The Korean-American artist Do Ho Suh (b. 1962) is well known for the diaphanous architectural structures that he has been making since 1998. These depict the interiors of the places he’s occupied, the carefully measured rooms rendered with exactitude in jade green, pink, orange and blue polyester. Against the rigour of a space’s parallel lines, the fabric details, such as light fittings, doorknobs, toilets, sinks and fridges, sag like Oldenburg inflatables. As you look through the gauze, these features multiply to create a dream-like, virtual space that invites the eye to move through it simultaneously in all dimensions. ‘The space I’m interested in,’ he has said, ‘is not only a physical one, but an intangible, metaphorical and psychological one.’

Suh’s London studio looks out onto the canal, just around the corner from the Victoria Miro Gallery where he’ll be showing some of his new works next year (1 February–18 March 2017). These include a corridor that will take viewers on a journey through space and time via a selection of the rooms in which he’s lived since childhood, all joined to form a kind of multicoloured intestine of architectural features. Other pieces stack different rooms – from Seoul, London and New York, where Suh now has homes – one inside the other like huge Russian dolls. The exhibition will be the first presentation of his work in London since Staircase-III was shown at Tate Modern in 2011, and the most extensive since his Serpentine Gallery retrospective in 2002.

The walls of Suh’s studio are pinned with cyanotypes of architectural details from his fabric pieces – wilting door handles and light bulbs, captured as if by blue X-ray. On a table strewn with books and models is a crudely painted house made from a cardboard box, the chimney spouting a plume of tangled string, to which are tied the remains of balloons. The artist, who has a shaved head and wears round gold spectacles, which lend him a priestly air, explains that he made it for his young daughter’s birthday – the house, lifted by helium, revealed her cake. The idea of a house transported, Wizard of Oz-style, is a recurring feature of Suh’s work, which speaks of displacement and the ‘experiments with coexistence’, as he puts it, designed to address such feelings of estrangement.

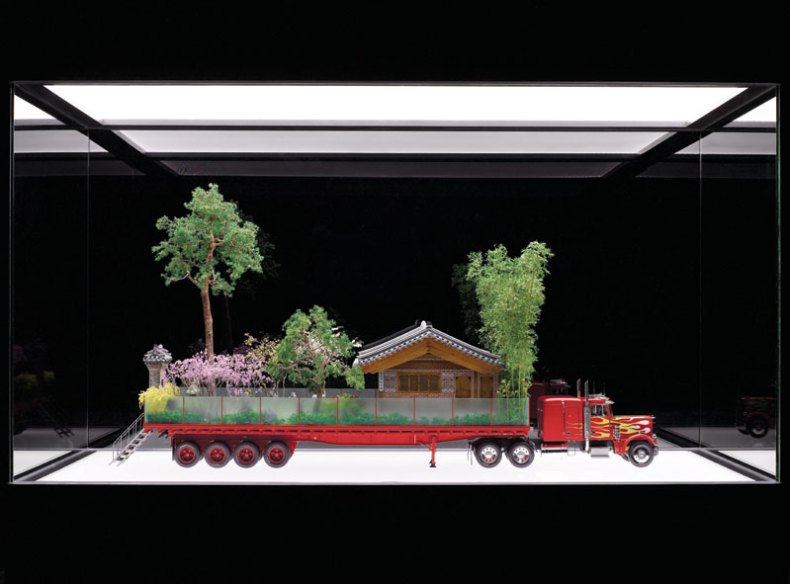

Seoul Home/Seoul Home/Kanazawa Home/Beijing Home (2012), Do Ho Suh. Photo: Jeon, Taegsu; © Do Ho Suh

One of Suh’s most important fabric pieces is Seoul Home/Seoul Home/Kanazawa Home/Beijing Home (2012), a recreation of his childhood home, a traditional Hanok house that appears in numerous works. Made from green silk organza (rather than the usual polyester), it is designed to be suspended overhead, like an oriental Tardis. It’s a ghost of the house built by his father, the influential painter Suh Seok, itself a copy of one built in the 19th century as part of Changdeokgung Palace, the royal residence in the centre of Seoul. King Sunjo wanted to experience the life of ordinary people, and had a scholar’s house built for this purpose in his compound, which is considered one of the most beautiful examples of traditional Korean architecture. One hundred and fifty years later, Suh’s father’s replica of the master’s quarters and library from the royal home was constructed from high-grade lumber salvaged from this complex, through which a road was built during the Japanese occupation in a systematic attempt to destroy Korean culture.

