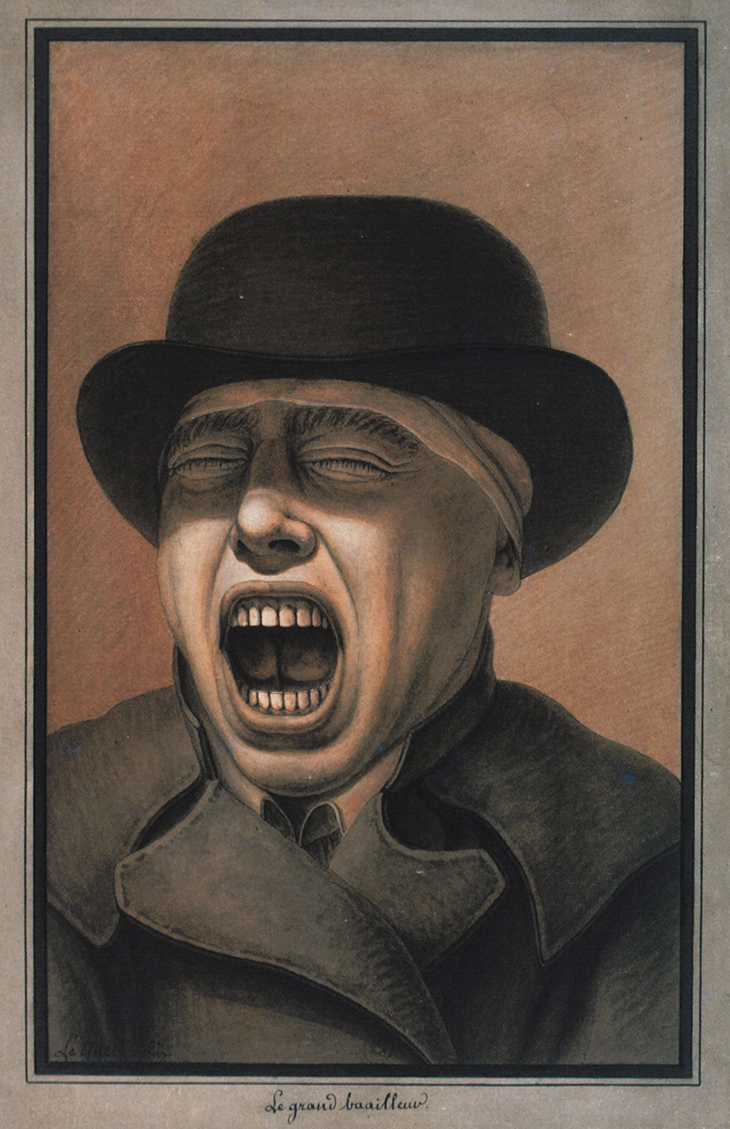

Five powerfully strange self-portraits open this exhibition about the fantastical French architectural draughtsman Jean-Jacques Lequeu (1757–1826). In each he has distorted his face into a grotesque mask, while retaining an unsettlingly direct openness with the viewer. In one a wide yawn is more like a silent scream, in another his face is contorted into a fishy grimace, while in a third he puffs his cheeks into a goggle-eyed parody of surprise. There is a degree of play-acting here, signalled by the different costumes Lequeu is wearing, but there is also something unnerving about their intensity and radical lack of vanity. We seem to be dealing with someone dangerously unhinged. It was these uncanny qualities that fuelled the rediscovery of Lequeu in the 20th century, when he was proclaimed as a proto-Surrealist and hailed as a disrupter of our notions of the period’s neoclassical politesse. Lequeu had deposited his drawings at the Bibliothèque nationale de France in 1825, like an architectural time bomb, before dying in obscure poverty. In 1987 the Lequeu scholar Philippe Duboy, with postmodern naughtiness, even went as far as to suggest that in the intervening years they had been tampered with by Marcel Duchamp.

The Great Yawner (n.d.), Jean-Jacques Lequeu. Biblothèque nationale de France, Paris

The central argument of this comprehensive exhibition is that to understand Lequeu through such ahistorical, psychoanalytic approaches is to do him a disservice. It attempts to ground Lequeu in his turbulent era, showing how his preoccupations, however bizarre they look to us, were shared by his contemporaries. His radical peculiarity is not a reflection of a deranged mind, but of his troubled, revolutionary times. So, for example, the self-portraits are explained through the contemporary interest in physiognomy and a widespread rejection of the narcissism of the ancien régime’s portraiture. Similarly, the architectural fantasies for which Lequeu is most famous are understood through pan-European trends in 18th-century garden design, and as sly comments on concurrent architectural and intellectual culture.

