Second Empire has become as much a moral as a stylistic label. In purely formal terms, there is no case for viewing the years 1852–70 as exceptional in the history of French taste. Flanked on the one side by Louis-Philippe, and on the other by the visual language of the nascent Third Republic, the arts in the 1850s and ’60s represent not so much a new departure as an intensification and multiplication of longstanding trends. But in moral terms, the Second Empire has been singled out for unique condemnation. The term conjures up a stubborn set of associations, linked to froth, greed, sex, and sumptuousness: from Offenbach’s giddy operettas to Cabanel’s yielding Venus; from Charles Worth’s couture to Emma Bovary’s misadventures; from the frenzied bustle of the Bourse to the gilded boudoirs of the grandes horizontales.

Rarely has the reputation of a regime been fixed so entirely by its adversaries. The republicans and socialists chased out of France after the coup of December 1851 took their revenge on Napoleon III in print. Thanks to Victor Hugo’s savage poems of exile, the last Napoleon (1808–73) has been dubbed ‘le petit’, a paltry impersonation of his illustrious ancestor. Disappointed liberals such as Alexis de Tocqueville lamented that France had fallen to despotism. The man described by Karl Marx as ‘an undecipherable hieroglyph’, a candidate for president who could stand for everything precisely because he stood for nothing, has been denounced for cynicism, brutality, and even proto-fascism. And the psychological flaws of the Emperor have been projected on to his regime, which has been judged as venal, ruthless and flashy, seeking to mask its inner contradictions under the glitz of the fête impériale.

View of the Grand Staircase at the Paris Opéra, designed by Jean-Louis-Charles Garnier (1825–98) and constructed between 1861 and 1875. Photo: Hemis; © Alamy Stock Photo

The implosion of the Second Empire on the battlefield of Sedan in September 1870, when the French armies suffered lightning defeat at the hands of the Prussians, has only intensified the suspicion that this was a society doomed to perish. In retrospect, the boisterous entertainment culture of the 1860s, with its costume balls and gaslit cafés-concerts, seemed to announce a headlong can-can over the precipice, a veritable galop infernal. The founders of the Third Republic were desperate to distance themselves from an old order that seemed stewed in corruption, and a political class accused of driving the nation to the brink of catastrophe out of bombast, hubris, and unhealthy feminine meddling. In the caricatures that proliferated after Sedan, the foreign-born Empress Eugénie was singled out for particular venom and accused of betraying French honour and peddling sexual favours to the Prussians.

The humiliation of 1870–71 prompted a search for scapegoats. In his Rougon-Macquart cycle of 20 novels, Émile Zola set out to dissect the sick tissues of the Second Empire. He found the perfect symbol of decay in the heartless and insatiable courtesan, Nana. The story of this precocious beauty, who used sexual charisma to rise from the streets, to the stage, to the conquest of wealthy male admirers, was a publishing sensation, selling 55,000 copies overnight when it appeared in 1878. Obsessed with documentary authenticity, Zola undertook substantial research into the demi-monde, and modelled Nana on famed courtesans such as Cora Pearl and Blanche D’Antigny. But according to Catherine Hewitt, another crucial inspiration came from the comtesse Valtesse de la Bigne, who despite appearances was the daughter of a linen maid from Normandy. A prostitute at a young age, she was a model for Corot and an actress for Offenbach; after taking the composer as a lover, she went on to win the attentions of prince Lubomirski and the prince de Sagan, acquiring in turn a title, a fortune, a palatial apartment, and a formidable reputation.

