The American artist is well known for his large-scale watercolours of birds and beasts. His current exhibition at Kasmin Gallery, New York, reimagines the life and times of the Barbary lion, which became extinct in the wild during the 20th century.

What first drew you to the Barbary lion?

I became aware of its existence quite a while ago, and I made some paintings that had this lioness as their subject. They’ve recently declassified the Barbary lion as a distinct sub-species of lion, which is more of biological than cultural interest – my interest in it is cultural. It was a lion that lived not in sub-Saharan but in North Africa, in the Atlas Mountains in what is now Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia. This was the lion that the Romans would have used in the Colosseum, and it later became the sort of go-to lion for zoos and menageries in Europe, because it was just across the Mediterranean.

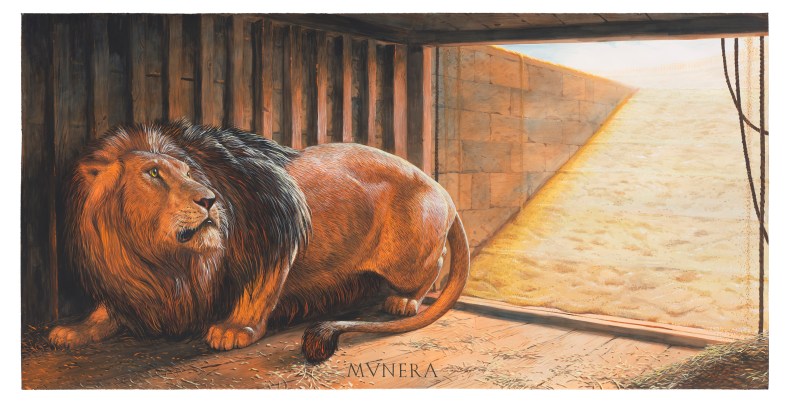

Mvnera (2018), Walton Ford. Courtesy the artist and Kasmin Gallery

Because of the colder climate than sub-Saharan Africa, it had a gigantic mane and a lot of black belly fur. It was a magnificent animal – the type of lion you see the most in art, in Rubens paintings, in Delacroix, in French Romantic sculptures… any time you see a lion in front of a library it’s probably been patterned after one of these North African lions. The MGM lion was more than likely one of them.

I’m interested in how wild animals, rather than domestic animals, become a part of human culture. We’re almost like stalkers of a lion like this, the poor animal. We became obsessed with the fierceness, the ferocity, and the noble look of a lion to such a degree that this animal was driven to extinction in the wild. By the 1960s there were no more lions in North Africa.

In your previous paintings of lions, the animal has often looked tragic, vulnerable – as in The Far Shores of Scholarship [2003] or The Royal Menagerie at the Tower of London – 3 December 1830 [2009]. But in some of the new paintings, the one that reimagines the Great Leipzig Lion Hunt, for example, the lion seems to be lording it over its human surroundings…

I’ve done more pathetic lions. I have a few different moods and modes in the show – and I wanted to move beyond clichés from popular culture, like the idea of the cowardly lion. In 1913 a circus was coming into Leipzig and the lions were being transported in a carriage – it was an old caravan style circus. It was a foggy night and the cage was hit by a streetcar, and eight lions escaped and were wondering around the streets of Leipzig in the fog.

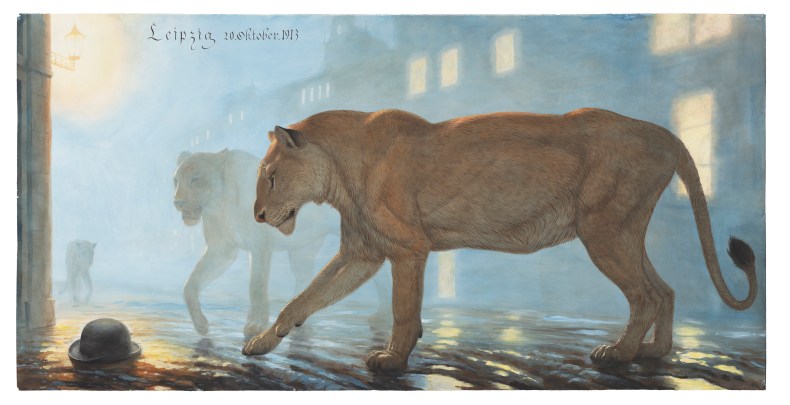

Leipzig 20 Oktober 1913 (2018), Walton Ford. Courtesy the artist and Kasmin Gallery

In the popular press they would have imagined the lions attacking the horses, you know, and attacking people immediately, as if they’re just programmed to destroy everything around then. But these were wild animals and when they got loose they were probably wandering around just trying to figure out what to do, where to go or how to be safe. They’re not usually in a mode of man-eating.

