In a speech entitled ‘Everything is Meaningless’ in the Book of Ecclesiastes, the nameless narrator ruminates on the vanity of material existence. ‘All things are wearisome’, he declares, ‘more than one can say’, and resolves that ‘the eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing’. Jennifer Packer has borrowed from Ecclesiastes 1:8 for the title of her exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery. This is far from being as dispiriting as you might imagine. As an early December downpour fell in Hyde Park, I walked into the South Gallery and was overwhelmed by the force of the paintings inside.

‘The Eye is Not Satisfied With Seeing’ is the Bronx-based artist’s first exhibition in a European institution. It features 35 works, from those made when Packer was an MFA student at Yale School of Art in 2011 to canvases completed only weeks ago. These enigmatic and absorbing paintings are an exercise in slow-looking – and evidence of what painting can offer at a time of crisis. Packer has said that her inclination to paint from life ‘is a completely political one’ and that her subjects ‘deserve to be heard and to be imaged with shameless generosity and accuracy’. The portraits, still lives, and interior scenes find beauty in the familiar – in brilliant floral socks (Tia, 2017), in the clutter of our bedrooms (Fire Next Time, 2017). More than anything else, though, Packer directs our gaze to the overlooked.

Say Her Name (2017), Jennifer Packer. Private collection. Photo: Matt Grubb; courtesy the artist, Corvi-Mora, London and Sikkema Jenkins & Co, New York

Say Her Name (2017), which refers to the social movement to raise awareness for Black female victims of police brutality in the United States, is an exquisite still life of a funerary bouquet that fills the canvas in a headlong flurry of Expressionist colour. It is one of several works that demonstrate how steeped Packer is in art history, recalling Henri Fantin-Latour and the Dutch 16th-century tradition of the vanitas that inspired him. ‘My favourite quality about [Fantin-Latour],’ says Packer, ‘is that he gives life and then threatens that life in the same picture.’ Dedicated to Sandra Bland, a 28-year-old Black American woman who died in police custody in Texas in 2015 – her death was ruled a suicide but many believed she was murdered – Say Her Name is a memento mori for someone Packer never knew, yet whose loss she grieved.

When conducting research for the painting, Packer tried to search for images of Bland’s memorial, but they couldn’t be found. In a recent interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, the artist said: ‘When you go to a funeral, the flowers aren’t a stand-in for the body. They’re a stand-in, in a way, for desire and for consideration. They’re a beautification, but we wouldn’t call them unnecessary attributes at a funeral. You wouldn’t call the lilies on a casket decadent, right? You’d just say, “This can’t even match what I’ve lost.”’

Blessed Are Those Who Mourn (Breonna! Breonna!) (2020), Private collection. Photo: George Darrell; courtesy the artist, Corvi-Mora, London and Sikkema Jenkins & Co, New York

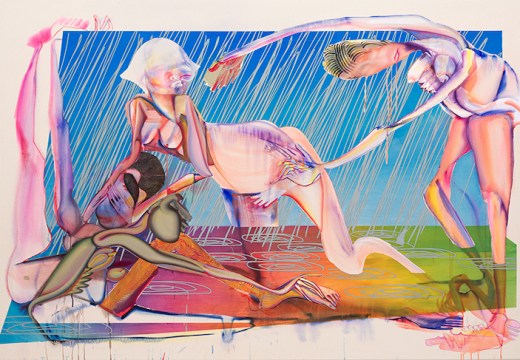

The titles of Packer’s paintings often lend tones of lamentation to scenes of everyday life. Blessed Are Those Who Mourn (Breonna! Breonna!) (2020), which was commissioned especially for the exhibition, is Packer’s largest painting to date at 3 x 4.38 metres. Its title refers to the killing by police of Breonna Taylor on 15 March 2020 in her own home in Louisville, Kentucky, and recalls the past year’s collective mobilisation against racial injustice in the United States. The painting depicts the interior of an apartment, a twenty-something-year-old man reclining on a sofa in the foreground. It is awash with oils in green, yellow, and pink. The objects are more than decorative filler: a whirring fan provides respite in the oppressive summer heat, a tiny print with Batman insignia implies that children reside in this home. For Packer, equal importance is given to ‘the adornment of the environment’ as to the sitter themselves: ‘there’s no hierarchy’. This compositional approach is once again political. This staggering, mural-like work is a response to the photographs of Taylor’s house after the shooting: the victim’s things – saucepans, photo albums, a night-stand – are interspersed with bullet rounds. Traces of a life remain. ‘I feel a lot of artists use figuration as a sort of stand-in for the everyman,’ Packer has said. These paintings could not be more specific, more attentive to the many facets of personhood.

Jordan (2014), Jennifer Packer. Private collection. Photo: Marcus Leith; coutesy Corvi-Mora, London

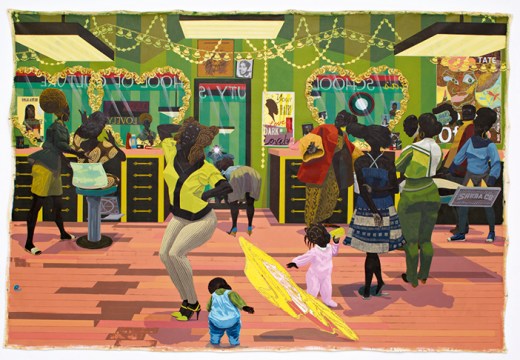

A number of the portraits on display are of Packer’s friends from the New York artistic scene, many of whom are making work that similarly addresses the politics of race and representation. There is a tender portrait of the artist Eric N. Mack, who sits on a wooden chair in a brilliant blue jacket, his eyes fixed on something out of view. Up until recently, Mack and Packer shared a studio; now, they both have their own spaces, still in the same building, in the Bronx. Jordan Casteel, whose own portrait of the designer and activist Aurora James for the cover of Vogue in September 2020 catapulted the painter to international recognition, has moved into the building, too. Jordan (2014) depicts its subject sitting for a portrait, the unfinished canvas in the background.

In April, Restless (2017), a portrait of the poet April Freely, a vase holding a spring-fresh bouquet floats just above the subject’s right shoulder, and in front of a mid-century typewriter with keys that resemble darting buds. Both of these objects, along with Freely’s figure, are submerged in translucent washes of a mustardy yellow. Packer does so much with single colours – often yellows, blues, and purples – that demonstrate the capacity of a restricted palette to convey the emotional state of a sitter. In this sense, Packer – like Casteel – is an inheritor of the Figurative Expressionist wing of the New York School, and the portraits move between painterly abstraction and fierce observation in a manner that calls to mind both Elaine de Kooning’s gesturalism and Alice Neel’s eye for personality.

April, Restless (2017), Jennifer Packer. Private collection. Photo: Marcus Leith

‘I wonder if I can make a painting that has impact,’ Packer has said. ‘Where the picture can make you turn away, but the painter’s touch could make you turn towards it.’ This push and pull is consistent throughout the exhibition, and if the eye is not satisfied with seeing alone in these pictures then it is because the works compel us to pay full attention to the worlds of politics and of friendship – even, or especially, when all things might feel wearisome.

The Serpentine, London, is temporarily closed to the public due to Covid-19 restrictions. For more information on ‘Jennifer Packer: The Eye Is Not Satisfied With Seeing’ (scheduled to run until 14 March) visit the institution’s website.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home