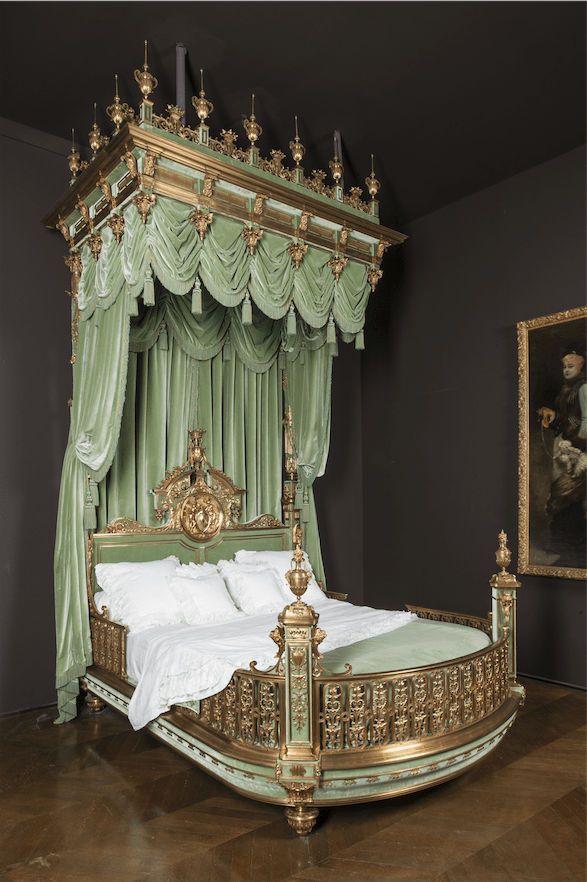

Comtesse Valtesse de la Bigne’s bed of state, c. 1875, designed by Édouard Lièvre. Photo: © Musée des Arts décoratifs.

Valtesse’s remarkable rise seemed to confirm that the upper ranks of the Second Empire had been infiltrated by parvenus; birth and merit now mattered less in determining status than guile and glamour. Zola’s own detailed inventory of Nana’s apartment – her delight in Persian rugs, Chinese cloisonné vases, Louis XIII armchairs, antique silver – derived from observations he had made in Valtesse’s home at 98 boulevard Malesherbes. He was especially taken with the hostess’s extravagant gilt-bronze bed, commissioned from Édouard Lièvre, the elaborate canopy of which was adorned with vases, grinning fauns, and a repeating ‘V’ motif, and swathed in green velvet. Zola made the bed the centrepiece of Nana’s boudoir: ‘utterly unique, a throne or altar where all Paris would come to worship her in her naked, equally unique, beauty’. For Zola, this ‘gigantic jewel’ of a bed embodied the sleaze and the sparkle of the Empire.

The political disgust felt for the Second Empire was thus transferred on to its material artefacts. A solvent of the social hierarchy, the regime stood accused of undoing aesthetic hierarchies too. Defenders of the academic tradition were disgusted by what seemed to be the degeneration of standards across the 1850s and ’60s into an eclectic free-for-all. Within the Salons the nobility of history painting seemed in full retreat before the irresistible rise of genre painting, in which archaeological exactitude and melodramatic gesture replaced moral instruction. The government’s curious blend of liberalism and authoritarianism in arts policy made it both unwilling and unable to stop the rot. The old quarrel between Ingres and Delacroix was not resolved so much as diverted when both were honoured with retrospectives in 1855. Far from trying to uphold standards, the notorious Salon des Réfusés in 1863 was a concession that the public could make up their own mind about the jury selection.

In this remorseless democratisation of judgement, the real victor was sensationalism. ‘It personified well the art of the Second Empire,’ wrote the man of letters and Parisian chronicler Jules Claretie in 1873, ‘that aphrodisiac art whose execution, this time superb, did not compensate for its vulgarity.’ This stinging reproof was aimed at Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s sculptural group La Danse, which had been unveiled on the facade of the Paris Opéra in 1869, and whose realism had so shocked its first viewers that it had been vandalised with black ink. ‘The truth is that it seemed to us of mediocre taste, and that the sculpture made a bawdy can-can out of the dance of the fairies.’