The bowler hat on the ground is surreal – like something left over from Magritte.

I found a contemporary image of the escape, a painting that showed the lions bursting forth from the cage, with men running for their lives and their bowler hats flying off to accentuate the drama. But I wanted a decidedly undramatic moment, to show the curiosity and timid confusion of these lost lionesses, which don’t know where to go or what to do, and don’t know what they’re seeing. I imagined one of the hats that had been left behind: the lions approach it like a strange object, like a turtle or something.

Is the cityscape in that painting a change of direction for you?

Absolutely. For this show I decided to do proper exhibition watercolours. In the past my largest source of inspiration has been more taxonomic natural history imagery, where you have a specimen against a white sheet of paper – you might have a low horizon background but generally you’re trying to show the animal off to best advantage in either a profile or a sort of three-quarters view, as a more-or-less scientific illustration. For this show I was more interested in a painterly mode, and getting into these spaces and these environments.

Another work, Un Homme qui Rêve, imagines Eugène Delacroix devoured by a lion. How far have you been consumed by your subject?

You do go into character, in a way, when you do these. Because they’re narrative pictures, you really live inside them while you’re making them. I find myself making growling noises while I’m painting.

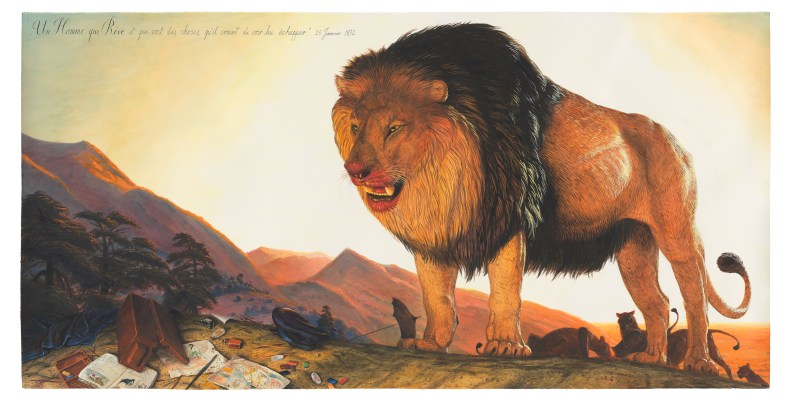

Un Homme qui Rêve (2018), Walton Ford. Courtesy the artist and Kasmin Gallery

I was thinking about how Delacroix went to North Africa when he was a young man, in his 30s, and then for the rest of his life painted Arab subjects in his studio in Paris based on his sketch books from that time. I wanted to imagine Delacroix devoured by his subject matter – and by all the clichés of orientalism, too.

Bill Buford has previously suggested that in your work you project yourself into a world that didn’t yet have a camera. Does that hold true for these paintings?

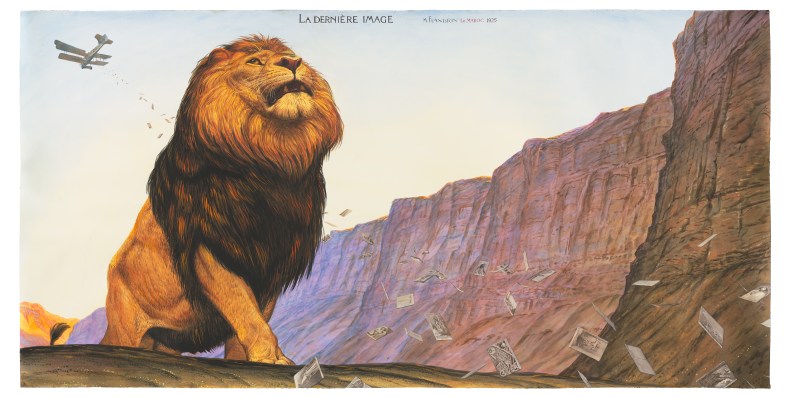

I’m no longer consumed with the idea of pre-photography. The final painting I worked on is about the last photograph of a North African lion in the wild, taken by a guy called Marcelin Flandrin, who was a photographer in Casablanca and became one of the pioneers of aerial photography. He was in a plane going from Casablanca to Dakar, and saw a lion walking in a canyon down below him, and he took a photograph of it, which he sold as one of his postcards. The last painting for the show has the bi-plane passing over this Barbary lion, and all of Flandrin’s exotic, orientalist postcards are fluttering down from the aeroplane, including the photo of the last Barbary lion. It’s an impossible scene but it makes a lot of sense to me.

