Nature is, according to Vivian in Oscar Wilde’s ‘The Decay of Lying’, a product of art. Fogs, for instance, only appear to the eye once they have been made the subject of paintings. ‘To whom,’ Vivian asks, if not to the Impressionists, ‘do we owe the lovely silver mists that brood over our river, and turn to faint forms of fading grace curved bridge and swaying barge?’ One answer that could have been offered (and indeed perhaps an example Wilde had in mind given his long-standing interest in and friendship with the artist) was James McNeill Whistler, the subject of a new, extensive exhibition at Compton Verney. Whistler’s (at the time) controversial paintings of the 1860s and 1870s, such as Nocturne: Blue and Gold – Old Battersea Bridge (c. 1872–75), which sadly is not on show, and Battersea Reach from Lindsey Houses (c. 1864–71), which is, established the artistic priorities of Impressionism on the banks of the Thames. ‘Whistler and Nature’ traces the aesthetic possibilities the artist discovered in the structures and mechanisms of economic productivity – barges and bridges, warehouses and wherrymen.

Battersea Reach from Lindsey Houses (c. 1864–71), James McNeill Whistler. The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

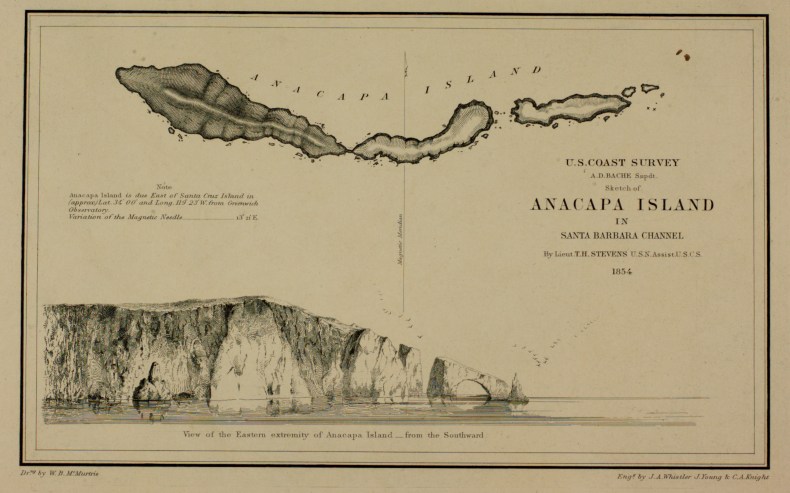

One of the results of this approach is that it allows the curators to introduce generally neglected aspects of Whistler’s early life and artistic training. In spite of his insistence that ‘neither Chemist nor Engineer can offer new elements of the Masterpiece’, Whistler was from a family of successful railway and marine engineers, and his own life and career looked for a time like it might also develop in this direction. He was trained as a geological surveyor and map-maker at West Point; following his ejection on the grounds of deficiencies in chemistry and ‘recurrent breaches of discipline’, he was employed in the drawing department at the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey.

Anacapa Island (1845), James McNeill Whistler. The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

Two of Whistler’s technical drawings from this period are extant; both are on display here. Their synoptic precision provides valuable context, not only for his early, razor-sharp etchings of London, but for later coastal works such as Harmony in Blue and Silver: Trouville (1865). The musical aspirations of Harmony’s title emphasise abstract and formal qualities – as Whistler put it, ‘Divesting the picture of any outside anecdotal interest which might have been otherwise attached to it’ – thus encouraging it to be viewed first as an ‘arrangement of line, form and colour’. But it is the comparison with Whistler’s surveyor’s diagrams that enables a reconsideration of both his interest in the aesthetics of abstraction and a new way of seeing 19th-century techniques of objectivity.

Limehouse (1859), James McNeill Whistler. The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

Throughout this exhibition, visitors are invited to consider what might be involved in thinking about a landscape, a sketch, a portrait as straightforwardly natural. This is especially true of later sections of the show, which concentrate on Whistler’s sketches and lithographs of female figures. A series of pictures of Whistler’s wife Beatrix gardening are paired in the gallery with sketches of dancers with diaphanous garments blown aloft by a mechanical fan (an arrangement devised by Albert Moore). Taken together, these pictures help to establish what the curators refer to in the catalogue as ‘Whistler’s urban vision of nature’ – most literally through their documentation of urban gardens, but also in his experimentation with the ways in which the appearance of natural embodiment and movement might be arrived at by studiously artificial means. These sections of the exhibition risk, however, surrendering some of the nuance achieved elsewhere. Claims for Whistler’s interest in nature as a space of economic productivity are less straightforwardly applicable to these pictures. Equally, placing gardens (urban gardens included) or female nudes in the context of naturalness risks reinstating well-worn assumptions about both nature and gender that, elsewhere, the curators seem intent on undoing.

La Sylphide (c. 1896–1900), James McNeill Whistler. The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

Whistler’s abhorrence of nature’s chaotic slovenliness in comparison with the artist’s creative power ‘to pick, and choose, and group’ was often stated. This makes ‘Whistler and Nature’ an almost perverse act of resistance to the artist on which it concentrates, as the curators themselves hint. But at its best, this exhibition convinces the visitor of the value of this approach, animating Whistler’s work with the suggestion not just that nature is the covert subject of his most interesting art, but also that nature was always for him artificial.

‘Whistler and Nature’ is at Compton Verney, Warwickshire, until 16 December.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home