The geometric drawings by the Swiss spiritualist and artist Emma Kunz (1892–1963) are like kaleidoscopes: patterns appear to tremble and pulsate as you pass by. From afar, a trio of circular works resemble dartboards – static targets. Come closer and they morph into watchful eyes with stringy, pigmented irises and pupils that constrict and dilate in the light. Kunz predicted that her drawings would be appreciated by future generations and here they are hanging in the Serpentine Gallery, in the first monographic show of the artist in the UK. Dotted throughout the space are stone benches (made from a healing rock Kunz discovered) by the artist Christodoulos Panayiotou, who has been involved in putting the exhibition together – handy if the drawings leave you feeling dizzy.

Kunz grew up in rural Switzerland. She claimed to have discovered her gifts for healing and telepathy at a young age and practised as a naturopath, researching the restorative energies of minerals and plants. She didn’t study art and it wasn’t until her 40s that she began to draw using a technique called radiesthesia. She would consult a divining pendulum, posing a question – from the personal to the political – and finding the answer within the lines that materialised in stops and starts on the page. The sittings could stretch over 24 hours and the drawings, of which there are more than 400 in total and some 65 at the Serpentine, guided her diagnosis of patients.

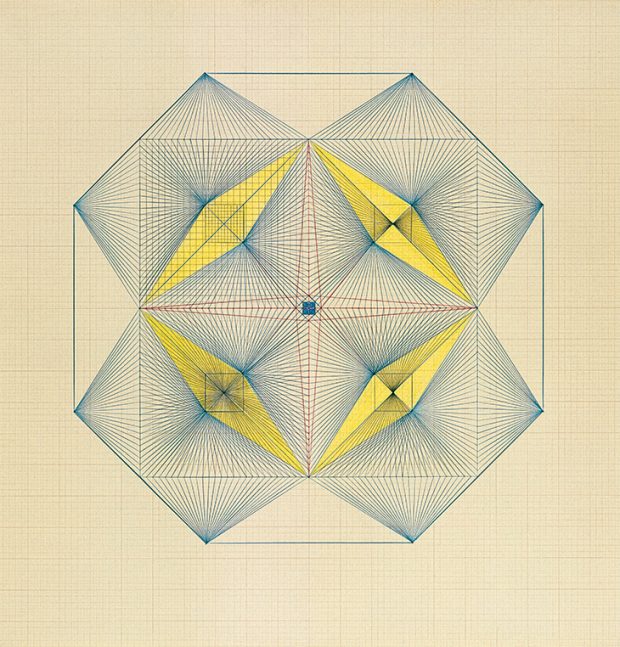

Work No. 117 (n.d.), Emma Kunz. Photo: © Emma Kunz Zentrum

Each exquisitely detailed drawing is comprised of pencil, crayon and oil crayon on a large sheet of graph paper. They may be abstract, but they were created for the purpose of healing – these weren’t simply decorative or deliberatively expressive works of art. Seemingly symmetrical patterns give way to irregularity: initially the four main components of Work No. 117 appear as mirror images but, upon closer inspection, different internal patterns emerge within the elongated yellow diamonds. The ostensibly harmonious arrangement of drawings in the North Gallery is also misaligned.

