Wentworth Woodhouse in Yorkshire, the longest if not the largest country house in England, has been a problem ever since the late Manny Shinwell, Attlee’s Minister of fuel and power, in a one-sided skirmish in the class war, ordered its park to be dug up for open-cast coal mining shortly after the Second World War. The Fitzwilliams gave up the house soon after that and, as it was then far too much for the National Trust to take on, it became a teacher training college. Two subsequent private owners lacked the resources to maintain let alone restore this monster of a house, which has a principal façade some 600 feet long and contains 365 rooms. Shorn of most of its estate, which is located not far from Sheffield, until this year its future seemed bleak.

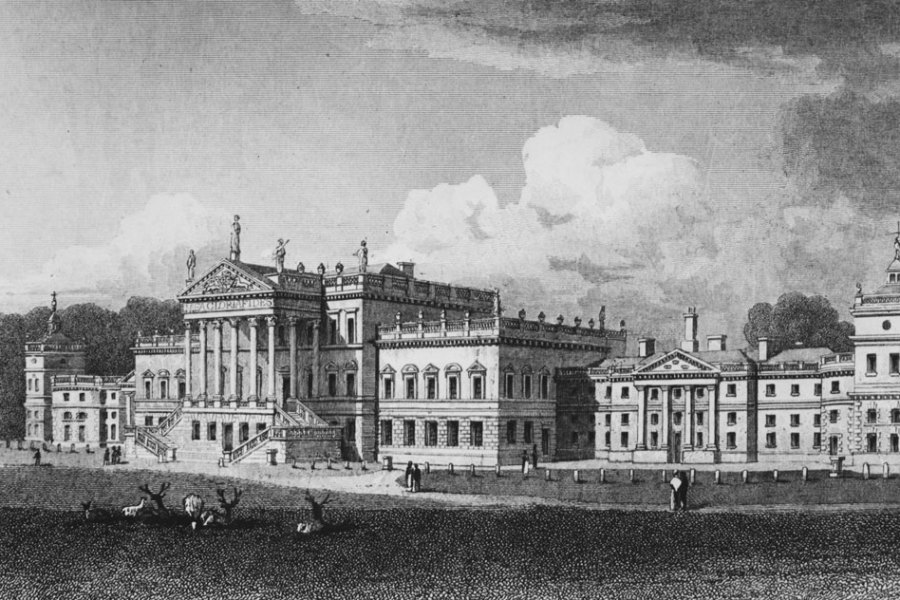

Its architectural history is complicated, but essentially Wentworth Woodhouse consists of two large country houses placed back to back, both built in the early 18th century by the same man, Thomas Watson-Wentworth, later the first Marquess of Rockingham. The first house, facing west, was a remodelling of 1725–34 of an earlier house. This building is vigorously and happily Baroque, described as ‘gay and profusely decorated’ by Nikolaus Pevsner, who thought it influenced by Austria and Bohemia. The second house, more a long screen facing east, was begun in 1734 and reflects a lamentable shift in taste. Inspired by Wanstead in Essex, the first great Palladian mansion in the country, its centre, with a grand Corinthian portico, is 19 bays wide, flanked by lower ranges of 11 bays each, with pavilion towers beyond. Impressive in ambition, it is also tediously repetitive and suggests how uncritical was the British devotion to Palladianism and the architectural prejudices of Lord Burlington.

The east front of Wentworth Woodhouse. Country Life © Country Life

What now makes the future of Wentworth Woodhouse viable is the practical business sense which characterises many of SAVE’s projects: the north wing will be used for events; the stable court for small businesses while conversion of parts of the building into flats and homes will bring in necessary income. As for the great state rooms – the Pillared Hall, the Marble Saloon, the Statuary Room and the rest – described by Pevsner as ‘of a quite exceptional value… not easily matched anywhere in England,’ they will be open to the public in partnership with the National Trust.

North Western aspect of Wentworth Woodhouse, in November 2003. Photo: Jeff Pearson, geograph.org.uk

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home