Football is a simple game, as Gary Lineker and Bill Shankly separately observed, but the simplicity of the game itself belies the complexity and intrigue of the things that attend it. The Design Museum’s exhibition, ‘Football: Designing the Beautiful Game’, is a joyful tour through the evolution of the stuff that seems peripheral to the game itself, but is integral to our experience and understanding of it: the shirts, the boots, the stadiums, the fan culture, the posters, the inflatable unicorns.

We start with boots, and gratitude to the Football Association for banning the use of ‘dangerous protrusions’ such as nails as far back as 1863. What’s fascinating about seeing the development of boot design laid out chronologically in this way is how precisely form follows function, whether that be how studs change over time or the positioning of laces to better enable a clean contact with the ball. The designs are increasingly bold, colourful and sleek in themselves, but those choices are nearly always in the service of what the boot is for.

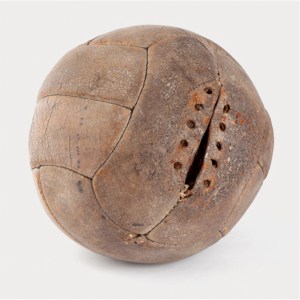

World Cup match ball, supplied by Argentina and used in first half (1930). National Football Museum, on loan from the Neville Evans Collection

As with boots, with balls, from a frankly dangerous-looking animal bladder used at Harrow School in the 19th century, through an Argentinian patent for a ‘Superball’ in 1931, which marked the beginning of balls that did not require a leather lace and could be inflated from a small air valve, thus greatly improving things for everyone. We end up with Nike’s 2020 innovation, Nike Flight, which, the company claims, makes for 30 per cent ‘truer flight’ than its previous Merlin ball – and is sad news for those of us who prefer a more hit-and-hope approach to the game.

But football is about more than just the players’ equipment. The exhibition explores the design legacy of fandom through sections on pin badges, memorabilia and, most arrestingly, programmes and fanzines. Some of the historical graphic design on show here is striking and perhaps at odds with the stuffier perceptions of the clubs themselves at the time. Coventry City’s ‘Sky Blue’ match day programmes, mostly from the 1970s, are prominently displayed: they’re vibrant, modern and playful.

An interesting section on football stadiums takes in Archibald Leitch’s early 20th-century blueprints for Arsenal’s former ground, Highbury, and much more besides, ending again in north London with Populous’s extraordinary Tottenham Stadium, laser-focused on the quality of the match-day experience from access to acoustics.

Render of the new Forest Green Rovers stadium designed by Zaha Hadid Architects. Courtesy Design Museum, London

More interesting than these though, are those stadiums which engage directly with their surroundings: Forest Green Rovers’ Eco Park Stadium, for example, designed by Zaha Hadid Architects, will be an all-timber, carbon neutral stadium in the Gloucestershire countryside, powered by sustainable energy and surrounded by meadows. The sustainable ethos extends throughout the club, with kits made from bamboo, recycled plastic and recycled coffee grounds, while the pitch is watered with recycled rainwater. It may be wishful thinking to link a green philosophy to success on the pitch (cynics would say that money has far more to do with it), but it’s noteworthy that Forest Green Rovers’ eco-drive has coincided with the team’s most successful era in history, culminating in promotion this year from League Two to League One.

Similarly engaged with its locale is the Estádio Municipal de Braga, in Portugal, designed by Eduardo Souto de Moura at the turn of the millennium. Built into the side of a quarry, with a rock face on one side and the city on the other, it’s a democratic masterpiece, providing generous sightlines to the pitch even from outside the ground.

Installation view of the Subbuteo Superhero series by Julian Germain (with Nick Kidney) (1997). Photo: Felix Speller

‘Football: Designing the Beautiful Game’ is an exhibition that tells you plenty of things you didn’t know, but perhaps its greatest strength is its wholehearted celebration of the nostalgia which suffuses football fandom. A display of classic football shirts makes a subtle point about the importance of design for protecting marketable properties from counterfeiters, but mainly it celebrates the garishness of shirt design while gently reminding the viewer that the late ’80s and early ’90s were the best for that, as for much else.

A display of posters for various World Cups through the years is equally joyful, with Joan Miró’s design for Espana ’82 the absolute highlight among many. The exhibition ends with a look at football games, Subbuteo and FIFA and Football Manager among others, and the whole thing feels like a warm bath of pleasure.

In Apple TV’s recent hit show, Ted Lasso, one of the characters, Dani Rojas, has a mantra, often repeated: ‘Football is life.’ The scope and execution of this exhibition proves the truth of that mantra in spades.

‘Football: Designing the Beautiful Game’ is at the Design Museum, London, until 29 August.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?