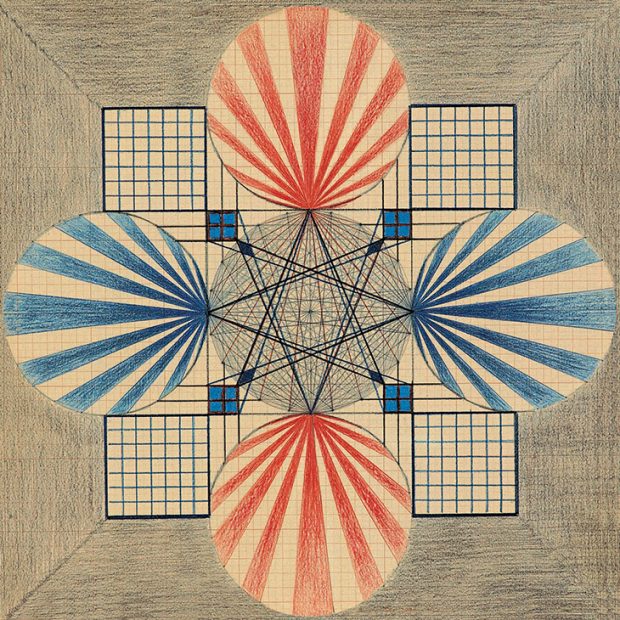

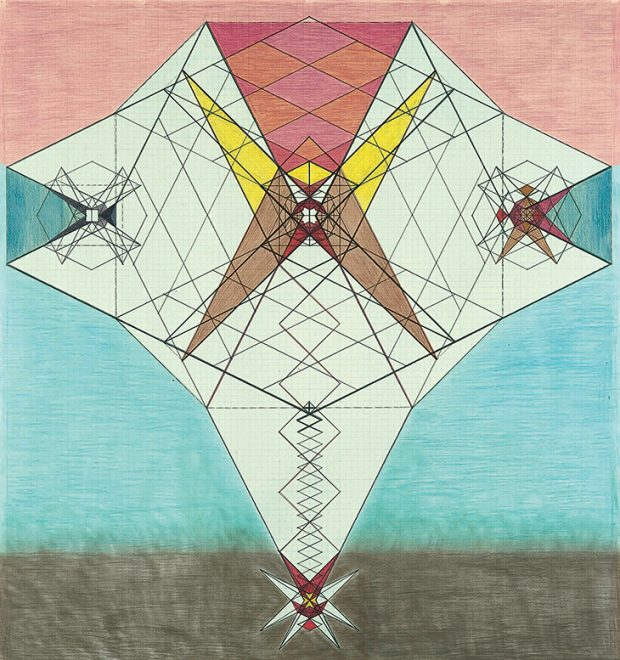

The drawings, so rooted in repetition and ritual, are precise yet tantalisingly imperfect. Colours sharpen and fade within single shapes: the red and blue rays of Work No. 396 grow weaker as they radiate outwards. Kunz’s colouring may not stray outside her razor-sharp lines, but it doesn’t always reach them either, and her marks are visible within rough patches of pastel blues and pinks. There’s a sketchy quality to the drawings, as seen in the lemon-yellow background of Work No. 464, which reflects her ad hoc approach of coming to terms with external forces – namely the laws of nature – on the page. For Kunz, drawing was a way to understand the world, rather than a means of representing it.

Work No. 396 (n.d.), Emma Kunz. Photo: © Emma Kunz Zentrum

Yet, in the 21st century, these works throw up a series of likenesses – aided by the absence of titles and dates. They evoke searing kites, shrewdly spun cobwebs and swarms of butterflies; at times, the colour palette reminded me of the Power Rangers. Work No. 012 offers a hint of perspective, with a murky foreground and what looks like an electricity pylon shooting towards the sky. Work No. 127 features concentric circles unravelling in rows, like bangles on a wrist or a Slinky before it flip-flops down a flight of stairs. Mostly the circles are grey but some curves are picked out, ribbon-like, in pink and yellow. Work No. 100 is a constellation of moons and stars, with the hint of a human figure below, legs spread, elbows bent.

In 1953, Kunz self-published two illustrated books that expressed her desire to share her work, though she never had a chance to do so. Her drawings were first exhibited in Switzerland in 1973, a decade after her death, and since then she has been variously aligned with modernist abstraction and ‘outsider’ artists. She has cropped up in exhibitions alongside the Swedish artist and occultist Hilma af Klint – the subject of a Serpentine exhibition in 2016 – and Agnes Martin. Unlike abstract art, though, Kunz’s drawings fluctuate: form ebbs and flows. Her visionary drawings are the result of a highly charged spiritual practice and, standing before them today, you can almost feel the thread-like lines tingle.

Work No. 012 (n.d.), Emma Kunz. Photo: © Emma Kunz Zentrum

‘Emma Kunz: Visionary Drawings’ is at the Serpentine Gallery, London until 19 May.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home