Painting held a particular interest for Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–81), who was born 200 years ago this November. This was perhaps not all that strange in a culture where literature and art were deemed ‘inseparable twins’. Gogol wrote a story that revolved around painting, ‘The Portrait’, in 1835, and his friend Alexander Ivanov depicted them both as prophets with a message for contemporary Russia in his epic canvas The Appearance of Christ to the People (1837–57). In Anna Karenina (1878), Tolstoy introduces the character of Mikhailov, an expatriate Russian artist painting a scene from Christ’s Passion, and the author was painted by sympathetic contemporaries as a moral crusader in a peasant shirt or behind a plough. Dostoevsky shared the common preoccupation with Russia’s destiny and Christian belief, but his engagement with art was of a different order. He forged no close friendships with painters, agreed to sit for his portrait only once and demonstrated only moderate critical acumen when reviewing two St Petersburg exhibitions. More importantly, he maintained a deep reverence throughout his life for Italian, French and German Old Masters, despite developing an increasingly xenophobic ideology after he was allowed to return from exile to St Petersburg in 1859. Particular masterpieces by his favourite painters, Raphael, Holbein and Claude Lorrain, occupy a vital position in the scaffolding he built to support the aesthetic and religious credo developed in his great novels, culminating in The Brothers Karamazov, completed a year before his death.

Raphael’s Sistine Madonna (1512) represented the supreme expression of Dostoevsky’s spiritual and aesthetic ideal. By the time he saw it in the 1860s, the cult of the painting, long established in Russia, was already subject to attack by his ideological adversaries – radical utilitarians who saw greater value in a pair of shoes. When the newly married Dostoevsky fled Russia with his young stenographer wife in 1867, escaping creditors, the Sistine Madonna was the painting above all he wanted to show her. In Dresden, on their belated honeymoon, Dostoevsky would spend hours in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister gazing rapt at the picture. The suffering and tenderness in the Madonna’s face which so moved him can be compared to its expression in Russia’s most famous icon, the Vladimir Mother of God, and in the icon most venerated by the Dostoevsky family, The Joy of All Who Sorrow. If the devout author did not view Russian icons through the same prism as he did Western religious painting, it was because their purpose was to aid prayer; only in the 20th century were they also regarded as ‘works of art’.

Sistine Madonna (1512), Raphael, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden. Photo: Hans-Peter Klut; © SKD

References to Raphael abound in Dostoevsky’s letters and manuscripts. Dostoevsky may have lacked Lermontov’s artistic talent, but as a graduate of the Imperial Engineering Academy he was a trained draughtsman, and he thought in visual images. In the preparatory drawings that filled his notebooks, along with elaborate calligraphy and Gothic arches, he sketched his fictional characters first as faces, including one which resembles the Sistine Madonna. Raphael’s name also appears in Dostoevsky’s novels, most noticeably in Demons (1872), in the liberal intellectual Stepan Verkhovensky’s passionate defence of the eternal values represented by beauty and art. Dostoevsky first conceived this novel during a nine-month stay in Florence. He and his wife lodged opposite the Pitti Palace, a short walk from the Uffizi; he also greatly admired the Duomo, while Ghiberti’s bronze doors for the Baptistery, especially the one depicting Paradise, reportedly sent him into ecstasies.

It was in Florence in 1868 that Dostoevsky completed his novel The Idiot, in which he set out to create an image of a ‘positively good and beautiful man’ in the character of Prince Myshkin. He had recently been shaken almost to the point of an epileptic fit by an encounter in Basel with Holbein’s The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb (1521) and the painting is discussed in The Idiot at two significant junctures. This masterpiece of the Northern Renaissance, in which the revolutionary, hyperrealistic evocation of Christ’s corpse appears to deny his divinity, can be construed as a kind of mirror opposite of the Sistine Madonna. In The Idiot the painting functions as a powerful emblem of Dostoevsky’s central theme – modern society’s loss of faith – yet like so much in his creative universe its meaning in the novel is ultimately ambiguous, as was Holbein’s relationship to the nascent Reformation. Dostoevsky’s characters look up to see a reproduction of Holbein’s painting hung above a doorway, emulating the experience of visitors at the Kunstmuseum in Basel, to whom it appears that Christ’s body is unequivocally succumbing to the all too human process of corruption. In Dresden, Dostoevsky had stood on a chair to examine the Madonna’s face closely. In Basel he risked scandal to study Holbein’s elongated canvas at eye level. Thus he could perceive signs of inner radiance and imminent resurrection which inescapably recall the epigraph from John 12:24 in The Brothers Karamazov: ‘Verily, verily, I say unto you, Except a corn of wheat fall into the ground and die, it abideth alone: but if it die, it bringeth forth much fruit.’ Dostoevsky’s apparently simultaneous combination of traditional Western European perspective with the diametrically opposed ‘reverse perspective’ of Russian icon-painting contributes to the fundamentally modern polyphonic texture of his writing.

An 18th-century icon depicting the Virgin as the Joy of All Who Sorrow. Andrei Rublev Museum of Ancient Russian Art, Moscow.

