From the February 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

I had, until recently, never seen one of George Bissill’s devastating pictures. This is a shameful admission because before becoming an artist Bissill had been a coal miner, and the mines were his inspiration. The mines had also inspired D.H. Lawrence – England’s first working-class novelist and the subject of my latest biography – but it was only after Burning Man was published last summer that I read Kate Pattinson’s George Bissill: Life and Art and realised that the two men, who were contemporaries and near neighbours, were also blood brothers.

There was an auction of Bissill’s work in December but my bids were unsuccessful, which means that currently all I have of him are the images in Kate Pattinson’s book. The underworld scenes are tense with drama.

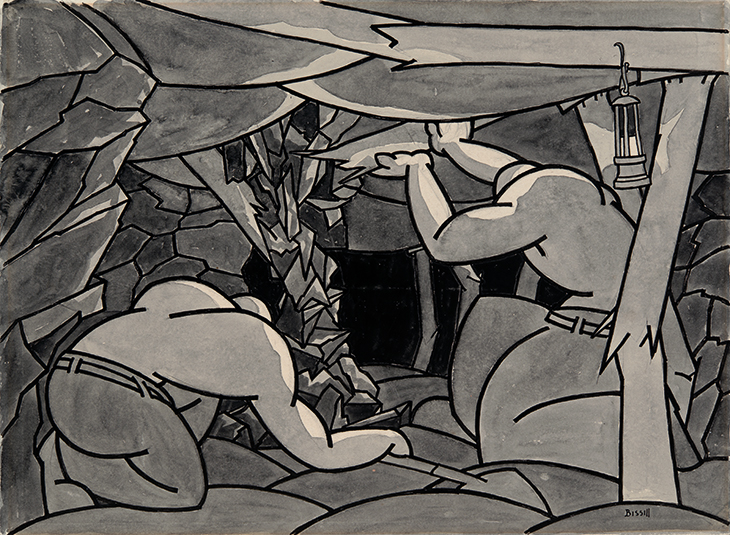

Britain’s Coal (n.d.), George Bissill

The one I am looking at now, a lithograph from 1925 called Britain’s Coal (used on a poster promoting the London and North Eastern Railway), contains the vast naked torsos of two miners in a subterranean corridor. The exaggerated back and arm muscles seem modernist in form but also cartoonish: the men look, in fact, like Popeye the Sailor. The roof, which supports a mile-high mountain of earth and rock, appears to rest on the shoulders of the first of these Atlas figures. The second, on his knees, is hammering at the coalface with blocks of iron. Between them a lamp casts long shadows. The image could illustrate George Orwell’s description of a mine in The Road to Wigan Pier (1937): ‘Most of the things one imagines in hell are in there: heat, noise, confusion, darkness, foul air, and, above all, unbearably cramped space. Everything except the fire, for there is no fire down there except the feeble beams of Davy lamps and electric torches which scarcely penetrate the clouds of coal dust’. The most infernal aspect of Britain’s Coal is that while the shale walls appear to be closing in, there is no exit in view.

The miners Orwell met were ‘small’ men – ‘big men are at a disadvantage in that job’ – but Bissill’s miners are not men at all. They are Atlantes. In A Fall of Bind, one of these giants supports a broken beam in an attempt to prevent the roof from caving in. Before he was invalided out of the army in 1918, Bissill was trapped in the bowels of No Man’s Land when the roof collapsed on a tunnel he was digging. For three hours he was buried alive.

A Fall of Bind (n.d.), George Bissill

George William Bissill was born in 1896 and raised in the mining village of Langley Mill, on the borders of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. Two miles away on the other side of the Erewash canal lies Eastwood, where Bissill’s father had been born and where the Lawrence family lived. Lawrence, whose father was also a miner, described the landscape as a combination of rural beauty and industrial squalor: yew trees, rabbit holes, pit heads, slagheaps, and black wheels spinning fast against the sky. Bissill’s watercolour Gallow’s Inn Colliery depicts the same strange territory.

Gallow’s Inn Colliery (1920s), George Bissill

As a toddler, he drew on the walls and doors of his home; at school, young George copied two Landseer paintings which were then framed and displayed. Bissill began working with the pit ponies who transported the coal through the tunnels at the age of 13. When he returned to the pit after the war, Bissill experienced acute claustrophobia and so he briefly enrolled at Nottingham School of Art. The tutors had nothing to teach him. ‘The mine is in short the only art school I ever had,’ Bissill explained. ‘In the mines I learned the significance of the great effort that is daily expended in the dark, the crouching attitudes, the strain of muscles, and the constant anxiety.’ Moving to London, he became a pavement artist and was discovered by the Evening News, who commissioned him to draw caricatures for their pages.

It was his miners that got him noticed, and Bissill’s first exhibition was at the Redfern Gallery in 1925. The newcomer had, critics said, an ‘inner consciousness’ of ‘what was truly real’. I can imagine, from the experience of Lawrence, how much snobbery and condescension Bissill will have had to stomach. The people who praised his ‘authenticity’ will have never in their lives treated as an equal someone who had not come out of the same drawer as themselves. The ‘pitman painter’ went to Paris and was momentarily fashionable; he experimented with woodcuts, he created posters, he even designed furniture for the art and ballet critic Arnold Haskell. In the 1930s he painted rural scenes in watercolour, at which point he dropped out of favour. When he died in 1973, Bissill had been long forgotten.

His range was remarkable, but it is the underworlds I most admire. Bissill’s miners are in hell, but they are also the roots of civilisation because civilisation is founded on coal. ‘Practically everything we do,’ realised Orwell, ‘from eating an ice to crossing the Atlantic, and from baking a loaf to writing a novel, involves the use of coal, directly or indirectly.’ I never knew, when I was driving through the Midlands with my family as a child, that hundreds of feet below me miners were crawling to work and squatting in the dark before coal seams. ‘Yet in a sense it is the miners who are driving your car forward,’ Orwell wrote. ‘Their lamp-lit world down there is as necessary to the daylight world above as the root is to the flower.’ George Bissill, like D.H. Lawrence, showed us the invisible.

From the February 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home