and the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. James Cuno, President and CEO of the Getty Trust, stated that ‘understanding art makes the world a better place, and sharing our digital resources is the natural extension of that belief’. Noble sentiments indeed, but perhaps generosity comes easy to the world’s wealthiest art institution.

Power, Corruption & Lies (1983), New Order cover art.

In Britain, things tend to be a little less charitable. In 1983, the founder of Factory Records, Tony Wilson, reportedly telephoned Sir Michael Levey, then Director of the National Gallery, wanting to know why his request to reproduce Henri Fantin-Latour’s A Basket of Roses (1890) on the cover of the New Order album, Power, Corruption & Lies (1983) had been refused. When told by Sir Levey that the painting belonged to the people of Britain, Wilson is said to have responded ‘I believe the people want it’, at which point the director agreed to make an exception.

Despite this precedent most British museums continue to charge for digital reproductions according to intended use. Xavier Bray, Chief Curator at Dulwich Picture Gallery in London, states that ‘as an independent charity, not in receipt of regular government funding, it provides us with a small but necessary revenue’.

The justification is simple. Why should others profit from a museum’s assets? Potential revenue shortfalls in the coming years could not only render British museums effectively impotent on the international art market, but could even threaten essential daily operations. Commercial licensing is therefore a necessary evil, which helps to ensure that public art remains physically cared for and free to view.

However, as someone who has conducted commercial picture research, the systems currently in place can seem inefficient and overpriced. Guaranteeing that artworks are reproduced to highest quality is one thing, but insisting on multiple proofs over a period of weeks is quite another. In any case, if the artwork is publicly owned, why should we pay for what is already ours?

Le Découragement de l’artiste (The Discouraged Artist) (1895). A completely free Henri Fantin-Latour from the Getty. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

According to the 1988 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, the duration of copyright for any artistic work is 70 years from the end of the calendar year in which the last remaining author of the work dies. It would seem then that most Old Masters are currently in the public domain. However, it could even be argued that modern and contemporary art should also be available for reproduction free of charge. The ‘fair dealing’ clause of the same law permits, to a certain degree, the reproduction of artworks for the purposes of criticism and news reporting.

If only it were that simple. In practice, even if an artwork is technically in the public domain, access to high-quality photographs of that work might be additionally restricted, and a secondary form of fee essentially replaces any expired copyright pertaining to the original.

In 2009 the National Portrait Gallery began legal proceedings against Wikimedia Commons due to the alleged use of NPG images on their website. The gallery maintains that although the artworks are out of copyright, digital reproductions of the collection remain protected. This seems fair enough, after all digitisation projects are both costly and time-consuming. The issue was eventually resolved amicably and the museum provided 53,000 low-resolution images of their collection under a Creative Commons license, essentially ensuring against any commercial use.

Nurturing this kind of mutually beneficial relationship seems like a sensible way forward. However, in the future should a museum find themselves flush with cash, I hope they will remember Tony Wilson’s words and take a leaf out of the Getty’s book. Xavier Bray certainly sees the potential in providing open access. ‘I consider such a project to be a great marketing opportunity. Unfortunately, one needs the capital to be able to afford such a luxury.’

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

Share

Recommended for you

The Gallerists

Arthur Hobhouse and Patrick Barstow of New Artists (NA) abandon the gallery in favour of a smallpox-ridden catacomb

Misadventures

‘Les aventures de la vérité’ is a good opportunity squandered at the hands of Bernard-Henri Lévy

First Look: Canterbury and St Albans

Kristen Collins and Jeffrey Weaver introduce an exhibition of English Romanesque art which opens at the Getty on Friday