Were he still alive, the late I.M. Pei may have had to hide behind the sofa during the first episode of Lupin, which sees a sports car crash through Pei’s iconic glass pyramid above the entrance hall of the Louvre. The treasure at the heart of this French heist series – currently beating even Bridgerton in the Netflix charts – is the Queen’s Necklace, which once belonged to Marie Antoinette. Its theft from the museum has been masterminded by Assane Diop (Omar Sy), a French-Senegalese con artist who models himself on Arsène Lupin, the gentleman thief created by the writer Maurice Leblanc in 1905.

Omar Sy as Assane Diop in ‘Lupin’. Photo: Netflix

There are parallels in tone here with the BBC’s Sherlock, and in fact Leblanc had his hero meet the aging British detective in a story published in June 1906, which he cheekily named ‘Sherlock Holmes Arrives Too Late’ (Leblanc was later obliged to change the name of the detective to ‘Herlock Sholmes’ after Arthur Conan Doyle objected). Beneath its thrills and humour, however, Lupin has plenty to say about class, racism and systemic corruption. Restitution, too. There’s a particularly wry scene in the fifth and final episode of this series, in which Diop, posing as a policeman, persuades a wealthy elderly woman to hand over her diamonds for safe-keeping. When she explains that her hoard came from her husband’s involvement in diamond mining in the Belgian Congo, Diop replies with a smile: ‘The good old days’.

It’s in gaining temporary employment as a cleaner at the Louvre that Diop has been able to work out the details of his heist. Mop in hand, he moves around the main galleries, passing Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, ignoring – vast canvas though it is – Veronese’s Wedding Feast at Cana, to gaze at the painting opposite, behind its bullet-proof glass: the Mona Lisa, bien sûr. Diop returns her smile, surely enjoying the fact that no paying visitor to the Louvre would have such privileged access to the world’s most visited artwork.

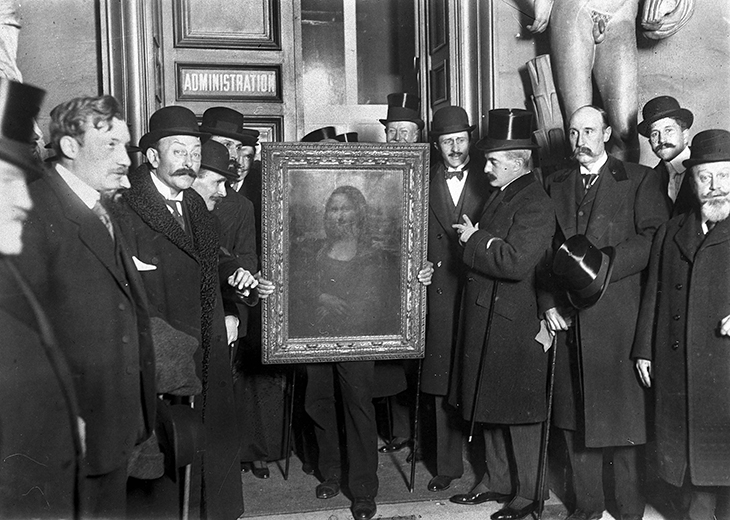

But perhaps Lupin’s creators also had in mind here the real-life theft of Leonardo’s painting in 1911 by a Louvre employee named Vincenzo Peruggia. Having hidden in a cupboard overnight, Peruggia took the canvas out of its frame and simply walked out of the museum the next morning with the Mona Lisa hidden in his coat. Some 24 hours passed before the painting was missed – and arguably it was the scandal of this theft, and the reproduction of the painting in print across the international press, that made La Gioconda as famous as she is today. (More people came to see the ghostly shape of the missing canvas on the wall than had ever come to see the painting itself.)

The Mona Lisa at the Louvre in January 1914, recovered after its theft in 1911. Photo: Roger-Viollet/Getty Images

Guesses at who was behind the theft ranged from J.P. Morgan to Kaiser Wilhelm, and the police questioned both Guillaume Apollinaire and Picasso as suspects. Peruggia was only caught when, 28 months later, he tried to sell the Mona Lisa to an art dealer in Florence – it had been stolen from Italy by Napoleon, Peruggia mistakenly believed, and belonged in the country of Leonardo’s birth. This daring thief could well have been inspired by recently published Arsène Lupin stories; but he clearly lacked the savoir-faire needed to escape ultimate detection. The rakish Assane Diop, on the other hand – well let’s just say your correspondent fancies his chances.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home