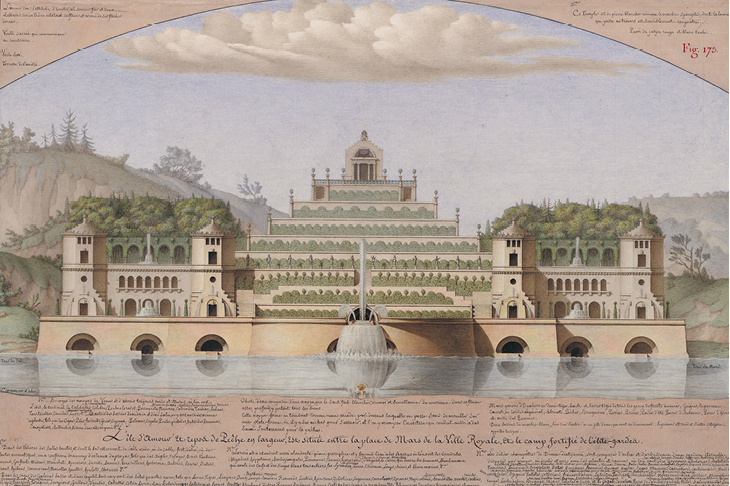

The historicising approach helps us focus on Lequeu’s dazzling mastery as an architectural draughtsman. He started his career in the office of Jacques-Germain Soufflot, architect of the Panthéon, and after the Revolution became the head draughtsman for the Commission of Public Works. In neither role was he given the responsibility to build any of his designs, but this allowed his imagination free rein, untethered by practicalities. His style as a draughtsman is distinguished by a meticulous attention to detail, and a wonderfully precise application of ink washes to create enlivening shadows. A beautiful drawing of the artist’s stationery from 1782 is typical of his perfectionism.

These are drawings to get lost in, and there is a pleasure in peering closely and discovering the odd details among the minutiae of his architectural jamborees, like a cracked version of Where’s Wally? Here is a cat on a cornice, there a dairy festooned with udders, elsewhere a couple are having sex in a hammock. If the exquisitely rendered detail is the chief joy of the drawings, its excessive application helps to account for Lequeu’s failure as an architect. Lequeu had an impressive stylistic range, but whether he is imagining chinoiserie pavilions, primitive huts, neoclassical temples, cliff-hewn grottoes, Egyptian halls or gothic castles, there is an obsessive piling on of minutely observed detail, often charged with obscure hermetic symbolism. It is this maximalist horror vacui that separates Lequeu from the stark classicism of those other utopian French architects Claude-Nicolas Ledoux and Étienne-Louis Boullée, with whom he is sometimes grouped.

Elevation and Section of a Temple for Equality in the Garden of Philosophy (1794), Jean-Jacques Lequeu. Biblothèque nationale de France, Paris

Despite their technical perfection, and after the initial thrill of their wacky originality and flagrant disregard of structural facts, the cumulative effect of Lequeu’s architectural fantasies is overwhelming and claustrophobic. If we are to see these drawings as more than a psychotic melange, rather as an expression of a turbulent historical moment, the key question becomes what Lequeu’s relation was to the French Revolution. The evidence presented by the exhibition is equivocal. Was Lequeu retreating into fantasy as a refuge from a frightening political reality, or leaping into untrammelled possibilities sparked by a moment of unprecedented change? The skeletal biographical details give little guidance. The recycling of a design for a Temple to Equality, a giant globe held up by busty caryatids, as a chapel dedicated to St Louis after the Restoration seems to demonstrate a certain ideological flexibility. The exhibition also presents enigmatic evidence for the crucial question of how far his architectural fantasies are knowing pastiches of architectural culture, or the expression of obscure private obsessions through the medium in which he was trained. Lequeu is compelling precisely because of these ambiguities and the way in which the clarity and professionalism of his drawing – and the near plausibility of his architecture – are constantly in danger of being fractured by his obsessiveness.

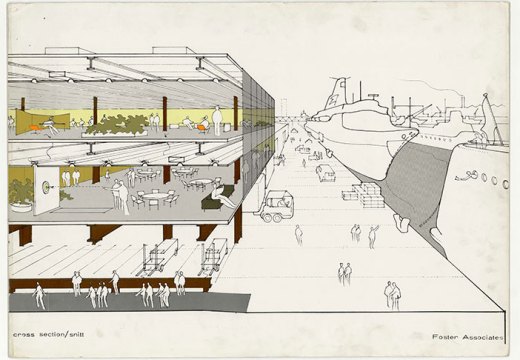

Machine for circulating water from the ditch to every floor of the castle (n.d.), Jean-Jacques Lequeu. Biblothèque nationale de France, Paris

The exhibition ends with Lequeu’s ‘lascivious drawings’, which were for a long time hidden away by prudish librarians at the Bibliothèque nationale. The curators attempt to downplay the pornographic intensity of these extraordinary images, praising their anatomical exactitude. His studies of genitalia are certainly scientific in their precise observation and in their interest in the effects of ageing and disease, but they are hardly detached. Similarly, his nudes are commended for abandoning a classicising aesthetic for a new naturalism. But the women in these works are essentially the same type depicted over and over; their most obvious distinguishing feature is what Lequeu described as ‘nourishing breasts’. Whether or not the intent was primarily pornographic, the effect is powerfully discomforting. There is much to be gained from the historical approach of this compelling and troubling exhibition, but Lequeu nevertheless remains a deeply peculiar artist richly suggestive for a psychoanalytical investigation.

‘Jean-Jacques Lequeu: Builder of Fantasy’ is at the Petit Palais, Paris until 17 March.

From the February 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home