It is one of the curiosities of the Romantic movement that while Italy and its culture proved irresistible to so many major European artists the Italians themselves barely appear in the story. The peninsula features heavily in the work of a swathe of foreign painters, from Turner and Géricault to the Nazarenes and Delacroix, and its history and literature can be found in the works of everyone from John Martin and Thomas Cole to William Blake and Henry Fuseli. While there were great Italian Romantics such as Vincenzo Bellini, Niccolò Paganini and Giuseppe Manzoni, they made their mark in music and literature rather than the visual arts.

Just what was happening in art in Italy in the first 50 years of the 19th century is the subject of ‘Romanticismo’, a major exhibition held jointly at the Gallerie d’Italia and the Museo Poldi Pezzoli – institutions a mere hundred metres apart in the centre of Milan. The show features some 200 paintings and sculptures from the collection of 20,000 works (including Caravaggio’s final painting, The Martyrdom of St Ursula) owned by the Intesa Sanpaolo bank, which it displays in its galleries in Milan, Vicenza and Naples. ‘Romanticismo’ includes a handful of works by foreigners to give the wider perspective – among them Caspar David Friedrich’s Moon Rising Over the Sea (1821) from the Hermitage, a little Corot of the Roman campagna (1826) from the National Gallery in London, and Turner’s Lake Avernus: Aeneas and the Cumaean Sibyl (c. 1814–15), from New Haven – but almost everything else is Italian.

What emerges is both a host of unfamiliar names and a form of Romanticism that is more lyrical than elsewhere in Europe, one where fantasy and the mystical are less prevalent but reality and the human dimension more so. There is little Sturm und Drang or Turneresque atmospherics, hardly any Goya-like treatments of either the supernatural or extreme violence, and the bravura painterliness of Delacroix is nowhere to be found. Meanwhile, the French Revolution and the Napoleonic adventure, such a driving force elsewhere, barely leave a trace. And the Italians came late to the movement, some 15 years after its first stirrings elsewhere in the very early years of the 19th century.

Count Ugolino in the Tower (c. 1831), Giuseppe Diotti. Museo Civico Ala Ponzone, Cremona

If one painting can be said to encapsulate the difference represented by Italian Romanticism it is Giuseppe Diotti’s Count Ugolino in the Tower (c. 1831), an image based on the widely circulated print after Fuseli’s 1806 painting of the same theme. Fuseli concentrates on the figure of the tormented count, imprisoned and left to rot with his sons: his stare is manic, one son dies on his lap and the old man faces the choice of starvation or eating his own offspring. Diotti, however, turns the drama into an elegant composition: his count lacks the intensity of Fuseli’s agonised soul, while his four sons expire in attitudes of decorous beauty around him, all serpentine curves and droops. A year later, Diotti went further and enhanced this gentility with a second version of the painting, now in Brescia. In it he increases the colouring of the doomed family’s clothing so that this scene of horror is played out in beautifully rendered silk and velvet doublets and hose of orange, blue, burgundy and gold. What should be macabre has become a decorous salon painting.

There were, however, moments when Italy’s artists were more attracted to the sublime than the beautiful. One of the revelations of the exhibition is the work of Giuseppe Pietro Bagetti (1764–1831), a military engineer and architect but also a watercolourist with a bravura technique. His Ascent to Moncenisio (c. 1809), for example, is composed entirely in shades of khaki and grey and shows the tiny figures of men and laden mules climbing up the snowfields and mist of the mountain pass. The grandeur and power of the Alps and the smallness and impotency of man are perfectly captured and echo the works of John Robert Cozens and Caspar Wolf.

When he descended from the crags Bagetti was capable of the beautiful, too. Two of his watercolours of 1820–30 show the effect of the moon on clouds over the sea. While they clearly have their roots in direct observation, he gives the cloud formations a solidity that more resembles ectoplasm than nature and have an otherworldliness recalling Ingres’s The Dream of Ossian (1813). His was a distinctive vision.

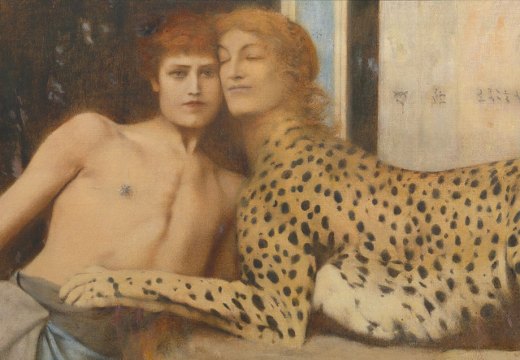

Meditation (1851), Francesco Hayez. Galleria d’Arte Moderna ‘Achille Forti’, Verona

The most recognisable painter on show is Francesco Hayez (1791–1882), whose The Kiss is the poster image for the Pinacoteca di Brera. He was a painter who mirrored Ingres in both the suavity of his technique and the range of his subjects, encompassing literature, portraiture, history painting, nudes and allegory. The highlight in the exhibition is his Meditation (1851), which is in many ways the antithesis of Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People. Here the bare-breasted female figure sits in a chair, a cross in her hand and a volume of the history of Italy in her lap. Her intense look is directed backwards to the Milanese uprising against the Austrians in 1848 in which several hundred citizens lost their lives during the five days of insurrection known as the Cinque Giornate (the subject of Carlo Canella’s Porta Tosca in Milano (il 22 Marzo 1848) of 1848–50, later in the show).

The figure, both Everywoman and Italy itself, is occupied with thoughts of what might have been, and although the painting’s title is Meditation it could just as well be Melancholy, the subject of one of Hayez’s works from 1842 using the same model. Hayez, a citizen of Milan and an ardent patriot, felt the ultimate failure of the uprising keenly.

Solar Eclipse at the Fondamenta Nuove (1842), Ippolito Caffi

Hayez, Bagetti, Giovanni Battista de Gubernatis and Giuseppe Molteni are the artists who come out of the exhibition with greatest credit; Ippolito Caffi too, especially his Solar Eclipse at the Fondamenta Nuove (1842), a remarkable image in which the obscured sun leaves a cake slice of the Venetian sky brilliantly illuminated as the rest falls into darkness. Such instances of pictorial daring are rare in a show that offers a fascinating overview, but suggests that in Italy the passionate engagement that was the hallmark of Romanticism was reduced to a bourgeois stock-in-trade of vedute, portraits and medieval scenes.

‘Romanticismo’ is at the Gallerie d’Italia and Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan until 17 March.

From the December 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?