View outside the Paris Opéra of La Danse, 1865–69, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux. Opera Garnier, Paris, France. Photo: Jose Peral; © Alamy Stock Photo

If the Second Empire unsettled defenders of the tradition, it has also not been forgiven for neglecting the avant-garde. The struggle of rebels like Courbet and Manet against incomprehension and institutional exclusion in the 1850s and ’60s constituted the foundation myth of modern art. Their academic opponents were taxed with either the repetition of outworn conceits, or a penchant for titillation. ‘Today art has at its disposal only dead ideas,’ bemoaned Théophile Gautier in 1853, ‘and formulas which no longer correspond to its needs.’ Just as a self-consciously ‘new’ painting sought to break with the last lurid gasp of the academic tradition, so too the birth of ‘modern’ design was predicated on putting an end to the eclecticism in the decorative arts, which had created pieces of furniture of bloated dimensions, gaudy patterning, and shoddy manufacture. Second Empire taste soon became a shorthand for the stylistic baggage from which modernité had to emancipate itself.

It takes a brave institution to try and correct prejudices based on political, moral, and aesthetic disgust. The first serious attempt at rehabilitation, organised by the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1978, was still couched in apologetic terms; Jean-Marie Moulin, one of the curators (and then director of collections at Compiègne), was aware of the risk in celebrating a style viewed as ‘monstrous’, and which had invited ‘ostracism, sometimes even fury’. He added that the impetus had to come from colleagues in Philadelphia, for had the exhibition been proposed in France ‘it would have had great difficulty in seeing the light of day’. Post-war America had already been central to the wider rediscovery of French Salon painting, since Gilded Age millionaires had been among the most enthusiastic buyers of painters such as Rosa Bonheur, Jules Breton, and William-Adolph Bouguereau.

Rehabilitation in France has been a long time in coming. But this autumn the Musée d’Orsay will celebrate its 30th anniversary with the opening of ‘Spéctaculaire Second Empire: 1852–1870’ (27 September–16 January 2017). It marks the logical culmination of a number of recent exhibitions that have turned the spotlight on to once-reviled painters, not least ‘The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme’, which was shared between Paris, Madrid, and Los Angeles in 2010–11, and proved that his meticulous, quasi-cinematic canvases continue to be good box office. At the same time, it builds on pioneering exhibitions at the château de Compiègne – a favoured residence of the imperial court – which have explored the cultural scene under the Empire, including Émilien de Nieuwerkerke, the major-domo of arts administration. True to its title, the Musée d’Orsay show this autumn will draw not just on painting, but also on photography, sculpture, architecture, and the applied arts, to conjure up the phantasmagoria of imperial France in all its many guises.

Le Château de Pierrefonds , (c. 1868), Emmanuel Lansyer. Photo: Hervé Lewandowski; © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d’Orsay).

This reconsideration by curators has marched in step with a softening of critical opinion. The furious controversy that once raged around the status of l’art pompier now seems hard to fathom, even quaint. Art historians since the 1960s have so comprehensively eroded the boundary once presumed to separate the academy from the avant-garde that generalisations about ‘official art’ seem impossible to maintain. When Charles Baudelaire was fined for obscenity for Les Fleurs du Mal, a letter of entreaty to Eugénie saw the sum slashed from 350 to 50 francs and the poet was given philanthropic relief. Some of the richest recent monographs – such as Marc Gotleib’s study of Ernest Meissonier, the master of historical genre painting – have demonstrated the sophistication and reflexivity of painters who enjoyed commercial acclaim and court encouragement. Far from being a roadblock to innovation, the studios and Salons of the Second Empire fostered diversity and experiment.

