One of the most distinctive British painters working today, Matthew Krishanu creates emotionally layered, enigmatic and sometimes politically pointed works characterised by simple compositions and plain colour schemes. Paintings are his way of exploring subjects as wide-ranging as colonialism, grief and the history of art. The son of a British Christian father and an Indian theologian mother, Krishanu was born in Bradford and spent 11 of his childhood years in Dhaka, Bangladesh, as a result of his father being posted there for missionary work. Much of Krishanu’s work centres brown figures and conveys a tender sense of solitude, alienation or simple apartness. His latest exhibition, ‘The Bough Breaks’, is at Camden Art Centre until 23 June.

Where is your studio?

In Blackhorse Lane Studios, near Walthamstow. I’ve been there for more than 12 years now; I can walk there and back from home. There are two big south-facing windows so I get really good, strong daylight throughout the day – a raking light across all the walls as the sun moves. That would be too much for some artists but I like the way that direct sunlight on a work can illuminate areas of it and change the way you work while that happens. That’s one of the main reasons why I love the studio: it’s always felt like a real painter’s space and my work really benefits from daylight. Previous studios have just had portholes and a small skylight.

The size of the studio also allows me to work on multiple large works – often three metres wide or two metres high – at the same time.

What is the atmosphere like in your studio?

It’s very much a space I’ve made home for me. I feel very relaxed in the studio. The walls and floor and my painting clothes are all suitably paint-splashed, which immediately gets me into a painterly frame of mind. I don’t have studio visitors very often, except when a show is about to open. It’s a space for me to be, and to feel able to experiment without other eyes on the work.

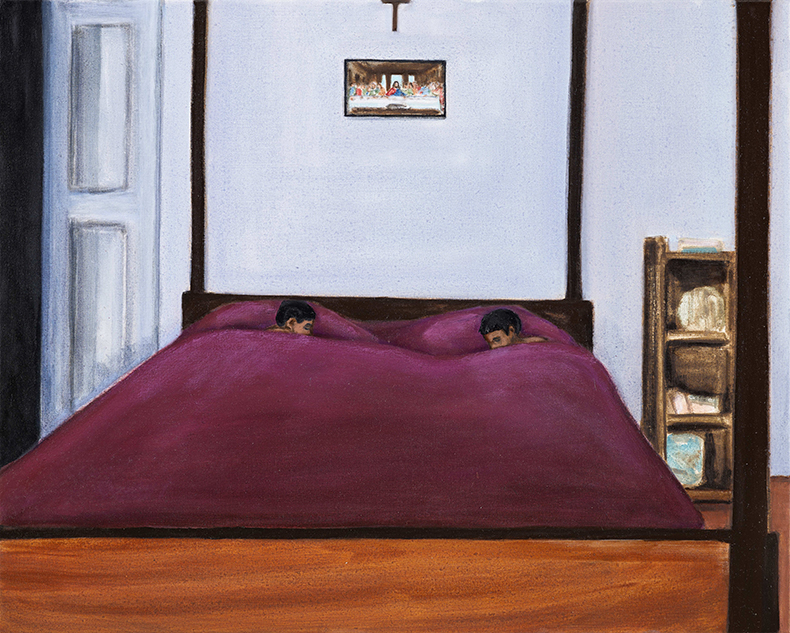

Bedroom (Last Supper) (2021), Matthew Krishanu. Photo: Peter Mallet; courtesy Tanya Leighton; © the artist

What frustrates you about your studio?

When you’re working on large canvases and flipping them around, the paintings hit the ceiling. You can feel a bit hemmed in. But it’s a balance: those vast warehouse or hangar studios can be a bit clinical.

My studio’s on the first floor, so getting work out of the building can be tricky. Everything needs to be on wheels. But these are just logistics – nothing to do with the quality of light or the things that really matter.