The thing is, the lion doesn’t give a fuck about whether he’s a star, or whether he’s the MGM lion, or whether he’s this human symbol of nobility, he’s just driven from his homeland, being killed and being imprisoned and driven to extinction… There’s nothing in it for the lion being a superstar of human culture.

La Dernière Image (2018), Walton Ford. Courtesy the artist and Kasmin Gallery

Do you see your art as a type of conservationism?

I don’t like to riff from the headlines. I’m really interested in history: I paint in a sort of 19th-century style so I find myself painting about the 19th and early 20th century a lot. I don’t want to do a painting of a turtle with a fishing net on it – I can’t change anybody’s mind by making paintings that talk about contemporary concerns.

It’s unusual to use watercolour on this scale – and few contemporary painters use it at all. Is it an anachronistic medium?

I was going to use that word. I think there’s an enormous amount of resonance with this medium when it comes to my subject matter: it’s the traditional way to portray an animal from the moment, when you’re in the presence of it. The first real natural history painting is the wild hare that Dürer painted in 1502 – and it’s painted in the exact same way that I’m painting my paintings, except that it’s better.

There’s something visceral and wonderful about an animal that’s painted life size, that’s sort of in the room with you – as in Audubon’s watercolours. Animals never look the way we expect them to – when we go to the zoo we’re like, holy shit, look at the size of that thing, or look at how weird it is, or how it moves. The actual scale of an animal is always a bit of a surprise. I want to capture that: if I paint an elephant or a lion, I want to put it in the room with you and fill your field of vision with it. I want to make paintings that defy the photographic ability to reproduce them. I was recently in Venice and saw the big Tintoretto Crucifixion, in which all the figures are slightly larger than life. The only way to see them is in person: you can’t really have an opinion about Tintoretto unless you’ve been to Venice.

Audubon kept specimens of birds that he pinned into poses before painting them. Do you have a natural history collection?

Not really. There’s a mixture between a 19th-century studio and a very 21st-century approach. I have animal skulls: a few feline skulls, a few canine skulls, and a domestic cat skeleton, which is helpful for all of this, as well as some 19th-century death masks from Paris – there’s one of a big cat and one of a bear. I have plasters from the great animal sculptor, Bayre, who was really good on anatomy, and some pretty detailed little models of big cats by a contemporary Japanese maker. And I have a large collection of plastic animals.

What about taxidermy?

The Museum of Natural History here in New York City has some of the finest taxidermy that was ever executed. The people who worked there were sculptors of the highest calibre, and they would basically make a beautiful sculpture of an animal that was anatomically precise, and then work the skin over that. They’re not stuffed in the style of upholstery, they’re properly mounted in gorgeous poses. I go to the museum and sit and do drawings, or to the zoo and take photographs. And then I sit in front of the computer and do Google image searches like crazy, but only after I have plenty of three-dimensional information. I never take a photographic image and paint it: I always create my own poses from a rough sketch and then try to find material that can help me make that.

For something like fur detail – the way that fur grows on the face of a lion is quite complex – I go to the Museum of Natural History and stand in front of the diorama and draw it, then keep that drawing in my files. Photos never really show fur properly – they blur it out for whatever reason.

Do you have any pets?

As a child I had masses of pets – lots of wild animals that I caught. I grew up in the Hudson Valley, and as a teenager one year I worked on a road crew that was clearing bush for the water department along the road. I used to bring a pillowcase to work to catch something called a pilot black snake – a huge constrictor – and I brought one home and kept in my closet for the summer. I fed it rats, and then let it go in the fall.

My mom never knew what I was going to bring home. I raised a few wild birds: the birds that I brought home flew in and out of my room for an entire season, before I took them back to where I found them and let them go. There were always animals around, but right now I don’t have any – the responsibility is too much.

‘Barbary’ is at Kasmin Gallery, New York, until 22 December.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?