When it was revealed to the public in 1889, the Eiffel Tower had many detractors who saw it as a useless and monstrous enemy of French taste: Guy de Maupassant called it a ‘nightmare’; Joris-Karl Huysmans, a ‘suppository’. Nowadays the beauty of Gustave Eiffel’s lattice metalwork feat of engineering has long been acknowledged, and the Parisian landmark has become so familiar that few people today question its merits or indeed think of the French capital without seeing the Eiffel Tower at its centre. But how did the tower come to rise? Martin Bourboulon’s new film, starring Romain Duris as Eiffel, tells the story of the monument’s origins and of the man behind the monument.

It is perhaps surprising that this story hasn’t been tackled on film before and, indeed, as a project Eiffel has been 25 years in the making, undergoing several false starts. It might, for example, have been made instead in 2000, by Luc Besson and with Gérard Depardieu and Isabelle Adjani in the starring roles. Bourboulon, whose next film is to be a lavish two-part adaptation of The Three Musketeers, shares with Besson a desire to compete with Hollywood super-productions. The film’s producers are confident that it could be a French answer to Titanic.

Though it is more modest in scale and budget than Titanic, there is certainly something epic about the story of the visionary engineer-artist. When we first see Eiffel, he stands at the top of his tower, windswept like the captain of a ship and surveying the city below. Flashbacks take the story back to 1887, when the French government wanted Eiffel, a celebrated bridge engineer and the man who had built the armature of the Statue of Liberty, to create ‘another symbol’ to be a salient feature of the International Exposition of 1889, held as a celebration of the centenary of the French Revolution.

Emma Mackey and Romain Duris in ‘Eiffel’.

But this is no strait-laced historical biopic, rather it is a fiction freely inspired by historical events. Throughout this highly kinetic film, the charismatic character of Eiffel, in his open-necked shirts, moves and speaks with a freedom that is more in tune with the 21st century than with the fin de siècle, while his (fictitious) love interest, Adrienne Bourgès (the excellent Emma Mackey, underused here) is a proto-feminist free spirit who likes to wear trousers in spite of her bourgeois father’s disapproval. No matter. This is pure entertainment, and an early scene where Eiffel, suddenly seized by his vision, declares tersely: ‘A tower. Three hundred metres. Entirely of metal.’ sets the tone for the maverick endeavour where he battles against sceptical investors, hostile journalists, workers threatening to strike and, most challengingly, the dangers of mud and subsidence on the banks of the Seine.

The role of Adrienne as catalyst and muse for the conception and building of the tower is the weaker aspect of Eiffel. Though Duris and Mackey have plenty of on-screen chemistry, the character of Adrienne is underwritten. A melodramatic scene where, spurned by Eiffel, the young woman rashly throws herself into a river feels like a much diminished echo of similar scenes in Vertigo and Jules and Jim.

But perhaps the main reason why Eiffel and Adrienne’s romance remains a secondary strand is that Eiffel works best as a thriller about engineering, complete with death-defying acrobatics. What is most enjoyable about the film is a sort of inverse effect of the chilling ending of Planet of the Apes, in which the Statue of Liberty is suddenly revealed half buried in the sand, suggesting that the planet experienced a nuclear catastrophe. Here instead we experience the thrilling, uncanny appearance of the tower’s colossal support piers in what was an empty field. There is a highly suspenseful scene in which segments of the tower are matched up into precise alignment by Eiffel and his workmen in mid-air by painstakingly calibrating pressure and depth with sand and water.

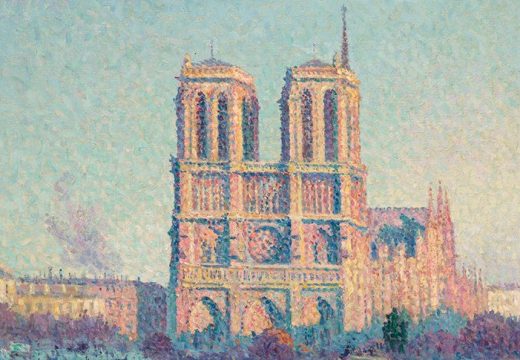

And then there is the beauty of the Parisian period setting, often foggy and dreamlike, punctuated by black top hats and grey umbrellas, recreated in the muted colour palette of a Caillebotte painting.

‘Eiffel’ is released in cinemas in the UK on 12 August.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home