Astonishingly, a comprehensive retrospective of Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) has never been undertaken in North America and the last such exhibition in France took place in 1963. ‘Delacroix’, which opened at the Louvre earlier this year, drew the largest crowds of any exhibition in that museum’s history, some 540,000 visitors. The Metropolitan Museum of Art now presents this giant of European painting to an American public for whom his name is familiar, if not always easily pinpointed – placed somewhere before Impressionism and in blurry juxtaposition to Théodore Géricault (who is also overdue for a such a retrospective). Beyond obvious practical concerns about Delacroix’s prolific production and the difficulty of moving his Salon paintings, it is not easy to translate this artist for today’s general audience. While his daring brushwork ties him to more familiar artists of subsequent generations and his politics provide a compelling story, more often than not, Delacroix’s subjects are obscure and charged with sexualised and orientalised violence.

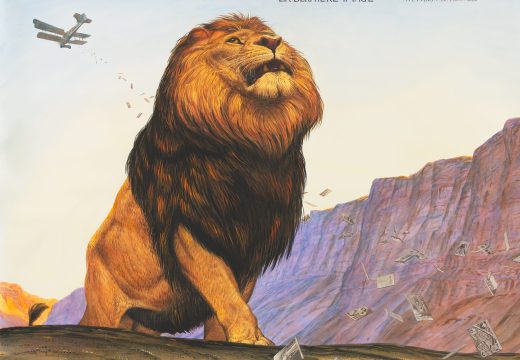

Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi (1826), Eugène Delacroix. Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux. Photo: © Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux, ville de Bordeaux

At the Louvre, with its easy access to a surplus of important paintings, Delacroix was presented in a densely hung, chronological arrangement that carefully chronicled his biography and stylistic development. His early dependence on and then departure from Géricault was made beautifully evident. Freed, perhaps, by a necessarily more limited checklist, the Met’s associate curator Asher Miller has struck an intelligent balance between chronological and thematic arrangements.

At moments this leads to odd omissions (Géricault’s name does not appear until the third gallery, despite his obvious importance to Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi [1826] in the first), but on the whole the exhibition breaks Delacroix’s vast production down into lasting souvenirs in the form of small, digestible lessons for the public and specialists alike. Two of the most effective of these come early in the exhibition. ‘The Image of the Artist’ section combines works by Delacroix in a range of media from the 1820s into the 1840s, which portray the figure of the tortured, Romantic genius in guises ranging from a commanding Self-Portrait (1837) from the Louvre to a cast of literary and historical figures, including Michelangelo in his Studio (1849–50) from the musée Fabre, Montpellier, and the meticulously painted Tasso in the Hospital of Saint Anna, Ferrara (1824), from a private collection, which, despite its modest scale, stands out as an extraordinary painting in New York as it did in Paris. In the section ‘Artistic Formation’ a wall of académies in several different modes and copies after Old Masters provides a similarly self-contained vignette that elicits close attention within this grander survey. Perhaps because of the recent exhibition and catalogue ‘Delacroix and the Rise of Modern Art’ at the National Gallery, London, and Minneapolis Institute of Art in 2015–16, far more is made of the artists Delacroix studied than the more blockbuster names, such as Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso, whom he inspired.

Christ in the Garden of Olives (1824–26), Eugène Delacroix. Church of Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis, COARC, Paris. Photo: © Jean-Marc Mose/COARC/Roger-Viollet

The Louvre has been extremely generous with 17 loans, including Women of Algiers in their Apartment (1834) and Young Tiger Playing with its Mother (1830–31); however, in order to convey the grand scale of Delacroix’s most important paintings, the Metropolitan has depended on loans from churches and French provincial museums (Bordeaux, Lille, Nantes). This is an excellent opportunity to see less familiar works: Christ in the Garden of Olives (1824–26) from the Parisian church of Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis, recently cleaned to magnificent effect, and Medea about to Kill her Children (1838), shown next to its luminous oil sketch, both from Lille, are stunning. For visitors unfamiliar with the Louvre’s collections, however, this slightly skews Delacroix’s story. Gigantic Salon paintings are, of course, difficult to move safely, though diplomatic gestures rather than scholarly reasons have, for example, got Liberty Leading the People (1830) to Tokyo in recent memory, and it has even visited the Met – when it travelled to New York and Detroit as part of the United States Bicentennial celebrations.

Dramatic lighting and walls painted rich jewel tones show this artist’s idiosyncratic, sometimes difficult, palette to its best advantage and several brilliant sight lines – Christ in the Garden of Olives, for example, pulling visitors away from the introductory text panel and into the first gallery – punctuate the exhibition effectively. The restoration of several paintings, notably the Met’s own, wonderfully quirky Basket of Flowers (1848–49) hung next to a related work from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, attest to Charles Baudelaire’s characterisation of Delacroix as ‘a volcanic crater artistically concealed beneath bouquets of flowers’. The vivid, blinding whites (likely inspired by Richard Parkes Bonington), suggest that much of Delacroix’s original visual impact often lies hidden today beneath yellowed varnish.

Sketches of Tigers and Men in Sixteenth-Century Costume (c. 1828–29), Eugène Delacroix. The Art Institute of Chicago.

In both Paris and New York, the curators have been careful to represent Delacroix across several media with works on paper, including the painter’s writings, interspersed throughout the displays. An entire gallery is devoted to his lithographs and another to his fixation on felines (their roars amusingly, if presumably unintentionally, vocalised by the rumble of Jane and Louise Wilson’s Stasi City being screened in an adjacent gallery). Several sheets also allow us into Delacroix’s artistic process as he formulated his vast machines for the Salon, the absence of the latter actually providing us the mental and visual space to look closely at his preparatory materials.

In New York, Delacroix the draughtsman is further explored by the stunning assemblage of more than one hundred works that are a recent gift to the museum in ‘Devotion to Drawing: The Karen B. Cohen Collection of Eugène Delacroix’ (17 July–12 November). The collection includes the bravura ink slashes synonymous with Delacroix’s mature line, but also an important group of drawings related to his training, including a mesmerising series of écorchés. Gathered with remarkable vision, it ensures that the Metropolitan will continue to be a centre for understanding this complex artist.

‘Delacroix’ is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York until 6 January 2019.

From the November 2018 of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home