From the November 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Lace induced dangerous cravings among Renaissance-era consumers. Across Europe and into its colonial outposts, rulers tried to ban ever-frothier white filigree at the necklines, cuffs and hems of commoners. But threats of government fines, confiscation and scandal did little to deter fashionable men and women, as peddlers roamed the streets singing temptingly about lace ‘of the latest style’. Thanks to dozens of scholars who have collaborated on the Bard Graduate Center’s show, ‘Threads of Power: Lace from the Textilmuseum St. Gallen’, we even know how lace caused trouble in Florence in March 1638, when local authorities seized a particularly dandyish collar from a butcher named Nicolò.

The Bard Center display is the first major survey of the subject at a US institution since the 1980s. It dazzlingly conveys not only how wearers of lace climbed social ladders, but also how they financed the careers of the women who stitched it with bleary eyes. The seed for the current show was ‘Lace and Status: The Collection of Historical Lace in the Textilmuseum St. Gallen’, held at the Swiss institution in 2018–19. It focused on pre-1800 material and the Bard Center’s team, led by Emma Cormack, Michele Majer and Ilona Kos, have expanded the checklist with loans from private and institutional collections. Four floors of galleries explore traditions across continents, spanning the 16th to the 21st centuries.

The chronological arrangement examines lace incorporated into garments and furnishings for Habsburgs, mixed-race families in 18th-century Peru, French women at car races in the 1930s and Michelle Obama; the Bard Center has borrowed her golden wool filigree ensemble, designed by Isabel Toledo for the inauguration in 2009. Videos show disembodied hands demonstrating historic techniques with pins, needles and bobbins, and modern machinery emulating handwork. The contrast could not be greater between the clunky-looking tools and the ethereal results.

The labels and catalogue essays provide feasts of rarefied terminology; my favourites include Italy’s puncetto and reticella lace, with geometric forms, and France’s intricately floral blondes de fantaisie. The display cases allow visitors to lean in close to showstoppers such as a yellow taffeta ballgown striped with black Chantilly lace, worn in the 1850s by the author and artist Fanny Appleton Longfellow. Homage is paid to pioneering lace collectors of the 19th and 20th centuries who made shows like this possible. The holdings of the father-son collector team of Anthony and Arthur Blackborne, for instance, are partly preserved at the Bowes Museum in in northern England. The Blackbornes persuaded British aristocrats ‘under the seal of profound secrecy’ to part with lace ‘laid up in lavender for generations’, as Arthur wrote in a essay of 1909. (The exhibition, alas, leaves out Manhattan’s renowned mid 20th-century lacemaker, vendor, historian and restorer Marian Powys, who stitched airplane motifs on bridalwear and supplied antique treasures to institutions including the Metropolitan Museum of Art. That lapse is being remedied by a Powys biography in progress by design writer Julie Lasky.)

The curatorial team has delved into the lives of European lacemakers in pre-industrial times, who survived on pittances while ‘persistently stigmatised as simpleminded or immodest’, a label text notes. With children pulling at their skirts, they tried to preserve their eyesight, huddling close to windows and using glass spheres to amplify candlelight.

Evidence of women’s simmering rage and fantasies of revenge is scattered throughout the displays. A ground-floor case contains a crimson collar by the contemporary lace artist Elena Kanagy-Loux, a commission from the Bard Center that required hundreds of hours of manipulating pins and bobbins. It depicts scenes from the story of Judith beheading Holofernes. (Another major recent work by Kanagy-Loux in institutional hands is a collar for Ruth Bader Ginsburg, patterned with the number 25, commissioned in 2018 from Columbia Law School to honour the justice’s 25 years of Supreme Court service.) In a strip of 17th-century Italian linen lace, Holofernes’ severed head drips blood against backdrops of flowers – did any past owners brave legal proceedings to wrap that textile around their body parts? Captions for a touchscreen full of portrait photographs observe that elite Black women in 19th-century America often wore elaborate lace collars. They wanted their necklines to convey status and dignity, defying racist assumptions about their access to luxury goods, level of sophistication and moral fibre.

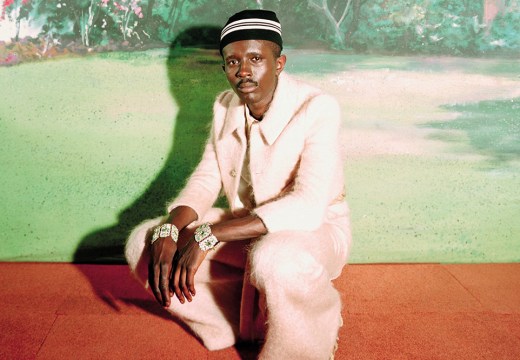

An upstairs gallery is dominated by recent products from St Gallen factories, which have supplied feather-laced sequinned lurex and silicone curlicues to couture houses. Visitors expecting a broader perspective on the contemporary scene may find this section a little too corporate, a problem compounded by the catalogue’s long Q&A with boosterish lace-industry executives. In a top-floor hallway, I longed for more space to step back and admire an electric-blue filigree outfit – Bard Graduate Center alumna mary adeogun inherited the machine-made garment from her Nigerian family and enhanced it with rhinestones.

During most of the exhibition’s run, the Bard Center is offering public demonstrations and classes with makers from the Brooklyn Lace Guild, which was co-founded by Kanagy-Loux. During my visit, I was encouraged to touch the antique and contemporary tools and samples around the classroom. I made crinkling sounds with a long band of experimental plastic filigree woven from recycled grocery bags; Kanagy-Loux told me about musical tones emanating when she clacks together bobbins made from various species of wood. I watched a group of women, experts and newbies side by side, creating gossamer hexagons of lace small enough to serve as dollhouse doilies. The stitchers shared tips as everyone methodically drew needles through little blue plastic sheets, which serve as temporary, disposable substrates for lacework threads. The instructor warned against needle moves that could cause chaos, and explained which sections would go unseen in the final product and could safely be left messy. I tried to follow along, but it all seemed like sheer alchemy.

‘Threads of Power: Lace from the Textilmuseum St. Gallen’ is at the Bard Graduate Center, New York, until 1 January 2023.

From the November 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home