From the April 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

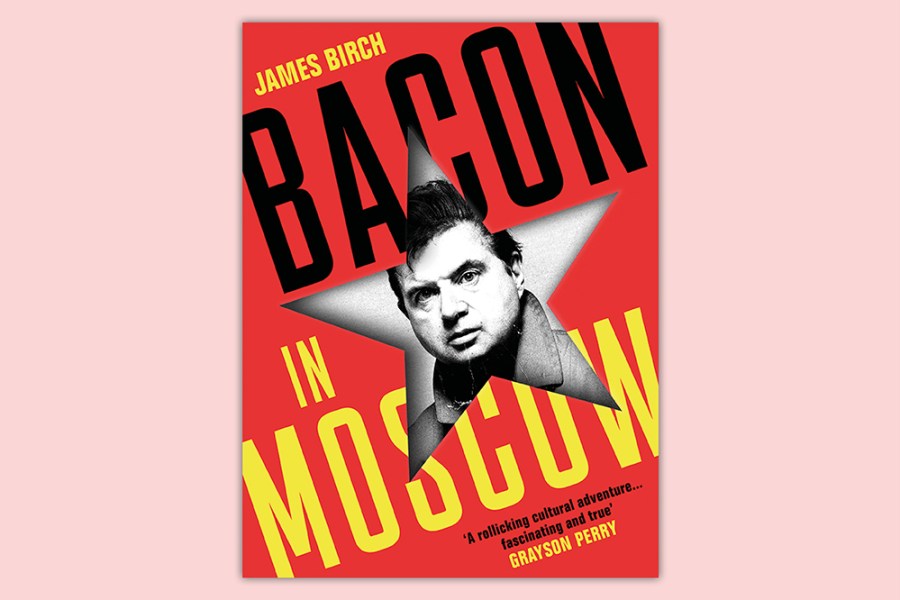

As his plane touched down in Moscow in 1986 the young English gallerist James Birch saw ‘low grey clouds, military vehicles and […] apparently endless birch forest’. It was, he says, ‘exactly what I expected to see’. Birch was there on a wing and prayer, trying to get some of his stable of young contemporary artists, which included a nudist collective and a young Grayson Perry, a gallery show in the Soviet Union. This, he soon realises, was never going to work, but when his KGB minder-cum-cultural-collaborator, Sergei Klokov – who serves as the book’s amoral anti-hero – introduces him to some penniless Soviet artists, they soon all have the name of the same Western artist on their lips: Francis Bacon. As it happens, Birch has known Bacon since childhood, and an idea takes root.

Birch’s account of his struggle to stage the show, the first of a living Western artist ever to exhibit in the Soviet Union, barring Chagall, who was after all born in the Russian empire, reads as if he were recounting it to you over drinks at the Colony Room – which, it seems, is where almost everything got done in the London art world of the 1980s. As well as an intriguing portrait of Bacon himself, there are cameos from Soho sleaze baron Paul Raymond, Grayson Perry and Grisha Bruskin, as well as (inevitably) a raven-haired Russian beauty, the fashion designer and KGB informant Elena Khudiakova, and the great textile expert and scholar of Dagestan Robert Chenciner, whose idea it was for Birch to go to the Soviet Union in the first place.

But beyond being a garrulous yarn of a memoir (the word ‘rollicking’ is used twice on the dust jacket), the book is a record of an extraordinary encounter at a momentous time. Based on Birch’s journals, letters from Bacon, Klokov and others, and illustrated with the author’s pictures of Russia and a gazetteer to the Bacon exhibition, with reproductions of all the paintings, there is some proper art history being smuggled into this book, like a bottle of scotch entering the USSR.

Birch gives an engaging account of his struggles to stage the show. First, dealing with an opaque Soviet system in which nothing makes sense: machinations involving the Union of Artists, the delegation to UNESCO and mysterious, unseen wielders of influence. All this would seem like so much Cold-War cliché until he gets back to London to deal with the capitalist equivalent: insurance companies, cultural grandees and gatekeepers from Bacon’s gallery and the British Council – as well as the vanities and resentments of the great man’s inner circle, which ultimately meant that Bacon never travelled to the Soviet Union to see his own triumph.

