Gigantism is a phenomenon of our age – and not only in land-art projects outside the gallery walls. Ai Weiwei’s current Law of the Journey installation in the National Gallery in Prague, for one, offers as its centrepiece a 70m-long lifeboat filled with 258 inflatable figures. Moves are afoot, however, to remind the public and the collector that small may be beautiful after all. The latest addition to this month’s London saleroom calendar is Actual Size, a curated evening sale encompassing any work of art that may be reproduced life-size on a single page of a catalogue (with an exception or two made for works that spill over onto a double-page spread).

Thomas Bompard of Sotheby’s London says of the 21 June sale: ‘I wanted to break the addiction, the belief that has developed in the art world in recent years that bigger is better. We may be impressed by something that is big but it is the small-scale and intimate that touches us. A sense of connoisseurship is more obvious in small-scale items – and the quality is likely to be better too.’ Another obvious benefit for collectors is that these works of art also take up significantly less space.

Concetto Spaziale (1966), Lucio Fontana. Sotheby’s London: estimate £250,000–£350,000

Indeed, the likes of the diminutive Concetto Spaziale of 1966 by Lucio Fontana – a bumpy ovoid of glittering metallic shards punctured with holes and set on a gold ground like a quattrocento painting – is, almost literally, a gem. ‘L’Oro è bello come il Sole!’ said the artist. It is impossible not to want to pick it up. This is a small piece with vast ambition – the contemplation of the infinite void. Measuring just 15cm by 10cm, it is expected to fetch £250,000–£350,000.

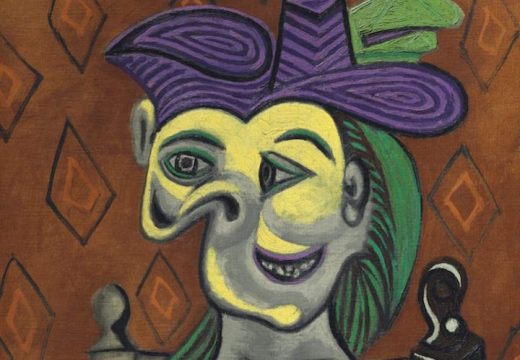

Among other highlights is an even smaller, Rose-period Picasso ink on paper, Femme Assise, executed in 1906, depicting a figure that exhibits all the poverty, loneliness and despair of the artist’s wretched laundresses (estimate £800,000–£1.2m). Pino Pascali’s Bomba a mano of 1967 is, according to Bompard, the only readymade of the Arte Povera movement (£200,000–£300,000). Here, the artist has removed the grenade’s detonator and substituted a handwritten note. As the critic Anna D’Elia has written: ‘The political gesture is in the paradox: offering weapons that don’t fire in order to disarm war.’

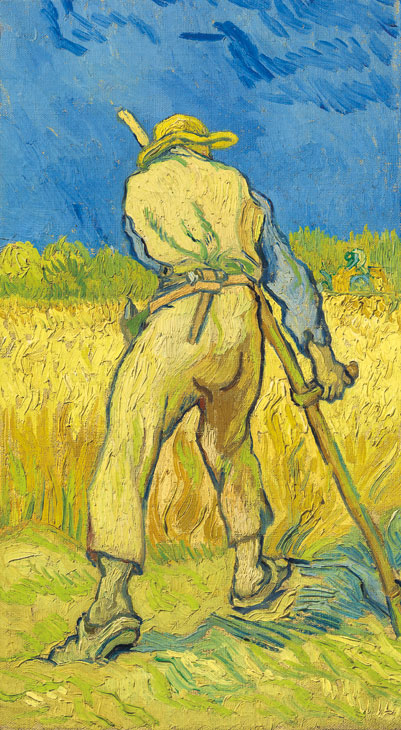

The commanding presence of Van Gogh’s Le moissonneur (d’après Millet) also belies its mere 43cm height. This tour de force was last seen on the market in 1995 when it was acquired by a UK collector, and it now comes to Christie’s London on 27 June with an estimate of £12.5m–£16.5m. Here, the intensity of colour leaps from the canvas, while its subject, a solitary and boldly delineated reaper, is rendered monumental as he works silhouetted against the bright sky. During his voluntary stay at the asylum in Saint-Rémy over the autumn and winter of 1889–90, Van Gogh painted 10 works inspired by a set of engravings by Jean-François Millet – an artist he much admired. Although in one sense close copies, Van Gogh saw them more as translations into another language, ‘the one of colours, the impressions of chiaroscuro in black and white’.

