This summer, the Centre of Ceramic Art in York (CoCA) at York Art Gallery is staging what, by the modest standards of the pottery world, amounts to something of a blockbuster exhibition: ‘Lucie Rie: Ceramics & Buttons’. As the UK’s best-known potter, Rie (1902–95) is currently the focus of keen public interest. One of her small yellow bowls from the 1980s recently broke records by selling at Sotheby’s for over £125,000 – a sum previously unheard of for British studio pottery.

Porcelain bowl (1955–60), Lucie Rie. Photo: Phil Sayer

Although Rie’s elegant modernist tableware and vessels are celebrated, her ceramic buttons, which she made while strapped for cash after arriving in London as an Austrian Jewish émigré in the 1940s, are far less famous. So little acknowledged is this part of her life’s work that Rie’s first biographer, Tony Birks, felt able to state: ‘Lucie made pots, and nothing else’. Offering a rounded overview of Rie’s output, the CoCA presents a truer picture of her life and work. It covers promising beginnings as a modernist potter in 1930s Vienna; hard times in wartime London; Rie’s struggle against the taste for the Anglo-Japanese pottery of the doctrinaire Bernard Leach and his followers; her growing success from the mid ’50s onwards; her championing of the German refugee Hans Coper, and her influence as a teacher. The buttons form a foundational part of this story. They are tactile, charming things – miniature wearable sculptures, as captivating as finely carved jewels.

During the Second World War, many British button factories were requisitioned for the war effort. At the same time, the government exempted buttons from rationing, believing such fripperies to be ‘socially necessary’ for the morale of women. Rie was employed by – and later herself employed – other Austrian Jews to fill this gap in the market, making handmade buttons for stores including Harrods and Liberty. At its height, the ‘Button Factory’, as her studio became known, employed 18 émigrés (including the then unknown Coper) and was producing 6,000 buttons per month. Colour-matching buttons to fabrics for designers – at the CoCA, the buttons are displayed on fabric swatches and patterns – laid the ground for her later mastery of glaze and clay chemistry.

Courtesy the Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts

The link between Rie’s work and fashion is long and rich. Her tiny frame was always clad in top-to-toe white (despite the clay); in 1989, the Japanese fashion designer Issey Miyake was inspired to make clothes for Rie. She responded by giving to Miyake a collection of ceramic buttons that had lain hidden away since the ’50s. These formed the basis for Miyake’s Autumn/Winter 1989 collection, which featured Rie’s buttons on oversized collars. Today, fashion designer Jonathan Anderson, a self-proclaimed ‘Rie obsessive’, collects her pots. Displayed near the buttons at the CoCA are sketch-like, unfinished dresses by designer Alison Walsh, inspired by Rie’s minimal fashion sense; their sole adornment a sculptural Rie button at the throat.

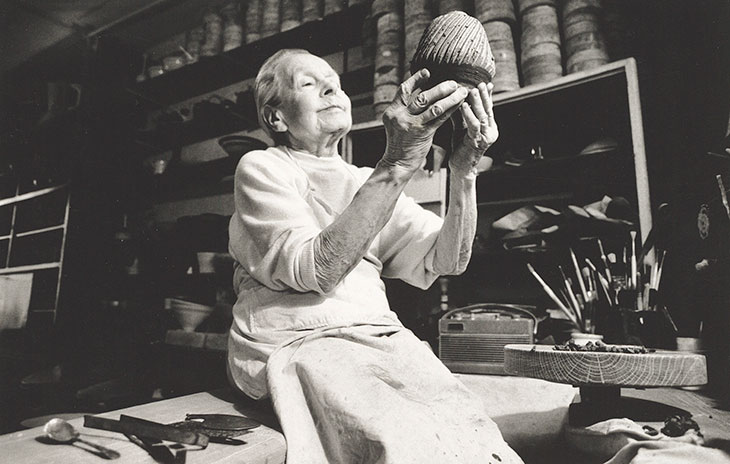

Elsewhere, we see the full range of familiar forms: carefully balanced tableware, slender-necked vases with flared rims, and conical bowls. Also featured is David Attenborough’s interview with Rie for BBC Omnibus in 1982, in which the veteran broadcaster appears as wide-eyed as a child, breathing ‘I barely dare speak’ as he watches her making on her potter’s wheel, decorating pieces and unloading a packed kiln. The latter activity gave rise to the unforgettable moment when the octogenarian potter, on her stomach as she attempted to reach a piece, asked Attenborough: ‘Could you hold my feet, please? I’m stuck’. After her death in 1995, Attenborough wrote in Ceramic Review that ‘[d]ignity could hardly have survived such an episode’. Nevertheless, the overriding impression of Rie given by the show is that of a dignified doyenne, determined in the face of life’s vagaries.

A group of eight twisted rope shaped buttons, some stoneware, some earthenware (1945–49), Lucie Rie. Photo: Phil Sayer

Why are these buttons – a moneymaking exercise, made largely on commission, and associated with the often-overlooked world of haberdashery – worthy of attention? Part of their interest derives from the vital stories they tell of survival and collaboration in a time of conflict. And without the urbane influence of the continental potters Rie and Coper, Britain would have spent longer stuck in a stylistic rut. But the buttons are also quite simply lovely objects. Why should a button be any less worthy than a teacup?

‘Lucie Rie: Ceramics & Buttons’ is at the Centre of Ceramic Art, York Art Gallery, until 12 May 2019.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home