‘In many ways it’s kind of an unreal building,’ says Suh, whose parents still live there. ‘It’s an odd house in which to live in the 21st century. It was like living in a time capsule – it was a very idealised house right from the beginning. That’s the kind of sense of displacement I had every time I went out of the gate to go to school. I was living in a secret garden.’ The suspended form of his installation refers to the mesh mosquito nets under which Suh slept as a child, and also to the linen structures built inside houses during the three-year mourning period required in Korean culture. A meditation on self-imposed exile and loss, it was designed to be transportable, like clothing, so that Suh could recreate this intimate personal space wherever he was in the world.

The suspended form is reminiscent of a house-like blob that looms over and pursues a figure in one of Suh’s early drawings, entitled Haunting House (1999). ‘It’s a very ghostly house,’ Suh replies, when I make the comparison with his seemingly weightless installation, ‘always following or chasing me. I proactively try and bring my home with me wherever I go; that’s where the idea of making a transportable house in fabric came in. But maybe it’s been haunting me since the beginning.’

After graduating with a Masters in Oriental Painting from Seoul National University and completing his mandatory military service, Suh moved to Providence, Rhode Island in 1993 to follow his first wife, an American PhD student. He tells me that, having learnt English from a TV channel for American soldiers, which streamed Disney, he felt quite at ease with Western culture. However, he felt ‘uncomfortable’ in their new house, a large red brick building with a mansard roof that was divided into several high-ceilinged apartments, and first began meditating on the notion of home. ‘I tried to find ways to relate to myself in this new environment,’ he once said, ‘and that is how I began literally measuring space.’

Fallen Star 1/5 (2008–09), Do Ho Suh. Photo: Jeon, Taegsu; Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin Gallery, New York/Hong Kong, and Victoria Miro Gallery, London; © Do Ho Suh

‘In Korean architecture, there are lots of intermediate spaces,’ Suh elaborates. ‘You configure space in lots of different ways using screens, so the building is very porous, with little distinction between outside and inside. In America there was just total separation. Also there was no garden, so that was a very distinctive difference.’ In 2008–09 he created Fallen Star 1/5, a 10-foot-high model of this building, at a scale of 1:5, split open like a doll’s house or one of Gordon Matta-Clark’s architectural interventions. The details are dizzying (model-making was Suh’s boyhood passion): a fridge is cut in half, crammed with dissected contents such as a cabbage, carton of milk and mango. In a few rooms, the table is set for dinner, as though the house has suddenly been evacuated.

On the other side of this cross section, his wooden childhood home has smashed into the roof and façade, casting splinters everywhere and spilling Korean objects into his whitewashed American room. Suh plays down the violence of this collision of worlds, drawing attention to the parachute that has aided a soft landing. With its bunched-up green canopy, it’s a scaled-down fabric version of his Seoul home. The piece, he explains, was made as an illustration for a children’s book he planned to write, which has the Korean home lifted by a tornado and carried over the Pacific, to land on the house in Providence. There it slides into the centre, and starts to grow, ‘like a baby or a parasite’. ‘It could take over and consume its host,’ he adds. A three-dimensional printed translucent model shows this fertilisation, and glows a toxic green. It was intended as a parable of identity and belonging, with each miniature room lovingly recreated from memory.

The artist’s divided background is also explored in Bridging Home, his installation for the 2010 Liverpool Biennial, for which Suh wedged a Korean house, positioned at an awkward angle, between two buildings on Duke Street to create an image of domestic rupture. The traditional Asian house seems to have been uprooted by the Victorian buildings between which it is now squeezed. Another proposal for which Suh made intricate models was for a Korean home and garden to be transported on the back of a truck that would be driven from Seoul, via Alaska, to New York, where it would be deposited in Madison Square Park. For Secret Garden (2012), which celebrates the Korean courtyard space, Suh has created different scenarios in which the oriental garden either thrives or dies.

Secret Garden (2012), Do Ho Suh. Photo: Jeon, Taegsu; © Do Ho Suh

In A Perfect Home: The Bridge Project (2010), Suh created an architectural proposal for a bridge over the Pacific, which would have his ‘perfect home’ at the centre – an idea he has explored in several iterations and a project to which he says he’d like to return. One of these bridges from Seoul to New York is a Superstudio-like megastructure that carves unsympathetically through the landscape. Another design portrays a floating bridge, a biochemical construction that would grow organically as it’s carried north on the Pacific’s ocean current. As paper architecture, they serve like wormholes collapsing spatial differences between the East and West.

Suh had once dreamed of becoming an architect, and considered enrolling at Cranbrook in Michigan, a progressive architecture school that has no curriculum or courses. However, based on stories from his younger brother who is a practising architect, he was put off by the idea of having to work with difficult clients. ‘I’m no longer interested in building something completely new,’ he says. ‘I’m interested in digging history, or untold stories, from behind the walls. Using the space as a means to understand the path of my life and the time I’ve spent there. Most of us are just passing through these buildings, and I’m very aware of all the others who have lived there before.’

