This review of The Italian Renaissance Altarpiece: Between Icon and Narrative by David Ekserdjian appeared in the December 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

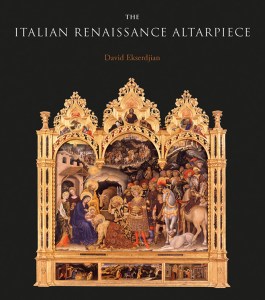

In the acknowledgements to this sumptuously presented and carefully argued book, David Ekserdjian alludes to its ‘almost demented ambition’. Over 400 pages and aided by 250 illustrations, all but a handful in exquisite colour, Ekserdjian attempts a comprehensive study of the altarpiece in Renaissance Italy. The field of enquiry is a distinguished one, reaching back to Jacob Burckhardt and with an ever-growing bibliography of increasingly specialised studies. Ekserdjian bravely pushes back against this trend by aspiring to an encyclopaedic overview of the genre, one which nonetheless preserves the nuance of the material and encompasses neglected centres to gain a more representative picture of the peninsula as a whole.

Even with a book of this scale, the scope of the endeavour entails choices. Some plates articulate wider architectural surrounds, and there is a valuable discussion of extended framing in Chapter 7, but the images are overwhelmingly of the artworks themselves (with a sprinkling of preparatory drawings). Here the author holds true to his own philosophy regarding what ‘matter[s] most in our profession: to have the chance to sit or stand in front of original works of art’. The exceptional visual apparatus of this volume allows the reader to replicate that experience in comfort, with Ekserdjian as their cicerone.

Even with a book of this scale, the scope of the endeavour entails choices. Some plates articulate wider architectural surrounds, and there is a valuable discussion of extended framing in Chapter 7, but the images are overwhelmingly of the artworks themselves (with a sprinkling of preparatory drawings). Here the author holds true to his own philosophy regarding what ‘matter[s] most in our profession: to have the chance to sit or stand in front of original works of art’. The exceptional visual apparatus of this volume allows the reader to replicate that experience in comfort, with Ekserdjian as their cicerone.

Lamentation with Saints Benedict and Remigius and Donors (c. 1360), Giottino. Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence. Photo: Peter Horree/Alamy Stock Photo

While introductory sections provide relevant liturgical and devotional context, the emphasis is avowedly on the works themselves. Adopting a taxonomic approach, much of the book is organised into iconographic sections, and a consistent theme is the balance between iconic and narrative elements signalled in the subtitle. One of Ekserdjian’s core concerns is the importance of narrative for altarpieces throughout this period. A key exchange comes at the start of Chapter 3, where the author dismantles Charles Hope’s oft-cited assertion that narrative was a marginal concern for painters and patrons of altarpieces (emphasising ‘people, not stories’). A wave of contrary evidence follows and by the chapter’s end few will dispute the judgement that ‘the narrative altarpiece was understood in those terms in the period, and is not the result of a subsequent misapprehension’. The range of narrative subjects pre-1600 is further confirmed by a dedicated appendix.

The discussion of narrative is part of a broader emphasis on continuities in function and subject matter across the three centuries surveyed. This study thereby provides an important corrective to the traditional stress in altarpiece studies on the linear development of the polyptych form and emergence of the rectangular pala. Instead, with the benefit of a wider chronological and geographic net, Ekserdjian delineates a much richer and more nuanced panorama. Telling echoes emerge, such as Pietro Lorenzetti’s Carmelite altarpiece as a distant antecedent of the tavola quadrata. Furthermore, the author argues persuasively that artists compensated for the demise of the narrative predella in the decades around 1500 by finding new ways to include narrative content in their unified-field altar images. In this and other ways, later pale and sacre conversazioni are reassessed as ‘polyptychs in disguise’.

Apparition of the Crucifixes of Mount Ararat in the Church of Sant’Antonio di Castello (c. 1515), Vittore Carpaccio. Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice. Photo: Bridgeman Images

What the reader will not find are any interior views or plans of churches, in contrast to the major regional studies in the field by Henk Van Os (for Siena) and Peter Humfrey (for Venice). Working within the parameters of a single city, both Van Os and Humfrey sought to relate altarpiece design to the broader church interior, and to explore and posit schemes that brought together multiple altarpiece commissions. The contrast between old and new could be a powerful generator of meaning and modernity – a process that Vittore Carpaccio seems to reflect on consciously when depicting his own altarpiece pala of the Martyrs of Mount Ararat alongside gold-ground polyptychs within the nave of the Venetian church of Sant’Antonio in Castello, sadly destroyed but recently reconstructed by Nathaniel Silver. The detail of Carpaccio’s meta-imagery also documents how altarpieces could benefit from very extensive outer frames (fresco in this case) to allow them to dominate an entire bay. Ecclesiastical interiors were usually to some degree competitive environments between patrons (for both pious and less pious reasons) and altarpieces were often designed to attract the eye at the expense of their neighbours.

Lamentation with a Carmelite Saint (1521), Ortolano. Museo e Gallerie Nazionali di Capodimonte, Naples.

The author delivers on his promise to include works from every Italian region, but, as one might expect from a scholar of Parmigianino and Correggio, Ekserdjian’s attention tilts towards the 16th century and the cities of northern Italy. It is refreshing to see paintings by Ortolano, Moretto da Brescia, Bramantino, Gaudenzio Ferrari and Pier Francesco Sacchi take centre stage in a pan-Italian survey. The welcome emphasis on the later material does necessitate some ironing out of scholarly debates when discussing the earlier period. Andrea De Marchi’s important work on elevated ensembles of images on beams is enthusiastically acknowledged but its ramifications are not always related to specific works of art. For example, Giottino’s Lamentation was recorded by Vasari on the rood screen of San Remigio in Florence. It may not always have been directly related to an altar, a factor that could help to explain some of the formal and iconographic idiosyncrasies that Ekserdjian highlights. Yet De Marchi’s latest research has revealed that Duccio’s enormous Rucellai Madonna of 1285 – an exemplary candidate for what Victor Schmidt has christened a ‘super icon’, elevated over a screen – was in fact installed over an altar in one of Santa Maria Novella’s transept chapels, perhaps initially as a provisional arrangement while the church was still being built. So, for every rule, an exception, reminding us of Joanna Cannon’s prescient reflections on the limitations of an over-rigorous application of typology.

Citing a wealth of examples that is unlikely to be surpassed, Ekserdjian’s text is certainly alive to the exceptions that emerge whenever one attempts to apply a rule of thumb. He brings a healthy scepticism to the contextual evidence of contracts and dedications on which art historians (this reviewer included) have come to rely. Contrary to the steady and occasionally reductive drift elsewhere towards function and context, the broad genre of the Renaissance altarpiece is triumphantly reasserted here as an arena for artistic creativity and experimentation.

This review of The Italian Renaissance Altarpiece: Between Icon and Narrative by David Ekserdjian appeared in the December 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home