From the September 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

During the reign of Sultan Husain Bayqara (1470–1506), Herat reached an apogee of cultural excellence. Descended from the Mongols, Sultan Husain embraced Shia, Sunni and Sufi beliefs; he encouraged poetry and scholarship and patronised extraordinary illustrators through his kitabkhana, a library, scriptorium and atelier. Sadly, his once magnificent complex north of the Old City lies in ruins: the British destroyed the site in 1885. Today, its neglected pathways are walked by furtive heroin addicts and Taliban soldiers sniffing out heresy.

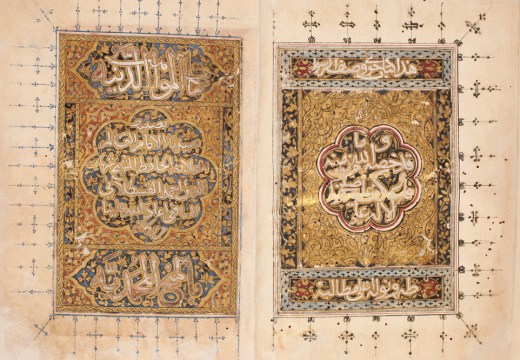

Something of that lost glamour can be glimpsed, though, in two astonishingly beautiful manuscripts that found their way from Herat to Mughal India and eventually the British Library. They illustrate the Khamsa or five books of the 12th-century poet Nezami Ganjavi, including the famous romances Khusrau and Shirin as well as Layli and Majnun. Barbara Brend, in her new book Treasures of Herat, calls the two works by their unwieldy British Library identification numbers: Add. 25900 and Or. 6810. For ease of reference, I shall refer to them respectively as (I) and (II).

Something of that lost glamour can be glimpsed, though, in two astonishingly beautiful manuscripts that found their way from Herat to Mughal India and eventually the British Library. They illustrate the Khamsa or five books of the 12th-century poet Nezami Ganjavi, including the famous romances Khusrau and Shirin as well as Layli and Majnun. Barbara Brend, in her new book Treasures of Herat, calls the two works by their unwieldy British Library identification numbers: Add. 25900 and Or. 6810. For ease of reference, I shall refer to them respectively as (I) and (II).

Though (I) was transcribed in the 1440s, most of the paintings were added 50 years later. One of them shows Shirin contemplating a portrait of Khusrau – a visage so absorbing that her handmaidens want it destroyed. Thus Nezami’s story of intoxicating love is used by the artist to highlight the tempting allure of painting itself. Brend believes that, contrary to earlier attributions, this is the work of the great Kamal ud-Din Behzad. She points to the dynamic, individuated faces of the handmaidens – you can almost hear them whispering – and the delicate pinkish rocks in the background. The face of Shirin, as in another illustration of her being spied upon bathing, was evidently painted over during the Mughal era to give her more Indian-like features. We can get an idea of what the original might have looked like from the same scene in (II) – a classical Chinese moon-face and arched eyebrows.

One of the most emotionally vivid illustrations in (I) shows the moment when Khusrau approaches Shirin’s castle on horseback. The artist sets the scene at night, the stars dotting the dark blue sky, adding in Brend’s words ‘a sense of romantic excitement’. Khusrau, flushed from his hunting exploits or perhaps shy, rides his piebald horse on to the silk carpet spread before him by Shirin’s welcoming retainer. On the balcony, three women look on: a lovelorn lady holding some wilting narcissi, another with her arm raised perhaps in anger and a third restraining her. Brend cannot decide which is Shirin and so speculates that each one represents an aspect of her divided soul. Ingenious, but far-fetched I think. To my eye, Shirin is clearly the lady with her hand raised, the gesture recalling that of Yusuf fleeing Zulaykha in Behzad’s most famous painting (also reproduced here). That’s also why I think Brend’s scepticism that this painting in (I) is by Behzad could be misplaced.

