Removed from its stretcher in 1955 so that the vast, unfinished canvas could be reused by her estranged husband Sir Thomas Monnington, the fate of Winifred Knights’ last painting, The Flight into Egypt (1937–), serves as something of a metaphor for her career. A gifted draughtsman, Knights (1899–1947) was a star student at the Slade School of Fine Art and the first woman to win the Prix de Rome. But despite this early success her career stalled some years before her premature death, her reputation falling into complete obscurity thereafter. In 1957, one of her most important paintings, The Marriage at Cana (1923), was eventually donated to the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Wellington, having first been turned down by both the Tate and the Fitzwilliam Museum.

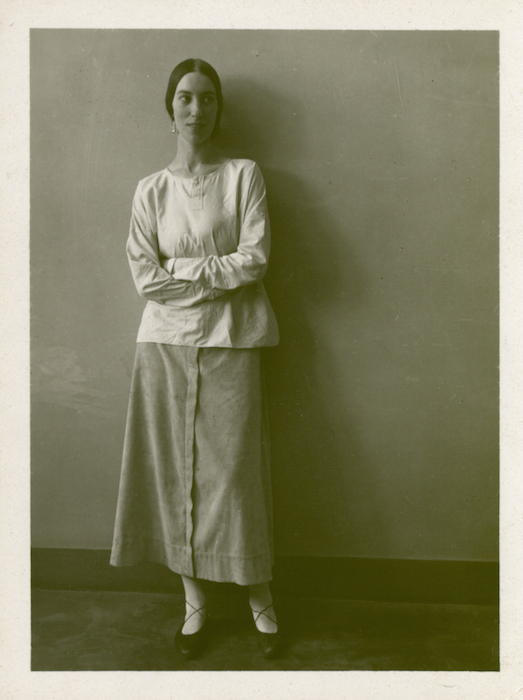

Photograph of Winifred Knights. © The Estate of Winifred Knights

Through drawings, paintings and sketchbooks from public and private collections, this exhibition provides a vivid encounter with an artist whose neglect seems all the more curious given the distinctive qualities not only of her work but of her personal appearance and character. Knights favoured a wide-brimmed felt hat and timeless clothes of her own design based on peasant costume and aesthetic dress. She imitated the flamboyant hairstyles of Renaissance portraits and her striking appearance clearly made quite an impact on those around her. Indeed, it is Knights herself whose self-portrait dominates the foreground of her only famous painting, The Deluge (1920).

Pausing to look back as she runs towards higher ground, Knights’ central figure anchors the diagonal thrust of the composition, which is echoed not just in the fleeing figures, but in the sharp lines of their shadows and the steep angle of the hill. While the figures are of a type, they are clearly identifiable as individuals, and include portraits of her mother and baby brother, sister Eileen and her aunt, the suffragette Millicent Murby. Fellow artist Arnold Mason appears twice and a preparatory drawing for the male figure at the top right of the canvas, bent double as he reaches for the top of the hill, is typically detailed, carefully but confidently drawn. The figure has been simplified considerably in the final painting, the back flattened and elongated to harden the lines and lend graphic impact while retaining the naturalistic vigour of the drawing.

Compositional study for The Deluge (1920), Winifred Knights. University College London. © The Estate of Winifred Knights

It is an arrestingly modern painting reminiscent of the Vorticists, but as the winner of the British School at Rome’s 1920 Scholarship in Decorative Painting, it had also to demonstrate Knights’ understanding of a tradition of monumental painting extending back to the Renaissance. Championed by Henry Tonks, the Slade’s legendary Professor of Drawing, Decorative Painting was a discipline that represented the pinnacle of the painter’s art, relying on Renaissance techniques and principles of colour, form and perspective to achieve a composition in keeping with an architectural setting.

Far from being anachronistic, Decorative Painting, with its emphasis on form, was regarded as a powerful riposte to modernism. Impervious to the assaults of post-Impressionism and Futurism, the principles established by the Old Masters were felt to be uniquely capable of tackling the challenges of the 20th century. For Tonks, The Deluge must have epitomised Decorative Painting: steeped in the mood of its time, its construction and even the treatment of figures are rooted in the quattrocento.

The painting’s biblical subject matter had become a familiar metaphor for the Great War, and while it is a theme traditionally associated with salvation, Knights’ treatment banishes all hope. Barely discernible in the nondescript background, Noah’s ark is more sinister than benign, sliding silently past as men, women and children flee the rising floodwaters. The inclusion of portraiture alludes to Knights’ own traumatic experience of the war but the painting reaches beyond the personal to offer a universal response.

The Marriage at Cana (1923), Winifred Knights. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. © The Estate of Winifred Knights

Despite sharing characteristics with The Deluge, The Marriage at Cana (1923), submitted at the end of her three-year Rome scholarship, achieves a very different mood. Once again space is sharply articulated but here repetitive vertical divisions and the play between interior and exterior space recall 15th-century Annunciation scenes, while muted colours and the quiet solidity of the figures, arranged in groups and across planes, show a debt to Piero della Francesca.

Compositional study for The Marriage at Cana (c. 1922), Winifred Knights. Private Collection. © The Estate of Winifred Knights

An exquisitely-made cartoon accompanied the submission and Knights chose to use egg tempera instead of oil paint: but this is no feebly anachronistic imitation. Occupying a prominent position in the foreground, Christ’s miracle is nevertheless obscured from view and by focusing our attention on the guests, Knights makes this a resolutely secular painting. Inspired by the formal dinners held at the British School at Rome, there is a strong sense of the languid tedium of these events, the pink of the watermelon providing a strange note of humour as one of the guests, fascinated by the spectacle of water being turned into wine, holds it to his mouth like a grotesque smile.

There is a sense that many of the lessons Knights learned from the Renaissance masters coincided with her own stylistic tendencies. Knights’ illustration for Little Miss Muffet (1918) portrays the artist herself in a notably graphic style, the vertical accents and elongated forms familiar from elsewhere in her oeuvre. The visual clarity and unfussy style that made her appear destined for a career in book illustration transferred well to narrative painting, and in The Potato Harvest (1918), made while Knights was evacuated to rural Worcestershire, she conveys the order and satisfaction of rural life, without sentimentality. Later on, this sense of harmony and balance is countered by visual and narrative tensions, her work becoming more complex, less illustrative, and far more interesting.

The Potato Harvest (1918), Winifred Knights. Private Collection. © The Estate of Winifred Knights

Knights’ greatest achievement was her originality. Even in Italy, Knights avoided romanticising what she saw, and never succumbed to pastiche. Primed by this long overdue introduction to a forgotten painter, we must hope now for a further exploration in which we see Knights in the context of her peers: only then will we be able to fully appreciate just how original she was.

‘Winifred Knights (1899–1947)’ is at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London until 18 September.

From the September issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home