For his birthday in 1879, Dostoevsky was overjoyed to be given a photographic reproduction of the Sistine Madonna (cropped to exclude saints and cherubs). His wife Anna Grigorievna hung it in a dark oak frame over the couch in his Petersburg study on which he died; during the last year of his life she would encounter him standing before it in a state of profound contemplation, as if it were an Orthodox icon.

A reproduction of the Sistine Madonna also hung in Tolstoy’s study in his last years, the gift of a favourite cousin, although one disciple reported that mere mention of the painting was enough to bring on an ‘attack of suffocating, blasphemous anger’. One wonders how both Tolstoy and Dostoevsky might have reacted to the circumstances in which the Sistine Madonna would one day be exhibited in Russia. At the end of the Second World War the Red Army took the painting to Moscow and, in 1955, at the height of the Thaw, tens of thousands of Soviet citizens queued to see it before it was returned to Dresden.

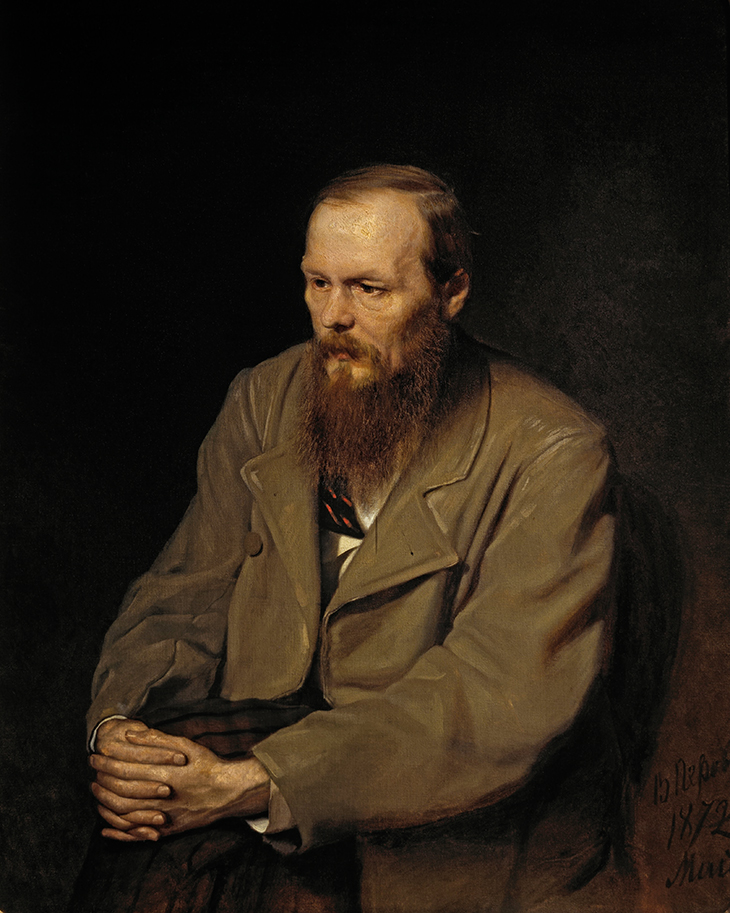

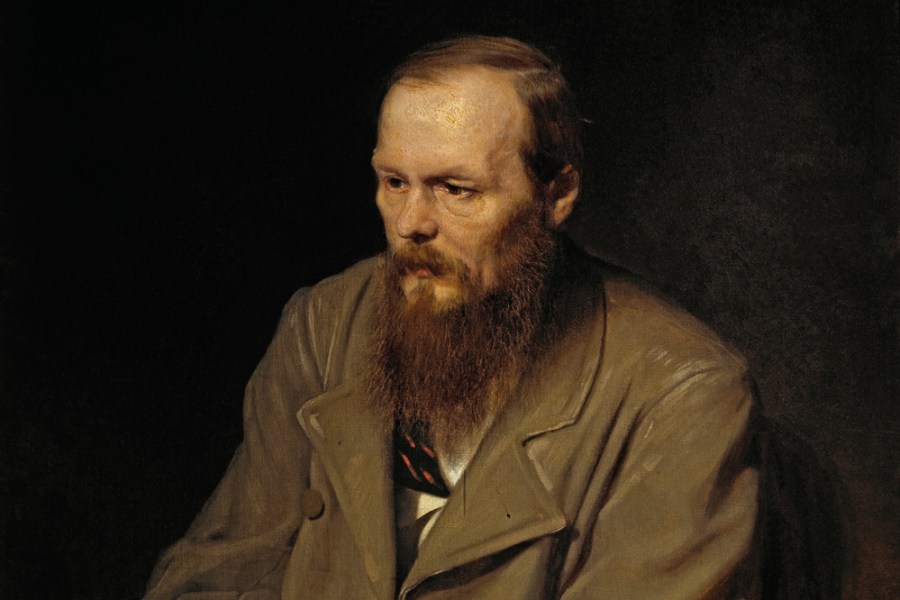

Fyodor Dostoevsky (1872), Vasily Perov. State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

Rosamund Bartlett, a biographer and translator of Chekhov and Tolstoy, wrote the introduction to The Russian Soul: Selections from A Writer’s Diary by Fyodor Dostoevsky (Notting Hill Editions).

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?