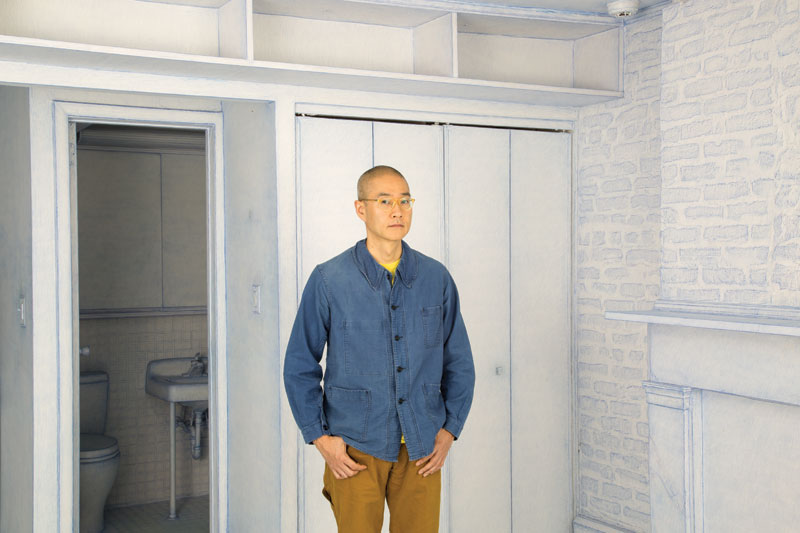

He is about to finish a three-year project, which has seen him wrap in paper the entire interior of the house in which he has lived for the past 20 years in Chelsea, New York. It is a building that Suh has already explored in his fabric sculptures, such as Apartment A, Unit 2, Corridor and Staircase, 348 West 22nd Street, New York, NY 10011, USA (2011–14), with its red staircase that zigzags through the building. Now he and his four assistants have rubbed almost the entire space in pencil or pastel, an act of frottage that records the grain and texture of every surface. Suh’s landlords, a couple who were both psychoanalysts, invited him to extend the project from his own apartment to all three stories of the brownstone, and now they’ve passed away he’s rushing to complete it before the building is sold.

‘It’s opaque,’ Suh says of the effect that results from the rubbing, ‘and it’s really interesting because lines on the edges of the walls and objects are emphasised, so it looks like a line drawing – almost like a cartoon. It flattens the depth of the space a bit, so it oscillates between a two-dimensional drawing and a three-dimensional space. It drives you kind of crazy, and you also see the pencil strokes. You’re in the drawing basically.’ Indeed, the spaces that he’s already assembled, such as Rubbing /Loving Project (2013–14), look quite uncanny. The thin glue he uses to wrap the surfaces picks up the dirt on the walls in the process of rubbing, which brings out the textures on the verso.

In the 1980s the Swiss artist Heidi Bucher embalmed her own family home in this way (Ancestor’s House, 1980–82). She skinned the interior in latex, which she moulded around its architectural features, in the process stripping them of all patina and dust. The house was a container of memories, and her reconstructed, sagging rooms were fragile portraits of absence and loss. Similarly, Suh’s project is, in a way, an act of mourning; not only for his imminent eviction, but also for his late landlord, a man he describes as his ‘American father’. The project might be interpreted as an act of Oedipal fidelity. When he wrapped the office his landlord used for his psychoanalytic practice, the room was completely white – a vision of startling erasure.

Suh is totally absorbed in this work, describing the project as an almost spiritual quest. ‘It’s gone beyond art,’ he says. ‘You live in and through the project, literally and figuratively.’ The building used to be a German sailor’s dormitory, and he keeps thinking about all the people that have been in that space. ‘I’m just one of them,’ he says. He is about to return to New York for a final burst to finish the piece. ‘I wish we could have met there,’ he says. ‘That’s what architecture means to me at the moment.’

‘The walls behind the paper are starting to talk to me,’ Suh says. ‘I’m reliving 20 years of time.’ As he was crawling through the house, vigorously rubbing every corner, crack and protrusion, Suh remembered a visit to a wise man a decade ago. He told him that, in a previous life, Suh had been a Tibetan Buddhist monk, and he described his climbing to the top of the Himalayas, pausing along the ascent to polish and rub all the rocks and boulders in his quest for enlightenment. Suh is astonished by the analogy: ‘I realised that I’m doing exactly the same thing.’

From the November issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home