Le moissonneur (d’après Millet) (1889), Vincent Van Gogh. Christie’s London: estimate £12.5m–£16.5m

While Van Gogh saw his earlier sower and wheat sheaf – also after Millet – as representing eternity, he saw in the reaper and his scythe the image of death. ‘But there is nothing sad in this death, it goes its way in broad daylight with sun flooding everything with a light of pure gold,’ he wrote to his brother. Theo replied that he thought these paintings after Millet were perhaps the best things Vincent had yet done.

Buildings rather than people offer the metaphor for mortality in Schiele’s emotive Einzelne Häuser (Häuser mit Bergen), another of the highlights in the Christie’s London sale. In this wartime painting of 1915, the subject is his mother’s hometown of what is now Český Krumlov in the Czech Republic, a place from which he and his mistress, Wally, were driven by a community outraged by their non-attendance at church, their ‘living in sin’, and his rumoured use of naked young girls as models. In this canvas, the topsy-turvy houses of this ‘dying’ medieval town stand huddled and vulnerable, isolated in a barren landscape that similarly offers its inhabitants no solace. These buildings are rendered as febrile, awkward and near skeletal as the wretched naked figures and withering flowers that the artist also painted. His interest in Japanese prints is also evident in the schematic, layered landscape. The painting now returns to auction with roughly the same estimate as that accompanying its last saleroom outing in New York in 2006, where it achieved $22.4m. Expectations are £20m–£30m.

There is melancholy but also a stillness and poetry pervading the interiors of Vilhelm Hammershøi. During the near decade (1898–1909) that he lived in the apartment at Strandgade 30 in Copenhagen’s old mercantile district, the artist painted about 60 interiors, many of which were – and remain – his most sought-after works. Some include his wife, Ida, or occasionally furniture or paintings, but the real subjects are the spare and endlessly reconfigured geometries of the largely empty rooms themselves, and the soft infusion of light that treats the muted tones of walls, floorboards and shimmering white doors.

White Doors was one of the earliest of 15 variations on the theme of door and window, and now makes its auction debut at Sotheby’s London on 6 June. It had been acquired from the artist by the art critic and satirist, Axel Henriques, and passed to his daughter and then to his grandson, the Danish American furniture designer, Jens Risom. The painting comes with an estimate of £400,000–£600,000; Hammershøi’s current auction record is £2m.

The Martyrdom of Saint Victoria (1737), Nicolas-Sébastien Adam. Sotheby’s Paris: estimate €200,000–€300,000

Paris, like London, is busy this month. One of the jewels on offer in the French capital is Nicolas-Sébastien Adam’s plaster relief for his monumental bronze in the Chapelle Royale in Versailles. Representing The Martyrdom of Saint Victoria, this dramatic scene is infinitely more successful than the bas-relief there produced by his less talented elder brother, Lambert-Sigisbert. This high-quality plaster, patinated to resemble the finished bronze, was the modello presented to Louis XV and shown at the Salon in 1737. Another variant, in the Church of St Louis in Fontainebleau, which is smaller and executed in terracotta, appears to be the first preparatory study. Together the three works illustrate the process of invention, with the preparatory works – as is so often the case – rather more appealing than the finished bronze. It is expected to fetch in the region of €300,000 at Sotheby’s Paris on 15 June.

The main highlight of Sotheby’s London Ancient Marbles sale is the latest deaccession from Denver Art Museum. This powerful marble portrait bust of a Roman army officer is exceptionally well preserved, and dates from the second half of the 2nd century. It comes to the block on 12 June with an estimate of £300,000–£500,000.

From the June issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home