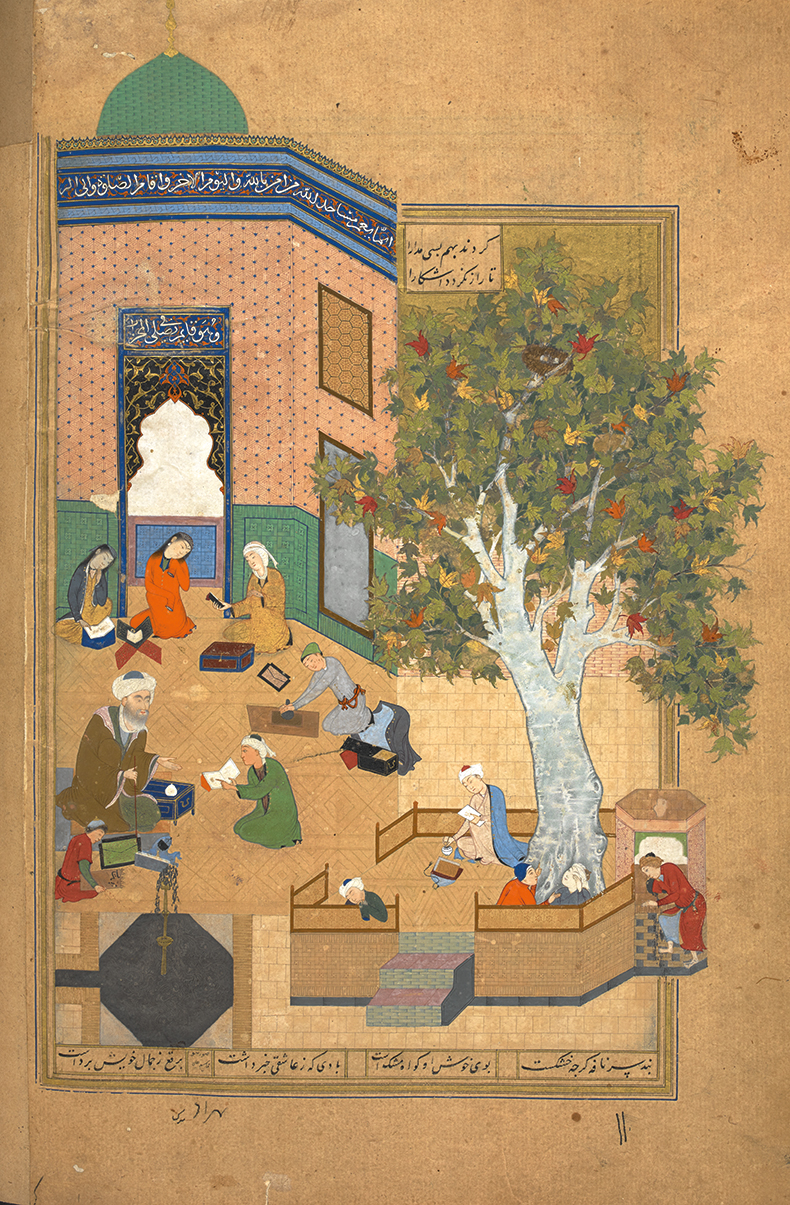

The images here are mostly of formal court scenes, ceremonies and battles. Some of my favourites, though, give us a peek at ordinary life. In (II), Qasim Ali, a pupil of Behzad, depicts the moment when Layli and Majnun meet at school. Before you spot them, the eye is drawn to the chinar or old world sycamore whose blooming green foliage is interspersed with fading red and yellow leaves. A youthful Majnun hands a book to Layli with an innocent air. (‘As one, they worked with many a careful sleight / In case their secret love might come to light.’) She is sitting in the prayer niche, an object of worship which obliquely reflects divine love. Around them the world carries on: a girl sits absorbed in reading; a young man dips his pen in an ink pot; a boy sleeps. Two livelier boys point to a birds’ nest in the tree, perhaps planning to shimmy up the trunk and steal the eggs. In a painting that tells the end of the story, Qasim Ali shows a forlorn Majnun embracing Layli’s grave while older women spin cloth, gossip or milk cows. About suffering, they were never wrong, those Heratis…

Layli and Qays at school from the Khamsa of Nejami Ganjavi (f. 106b from Or. 6810), (c. 1490), attrib. to Mirak and Behzad, but to Qasim Ali in the text panel, Herat. British Library, London Photo: © British Library Board

The Mughal emperor Babur provides the earliest criticism of Behzad. ‘His work was very delicate,’ wrote Babur in his memoirs. ‘But he did not draw beardless faces well; he used to greatly lengthen the double chin. However, he drew bearded faces admirably.’ The emperor’s discomfort at Behzad’s realism is exactly what we admire about him today. In his informal portrayal of Harun al-Rashid getting a haircut in the bathhouse, the caliph is topless except for brilliant blue trousers (echoed by the wave of blue towels hung up to dry.) Lacking the gorgeous robes by which the princes in these paintings are usually puffed up, he looks endearingly ordinary, as his barber tilts his head down to trim his locks.

For centuries these intimate images were gazed on by only a privileged few. Only now, with high-quality reproductions online and books such as this are they being opened up to the world. Who has the right to look was an idea these artists played with. A sensual portrayal in (II) of ladies bathing draws us in with its voyeuristic gaze – until we are arrested by the single eye of a man watching through a slit in the window, clutching the shutter in excitement. Is he a Peeping Tom or a Sufi getting a foretaste of heaven? Of course, he is both, as well as being a self-portrait of the artist: Mirza Ali inscribed his name above the man’s turban.

Both Mirza Ali and Behzad signed their paintings. And while attributions will continue to be debated, perhaps it’s time we stopped naming these manuscripts after their Western collectors, royal patrons or library serial numbers. For me, these two masterpieces should be known as the Books of Behzad and his school.

Treasures of Herat by Barbara Brend is published by Gingko Library.

From the September 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home