With the narrow modernist canon blown open, the Second Empire can take its place as a proto-postmodern moment, the apogee of artifice and pastiche. The very qualities that once made the period anathema are today just as often designated as the secret of its allure: its profusion of references; its drama and flamboyance; its delight in novelty; and its unmatched feeling for display. The result was a medley of baroque theatricality, rococo luxuriance, Napoleonic grandeur, and even a foretaste of Las Vegas. ‘All modern French architects,’ observed Gustave Claudin in 1867, ‘spell out and vaguely dream of a style which one would be tempted to call the neo-Greco-Gothico-Pompadour-Pompeian’. The fullest expression of this fantastical architecture can be found in the gilded curves of Opéra Garnier, at its time the largest stage in the world, where spectators were fashioned into the spectacle. But a similar capriciousness in borrowing from the past can be found at the château de Pierrefonds, whose ruins were not so much restored as ‘reinvented’ by Viollet-le-Duc to provide a visionary medieval setting for the Emperor’s arms and armour.

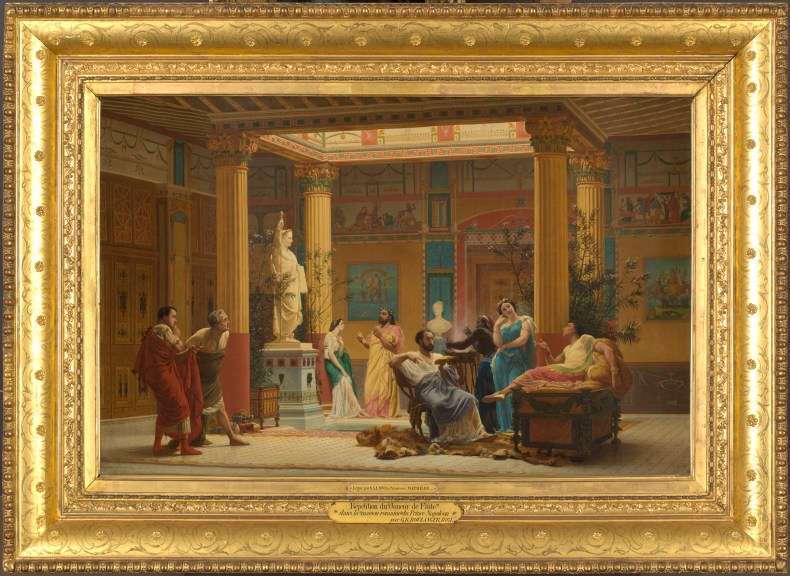

This blend of fantasy and modernity inspired private residences, too. Napoleon-Joseph Bonaparte – the cousin of the Emperor, nicknamed ‘Plon-Plon’ – ordered the construction of the Villa Diomède, or Maison Pompéienne, on the avenue Montaigne. The house was a testament to his passion for both classical archaeology and the classical actress, Rachel. It boasted an atrium, impluvium, trichinium, and xystos (colonnade). In Rehearsal of ‘The Flute Player’ and ‘The Wife of Diomedes’ (1861), a vibrant painting by Gustave-Clarence Boulanger, the toga-draped characters who fill the interior include the critic and poet Théophile Gautier, the playwright Émile Augier, and the actresses Madeleine Brohan and Marie Favart from the Théâtre-Français, gathered together in 1860 for a night of amateur theatrics. The programme for the performance claimed that the venue ‘had been closed for repairs for 1800 years’. The artificiality of their poses suggests a certain self-consciousness about this anachronistic Roman role-play. Boulanger was asked by Plon-Plon to copy the painting directly on to the walls of his house, setting up an antique mirror for his contemporary soirées. ‘Elegant modern fantasy on an ancient theme,’ noted Albert de la Fizelière in his Salon review. ‘The composition is up to the level of the setting, that is to say an ingenious, successful excursion into the realm of the past.’

The Rehearsal of ‘The Flute Player’ and ‘The Wife of Diomedes’ at the house of Prince Napoleon in 1861 , (1861), Gustave-Clarence Boulanger. Photo: Adrien Didierjean; © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d’Orsay).

