In this ongoing series, Apollo previews a range of international exhibitions, asking curators to reveal their personal highlights and curatorial impulses. Gemma Blackshaw is the guest curator of ‘Facing the Modern: the Portrait in Vienna 1900’ at the National Gallery in London

Can you tell us a bit about the exhibition?

‘Facing the Modern: The Portrait in Vienna 1900’ explores an extraordinary time and place: the multi-national, multi-ethnic, multi-faith city of Vienna during its reign as imperial capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The period under consideration begins with the Ausgleich (Compromise) of 1867, which was accompanied by the passing of state law to make all citizens of the empire equal for the first time in Austrian history. It ends with the dissolution of Austria-Hungary following its defeat in the First World War in 1918. Within this time-frame, the exhibition looks at the central role played by the portrait in middle-class Viennese society.

What makes this a distinctive show?

‘Facing the Modern’ is a large and ambitious exhibition, but unlike most ‘blockbuster’ shows, it does not concentrate on a single artist. We have the work of some of the most mythologised figures of fin-de-siècle Vienna on display – Klimt and Schiele, Kokoschka and Schönberg – but the exhibition does not focus on them so much as their sitters: the New Viennese. Many of the city’s middle-class families were newly arrived in Vienna. They turned to the portrait to declare their tastes and passions, their ambitions and anxieties, as well as to define their ever-changing relationship with the city. They are the subjects of ‘Facing the Modern’.

How did you come to curate this exhibition?

In 2010 I participated in a workshop organised by the Association of Art Historians on exhibition collaborations between university and museum professionals. The event was memorably entitled ‘Don’t ask for the Mona Lisa!’ and Chris Riopelle from the National Gallery followed it up with a note: what was my latest research, and would it work as a Sainsbury Wing show?

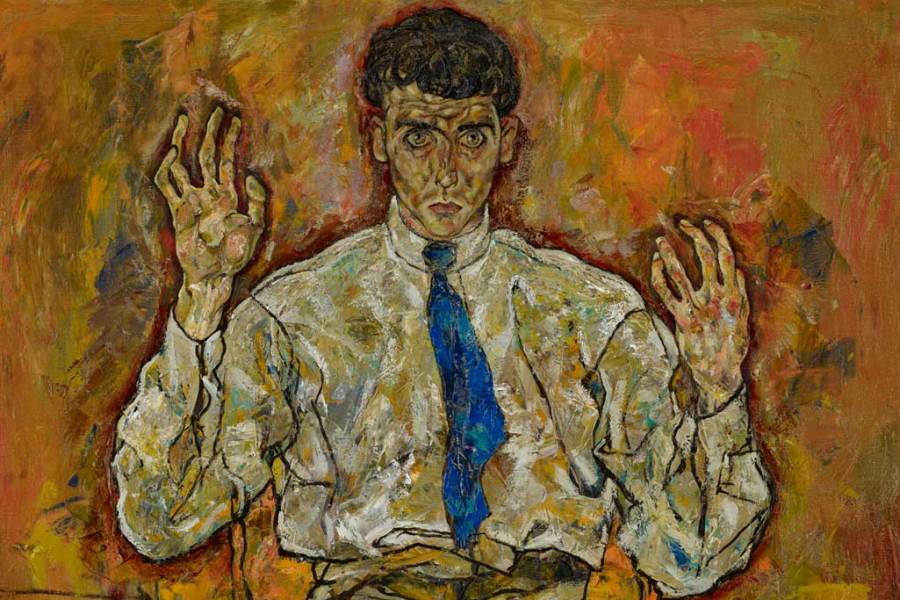

Portrait of Albert Paris von Gütersloh (1918), Egon Schiele © Lent by The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Gift of the P. D. McMillan Land Company

What is likely to be the highlight of the exhibition?

With so many portraits by the city’s most exciting painters on display, it’s impossible to select just one highlight. I think visitors will be particularly thrilled to see both early and late society portraits of women by Klimt. Schiele’s Portrait of Albert Paris von Gütersloh of 1918, on loan from Minneapolis, will be another draw. But I am also sure visitors will be amazed by the work of those artists they encounter for the very first time, such as the exquisite portraits by Isidor Kaufmann. Kaufmann travelled across the Empire painting unidentified Jewish sitters in religious dress in remote places of worship. Highly regarded in Vienna, his portraits ran counter to the city’s trend towards assimilation.

And what’s been the most exciting personal discovery for you?

I really enjoyed meeting Edmund de Waal, acclaimed artist and author of the publishing sensation The Hare with Amber Eyes (2010), at his studio to see the portrait of his great-grandmother, Emmy von Ephrussi, by the Viennese court painter Heinrich von Angeli.

Edmund also showed me a small photograph album containing pictures of Emmy and her friends dressed as their favourite portraits; Emmy appeared as Titian’s Isabella d’Este, Duchess of Mantua, which was in a Viennese collection and was copied by the young Klimt. This album will appear in public for the first time in ‘Facing the Modern’, and Edmund reflects on his family history in the foreword to the book which accompanies the exhibition.

What’s the greatest challenge you’ve faced in preparing this exhibition?

Managing the loan list is always a challenge: a private collector might not want to be parted from a work of art; museums might not be able to lend that portrait but could substitute it with this painting. Holding on to the vision of the original ‘wish-list’ can be difficult. We were very fortunate that much of what we wanted, we were able to obtain.

How are you using the gallery space? What challenges will the hang/installation pose?

The temporary exhibition space on the lower ground floor of the Sainsbury Wing is somewhat inflexible… But the exhibition designer, Alan Farlie of RFK Architects, has divided the largest room to create two corridors of portraits. Anxious sitters, with tense shoulders and clenched hands, stare one another down; for the visitor to the exhibition, it will be an intense viewing experience.

Which other works would you have liked to have included?

We have obtained some of the most spectacular paintings from public and private collections in Vienna: 10 portraits from the Belvedere, for example, and another 10 from the Leopold Museum. But some works of art are both too central to displays and too fragile to travel. Klimt’s Portrait of Sonja Knips of 1898, widely regarded as Vienna’s first truly modern painting, was such a work.

‘Facing the Modern: the Portrait in Vienna 1900’ is at the National Gallery, London from 9 October 2013–12 January 2014.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home