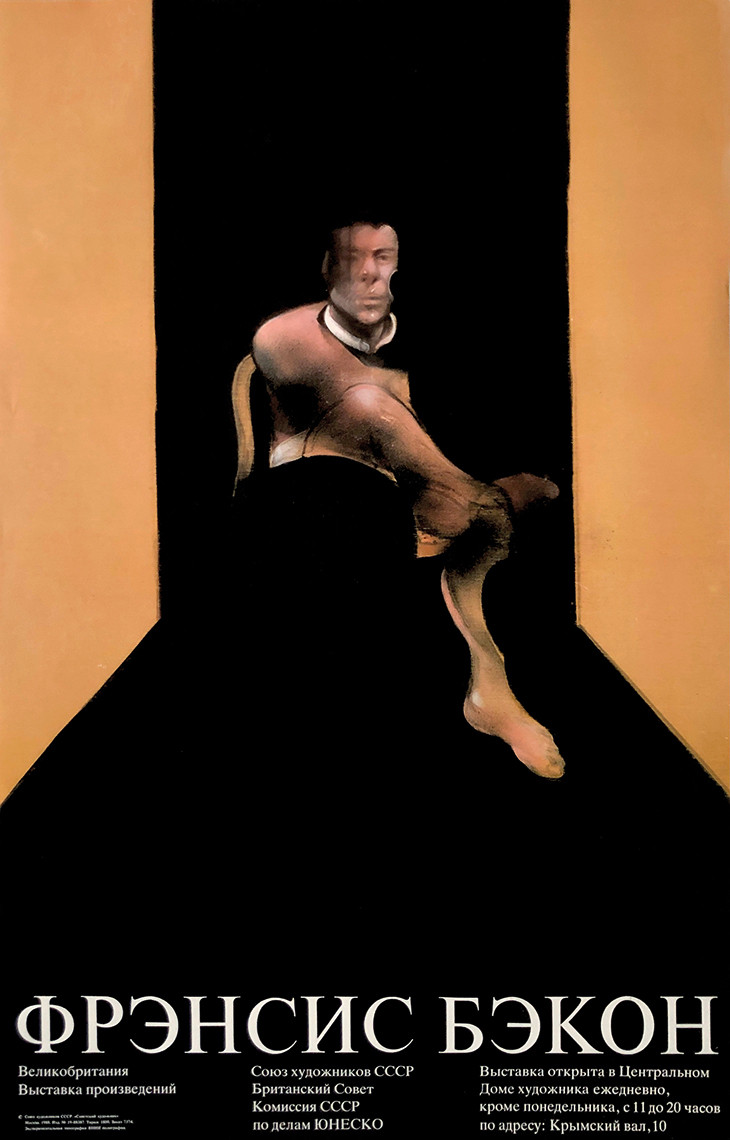

Poster for ‘Francis Bacon’ at the Central House of the Union of Artists, Moscow, 1988. Courtesy Eames Fine Art

The exhibition itself – at the Central House of the Union of Artists in Moscow in 1988 – was a watershed, a set-piece of perestroika, and an indication of what Gorbachev wanted the Soviet Union to become. It would now be called cultural diplomacy, an expression of ‘soft power’ but, as the memoir shows, Russia in the 1980s exerted its own soft power on those from the West, not least James Birch, who later comes to realise he has developed the ‘Russia bug’.

Some 400,000 people visited the exhibition during its six-week run, many queuing for hours for a chance to see Bacon’s disturbing vision of humanity – his twisted forms the polar opposite of the smiling-but-sexless musclebound workers and peasants of so much officially sanctioned art. Indeed, only one painting was forbidden by the Soviet censors, Triptych from 1972, which depicts gay sex. Birch had been warned by Klokov not to include too many ‘cock-exalting’ pictures, and Klokov later provided the excuse to the Independent that its inclusion might have led Soviet society to dismiss the entire show. Even so, the reception was not universally positive. Included as an appendix are selections from the visitors’ book: ‘I haven’t seen anything like this before in my life,’ ‘The exhibition reminds me that madness is real,’ and, most memorably of all, ‘We want bacon, not Francis Bacon.’

We all know what happened next. Within four years, the USSR would be no more, although Birch would get one more exhibition in just below the line; he brought Gilbert & George to Moscow in 1990, but does not record what the Soviets thought of their underpants. The borders would open – for those who could afford travel – and the entirety of Western modern art would become available to the peoples of the Soviet Union. It was a two-way street of course. Russian artists such as Bruskin would become millionaires and move to New York, while some of Klokov’s circle (though not Klokov himself) would become billionaires and furnish their London homes with paintings by Bacon. James Birch would become rich and successful, though as this book shows he would never lose his roguish, self-deprecating charm, and has never left the demi-monde of the Soho art scene.

There is a particular pathos reading Bacon in Moscow now, as Russian aggression flattens cities in Ukraine and the resulting sanctions cut off Russia from the West more than at any time since Birch’s first visit in 1986. The Russian invasion of neighbouring Ukraine shows that the experiment that began during perestroika has definitively failed. The country is again becoming the secretive pariah state in which Birch landed all those years ago, with KGB-style surveillance, low grey clouds and military vehicles on the runway.

From the April 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home