The modern artist, Hans Hess declared in a lecture in 1964, ‘thinks of himself as an independent genius, but he is only a tool in that greater social machinery which owns and controls him’. This observation was typical for an art historian determined – as the art historian Quentin Bell put it – to confront not so much ‘the facts of life’ as ‘the more dangerous facts of class’.

Fifty years on from Hess’s death, his name is rarely mentioned along that of fellow Marxist art historians John Berger, Arnold Hauser and Frederick Antal, nor among more mainstream friends and contemporaries such as Bell, Kenneth Clark and Michael Levey. But Hess, who worked as a curator in Leicester and York, left behind a body of work – much of which has just been published together for the first time – that grappled with both the purpose of art and its articulation throughout modern history. His two significant monographs, on George Grosz and Lyonel Feininger, reflect an intimate knowledge of their subjects that goes beyond scholarly enquiry, since Hess’s induction into art history was not in the university, but through family fortune and a series of twists of fate.

Fifty years on from Hess’s death, his name is rarely mentioned along that of fellow Marxist art historians John Berger, Arnold Hauser and Frederick Antal, nor among more mainstream friends and contemporaries such as Bell, Kenneth Clark and Michael Levey. But Hess, who worked as a curator in Leicester and York, left behind a body of work – much of which has just been published together for the first time – that grappled with both the purpose of art and its articulation throughout modern history. His two significant monographs, on George Grosz and Lyonel Feininger, reflect an intimate knowledge of their subjects that goes beyond scholarly enquiry, since Hess’s induction into art history was not in the university, but through family fortune and a series of twists of fate.

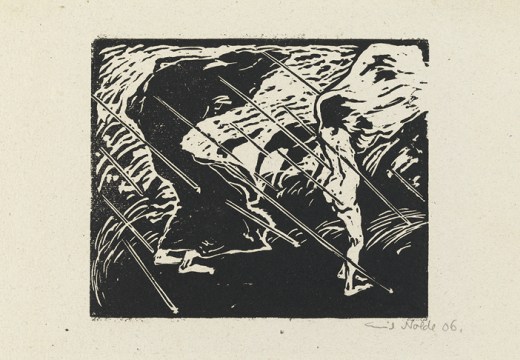

Born in the central German city of Erfurt to a family of industrialists in 1907, Hans ‘assumed, as the elder son, that he would eventually own a shoe factory’, his daughter Anita Halpin says. Hans’s parents Alfred and Tekla were noted collectors, having sponsored exhibitions and paid for materials for ‘artists in difficult times’ – mainly Expressionists and the first Bauhaus generation. The family guestbook, later published by Hans as Dank in Farben (‘thanks in colour’), collects messages, sketches and watercolours from artists who visited the house – including Max Pechstein, Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee.

Woodcut of Alfred Hess by Max Pechstein, from Dank in Farben (1957). Bauhaus Archives, Berlin

The Wall Street Crash and the rise of the Nazis threw Hans’s business career off course. After waiting in vain for a May Day uprising to topple Hitler in 1933, he fled to Paris before moving to London in 1935. Here he played a key role in founding the Free German League of Culture, in which he would work closely with the artist John Heartfield. Hess’s active anti-Nazi credentials and Jewish heritage were not sufficient protection from wartime internment, which he spent on the Isle of Man and in Canada. He was allowed to return to Britain in 1942, and was posted to Leicestershire as an agricultural worker.

Cover of the catalogue for the exhibition of German Expressionism at York City Art Gallery in 1953, curated by Hans Hess

This move, more than any other, would come to define his future. After Tekla joined him in Leicestershire, the Hess name was recognised by the Leicester Museum and Art Gallery’s curator Trevor Thomas, who had a long-standing interest in German Expressionism. Arranging for Hans to be released from war work, Thomas engaged him as an art assistant at the museum shortly before staging a major show. ‘Mid-European Art’, staged more than a year before the end of the war, that put Leicester on the map as host to the first exhibition of German art since the New Burlington Galleries in 1938. The Leicester show included 50 works from the Hess family collection – many more had been seized by the Nazis or sold below value as the family fled Germany – and the city maintains an extensive Expressionist collection to this day.

It put Hess on the map, too. In 1947 he moved to York, where he would work for the next two decades. He was ‘an outstanding gallery administrator but he was not an art historian’, his assistant and successor at York John Ingamells, later director of the Wallace Collection, rather sniffily observed.

‘Both are true in contemporary terms,’ Halpin says. ‘He was a damn good administrator. In an annual review of public galleries, York was rated best outside of London in having the widest breadth of collection, covering most English and European schools. [He had] a very imaginative approach to acquisitions. But he was not what was expected of the curator of an art gallery.’

Hess had no formal training until late in his career, latterly completing an MA under Bell’s supervision and becoming York University’s first visiting lecturer. Later, alongside Bell, he became a founding father of the art history department at the University of Sussex. While perhaps too foreign and too Marxist to be given a knighthood, he was Establishment enough to merit an OBE. ‘He was probably difficult to assess for some people because he was quite obviously not English, but his English was perfection,’ Halpin says.

Hess had no formal training until late in his career, latterly completing an MA under Bell’s supervision and becoming York University’s first visiting lecturer. Later, alongside Bell, he became a founding father of the art history department at the University of Sussex. While perhaps too foreign and too Marxist to be given a knighthood, he was Establishment enough to merit an OBE. ‘He was probably difficult to assess for some people because he was quite obviously not English, but his English was perfection,’ Halpin says.

The first two volumes of Hess’s selected writings, published by Manifesto Press, consist mainly of lectures given at York and Sussex and reflect his distinctively acerbic voice. In Jacques-Louis David, for instance, he finds ‘the almost unique figure of a conscious artist and practical administrator whose every action and work of art is inspired by a political conviction’, yet in his later Napoleonic commissions ‘the beginnings of that long line of dreary paintings about which nobody cares any more’.

As technological advances call the myth of artistic genius into question once more, Hess’s argument that ‘the illusion of art is the surcharge the modern collector has to pay for’ feels more relevant than ever. Yet nor should we forget his passionate defence of fine art and its ‘tendencies towards clarification’. Just like he concluded at that lecture in 1964, ‘As long as we shall have to live in a world with shadows, we shall have need of some light.’

Portrait of Hans Hess in Switzerland in the late 1960s, taken by an unknown photographer. Private collection

Hans Hess: Selected Writings is published in two volumes by Manifesto Press.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

‘Like landscape, his objects seem to breathe’: Gordon Baldwin (1932–2025)