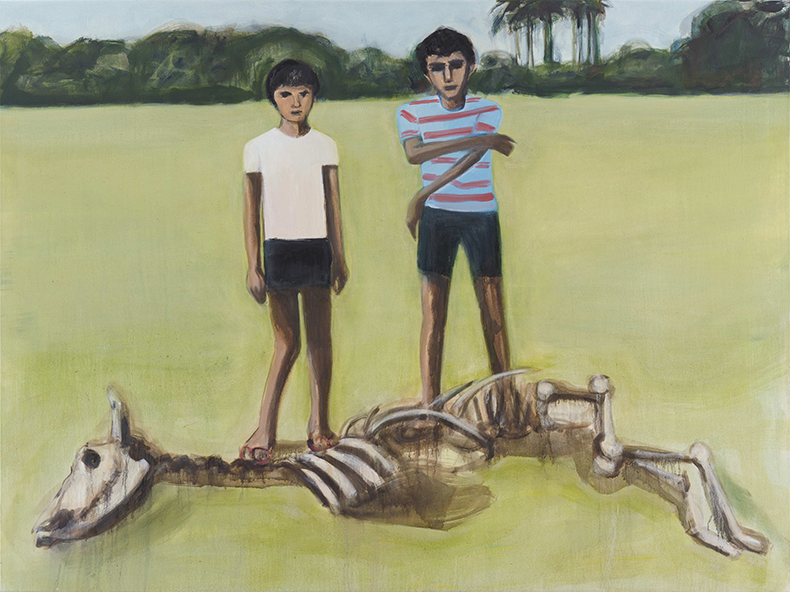

Skeleton (2014), Matthew Krishanu. Photo: Peter Mallet; courtesy Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London; © the artist

What do you tend to listen to, if anything, while you work?

When I get to the studio, I get into my painting clothes and put on music. I always have music that I want to paint to – it’ll be to do with mood and the energy I want to convey. If I’m painting a huge banyan tree, I will listen to something with a heavier beat. Rosalía’s recent album, for instance, I’ve had on quite a bit. Also Arca’s recent stuff, which is quite beatsy.

For mellower stuff I listen to Tricky, Portishead, Billie Holiday – stuff I listened to in my teens. I’ve been listening to PJ Harvey’s latest album, I Inside the Old Year Dying. I listen to FKA twigs a fair bit.

When I’m washing brushes, which can take up to an hour a day – I use a lot of brushes – I often listen to the news, and sometimes podcasts.

Banyan (Boy) (2023), Matthew Krishanu. Photo: Peter Mallet; courtesy and © the artist

Do you have a particular studio routine?

I work from Monday to Friday and paint around my daughter’s school hours. A few times in the last six months, because of this show, I’ve worked on weekends – when my daughter’s at an extracurricular club, for instance.

I love painting in the morning. On working days I get here for 9 or 9.30am; I’m here until around 3pm. When I start a new body of work it takes a little while to get into it, but once I’ve got a series on the go, I immediately know what I’m going to be painting. Once I’m in my painting clothes I lay out all my paints from dark to light tones, with a warm and a cool shade of each colour; I lay out the brushes by type; and I look at the painting and ask myself what it needs. I keep working until there’s nothing else it needs.

Because there are always many paintings on the go at the same time, I never get too hung up on any particular painting. I reject a lot of paintings as I go, for having the wrong composition or the wrong subject.

What’s the most unusual object in your studio?

I have some old Indian puppets, which used to belong to my late wife, that I call ‘puppet king’ and ‘puppet queen’. I’ve painted these puppets every so often over the last 15 years.

‘Puppet king’ and ‘puppet queen’. Courtesy Krishanu Studio

What is your most well-thumbed book?

There’s an El Greco catalogue that I’ve gone back to again and again since my B.A. more than 20 years ago. I do have books in the studio but I tend not to refer to them. More than any book I have a wall of print-outs in the studio, which is the most important visual resource for me. There’s a whole range of artists on that wall: Soutine, Rembrandt, Sofonisba, Sickert, Munch, Noah Davis, Joan Mitchell.

Who is the most interesting visitor you’ve ever had?

Bidisha Mamata, who is writing the File Note [one of a series of texts published by Camden Art Centre to accompany its exhibitions] for my show, came in recently, and we spoke for three hours. Bidisha is someone I’ve watched on TV and heard talk on Front Row and Saturday Review for decades. We had lots of conversations around being in the cultural industries and about my work and our place in Britain.

As told to Arjun Sajip.

Boy Swimming (2023), Matthew Krishanu. Photo: Peter Mallet; courtesy Jhaveri Contemporary; © the artist

‘The Bough Breaks’ is at Camden Art Centre, London, until 23 June.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home