But this emphasis on imaginative escapism should not detract from the very real institutional achievements of the period. The Second Empire left an enduring legacy at the Louvre, whose architectural reunification with the Tuileries palace was the accomplishment of a scheme dreamed of by Louis XIV and the first Napoleon. The monumental axis created by Visconti and Lefuel did not simply allow for the installation of magnificently ritzy state apartments; it also coincided with a number of fundamental donations – such as the medieval and Renaissance objects bequeathed by Charles Sauvageot in 1855, or the superb 17th- and 18th-century paintings left by Louis La Caze in 1869. Both donations were decisive in expanding the scope of the Louvre’s holdings, and both testified to the energetic embrace of amateurs championed by Nieuwerkerke. While some queried his credentials to be Director of Imperial Museums – beyond his liaison with Princesse Mathilde – ‘le bel Émilien’ undoubtedly brought fresh glamour to the Louvre, as commemorated in François Biard’s collective portrait. From his apartments in the Marengo wing, he organised during Lent the lavish ‘vendredis du Louvre’, which brought hundreds of aristocrats, officials, painters, musicians, and writers in a mingling of fashion, high society, and fine art.

While some may carp at the motives involved – a thirst for respectability, or crass speculation – private collecting came of age during the Second Empire. Through the enormous largesse of the Civil List – as studied by Catherine Granger and Alison McQueen – the court provided commissions for hundreds of artists and artisans. Leading Bonapartes and Bonapartists, such as half-brother of the Emperor, the duc de Morny, as well as Princesse Mathilde and Plon-Plon, ploughed their fortunes into building up private galleries (and armouries in the case of Nieuwerkerke). Those who helped bankroll the regime’s railways and commanded its factories, such as the Rothschilds, Achille Fould, Eugène Schneider, the Pereire brothers, were also distinguished collectors – even if, in some cases, the Old Masters were acquired and passed on with remarkable haste. The Second Empire saw the creation of a new entrepôt for buying and selling art, with the hôtel Drouot opening its doors for business in 1852. But it also stimulated the vogue for exhibitions, communicating artworks both virtually and physically before a mass public.

The artistic richness of the regime has been lost due to the circumstances in which it unravelled. Prussian bombardments in 1870 flattened Saint-Cloud, while the fires of the Paris Commune torched the Tuileries, wiping out two key monuments to Second Empire taste. The Rothschild château de Ferrières survived appropriation by Bismarck – indeed, the armistice was signed here – only to have its contents looted by German troops in the Second World War. Many stalwarts of the regime fled into exile after 1870, and took their cabinets with them, seeking to dispose of some of their treasures through the London salerooms. Hence the discrepancy between the relative paucity of Second Empire ensembles left in France, and the fine specimens that remain in Britain: the cabinet of the desperate, refugee Nieuwerkerke was sold to Richard Wallace in 1871, and so can now be visited in Manchester Square; the neo-rococo furnishings made by the firm Monbro fils âiné for John and Joséphine Bowes, when they were living in the pavilion at Louveciennes, were relocated to Barnard Castle; and of course there is the domed mausoleum erected to Napoleon III and the Prince Impérial at Farnborough by Gabriel-Hippolyte Destailleur.

The Second Empire was undoubtedly a time of transition, defined by unreconciled tensions. But this multiplicity and inconsistency is integral to its fascination. If we look beyond the polemics of the republicans, or the enmity of the artistic refusés, we will find the period fertile with new developments. Whether it be colonial entanglements in Southeast Asia, and the first stirrings of japonisme; or the celebration of industrial techniques, such as galvanoplasty and aluminium plating; or the rediscovery of native craft techniques, such as Claudius Popelin’s painted ‘Limoges’ enamels: the political dead-end of the Second Empire should not conceal its generative power across many artistic domains. It is high time for a more nuanced reappraisal of what the soldier, diplomat and journalist the comte de Maugny recalled as those ‘eighteeen years of luxury, pleasure, recklessness and gaiety […] those poor years of corruption’.

‘Spectaculaire Second Empire: 1852–1870 is at the Musée d’Orsay, Paris, from 27 September–16 January 2017.

From the September issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home