This summer ‘Henry Moore: Sharing Form’ has transformed Hauser & Wirth Somerset into something of a sculpture park, with work from the entirety of Moore’s career filling all five galleries and every outside space. The title of the show indicates the wide range of influences Moore drew on while making his sculptures – beyond the reclining figures that made him so internationally famous. Throughout the exhibition, reference is made to visual cultures from across the globe, from Carnac to Cornwall.

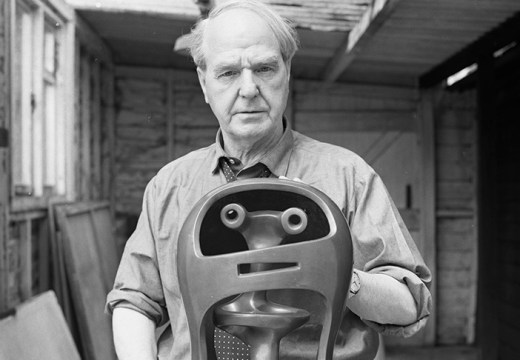

Incorporating Celtic cruciforms and ‘North-West American totem poles’, four examples of Moore’s Upright Motives open the exhibition, a fusion not only of cultural influences but geometric and organic shapes with bodily allusions, in vertical, somewhat disjunctive stacks. They were conceived in 1955 as an architectural commission for the new Olivetti building in Milan, a low one-storey building which prompted Moore to create the upright verticals as a visual counterpoint. The scheme was abandoned, leaving the Upright Motives as residual sculptures which feel experimental. Judicious positioning in the Threshing Barn, the sensitively restored 18th-century architecture of Hauser & Wirth Somerset, encourages the viewer to move around the space, making a convincing argument for the case that sculpture does not have a ‘front’ and should be experienced in the round. While the forms may feel occasionally clunky, as the viewer encircles them the varying textures of surface and patinas become prominent, highlighted by the contrast with scratched and marked original flag stones, wooden beams and carefully conserved stone walls.

Installation view of ‘Henry Moore: Sharing Form’ at Hauser & Wirth Somerset. Photo: Ken Adlard; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

The second room begins the show’s premise proper, taking us back to Moore’s visit to Stonehenge as a student in 1921. Arriving late, Moore couldn’t wait until the next day and visited the site by moonlight which, as he recalled in 1974, ‘enlarges everything, and the mysterious depths and distances made it seem enormous’. Moore’s Stonehenge suite of lithographs, made more than 50 years after his initial visit, give a sense of these impressions, some depicting monumental forms glowing massively above tiny indicative figures. Many of the images were derived from photographs taken by an assistant when Moore decided to revisit the subject, which allowed him to zoom in and crop views that focus on surface, form and texture.

Aside from one later work, all the accompanying sculptures are from the 1930s. Carved in a variety of tactile stones, from African wonderstone to Green serpentine, these were created at a time when Moore was a regular visitor to the British Museum. Like many of his peers, he sought a precedent for the ‘direct carving’, of which he was a leading proponent, in various non-Western cultures from pre-Columbian to West African. The visit to Stonehenge and research trips to the British Museum indicate something about Moore as a young man, attempting to connect with how different cultures engaged with sculptural form. The dialogue between the carvings and lithographs makes each greater than the sum of their parts, highlighting the texture of the stone in both. There are abstract or architectural forms to be found within carvings where first one sees heads and bodies, and figures and faces emerge from the cropped images of Stonehenge.

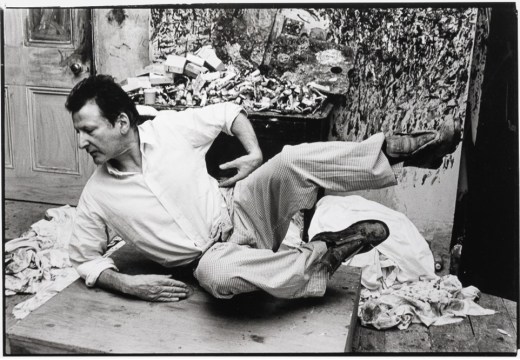

At the heart of the show is the ‘Pigsty’, a cabinet of curiosities curated by the artist’s daughter Mary Moore that includes tools – both designed and improvised – as well as maquettes, flints, organic matter, bones and plaster models from Moore’s studio, intermingled with objects from his personal collection. A Dogon wood carving of a small beast sits near a ceramic modern Peruvian twin figure, an Inuit carved whalebone, Sepik river bone daggers from Papua New Guinea, a pre-classical fragment and a Roman stone figure. None are dated, the collection seemingly amassed for Moore’s interest in the shapes, materials or texture rather than a specific interest in or knowledge of the individual cultures, their objects and context.

The selection is described as ‘a portal into the alchemy of the sculptor’s mind and process’, giving us an insight into ‘Moore’s vocabulary of shapes and forms.’ It offers a sense of what surrounded Moore in his daily endeavours, though the collection is so wide-ranging to be almost no use as an indication of specific cultural influences. Rather we see Moore’s own artistic sensibility through the objects he collected, just as, when he saw the civilians sheltering in the underground from the Blitz, he famously recalled that ‘I had never seen so many reclining figures’.

Installation view of ‘Henry Moore: Sharing Form’ at Hauser & Wirth Somerset. Photo: Ken Adlard; courtesy Hauser & Wirth

The penultimate room gathers three monumental works in bronze, plaster and stunning travertine marble, the latter a duo of figures carved in a manner that resembles the stacked upright motives but smoothed out, undulating and organic. Three smaller bronze forms, clearly derived from collaged plaster, flints and bones, are patinated in different ways: a deep green, a burnished orange, an almost black brown. There is clarity to these works, set against the white walls of the modern gallery which nonetheless gestures to the original rustic architecture in its volumes, echoing Moore’s distillation of form from the busy compendium of objects. It is when the forms are scaled up that Moore is at his best, creating an irresistible interaction with one’s own body.

This peaks with the work that provides the opener and closer to the show, The Arch (1963–69), placed in the central courtyard of the gallery complex. The monumental arch, rendered in white fibreglass, was developed from an assemblage of bone and plaster that appears in the ‘Pigsty’. The artist altered his original design when it was enlarged, for both aesthetic and structural reasons, to open out more. The final form resembles both the arch of Stonehenge, and a simplified hip joint while the scale creates a dramatic surface where incised carving marks suggest monstrous claw marks, or ancient weathered stone. But it is the negative space that is highlighted out in the open air. Stepping onto the low plinth and entering into the arch, the form undulates overhead, highlighting the shifting sky around it. Much like on a visit to Stonehenge, it is physically walking among the forms that shifts the experience from interesting to captivating.

‘Henry Moore: Sharing Form’ is at Hauser & Wirth Somerset until 4 September.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has arts punditry become a perk for politicos?