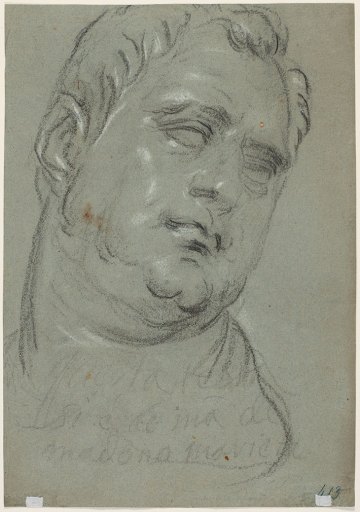

A black-and-white chalk drawing of the head of a portly man was recently sold at a Christie’s auction as the only work firmly attributed to Marietta Robusti, daughter of the Venetian master Jacopo Robusti, perhaps better known as Tintoretto. Reports from her contemporary biographers suggest that Marietta, who worked in her father’s workshop in the late 16th century, was an accomplished and sought-after artist in her own right. But in the centuries that followed she fell into obscurity. Now, amid a growing movement to reclaim the women artists so often neglected by history, Marietta has the potential to join 16th-century peers such as Lavinia Fontana and Sofonisba Anguissola in the history books – if only researchers could find some more of her work.

Head of a man, after the antique (verso) (16th century), Marietta Robusti. Photo: © Christie’s Images Ltd 2021

‘Marietta had a brilliant mind like her father. She painted such works that men were astonished by her talent,’ writes Carlo Ridolfi, author of a biography of Jacopo Tintoretto and two of his children, Domenico and Marietta, first published in 1642. Nicknamed ‘La Tintoretta’, Marietta – who, according to Ridolfi, dressed as a boy in order to assist her father on his projects – is recorded as having painted many portraits and produced works of her own invenzione. Another of Tintoretto’s early biographers, Raffaello Borghini, reports how Marietta was requested as a court artist by the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II, Archduke Ferdinand of Austria, and King Philip II of Spain – although ‘Greatly loving his daughter, [Tintoretto] did not want her taken from his sight,’ writes Borghini.

With such glowing accounts of Marietta’s artistic prowess, attempts to rediscover her work have been numerous and in some cases quite inventive. Unfortunately, these endeavours have rarely been successful.

One of the most commonly attributed paintings is a Self-Portrait with Madrigal located in the Uffizi’s Corridoio Vasariano in Florence. The painting shows a young woman in a white dress with her right arm resting on a harpsichord behind her and a music score in the other hand. The Uffizi labels the work as by Marietta Robusti in its online catalogue. However, art historians have questioned the credibility of this attribution based on provenance records, which show that the portrait was attributed to Titian by a Venetian collector in the 17th century.

Self-Portrait with Madrigal (c. 1578), attributed to Marietta Robusti. Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence

Most damning of all, though, is the mediocrity of the painting. The art historian Joanna Woods-Marsden comments in her book Renaissance Self-Portraiture (1998) that the rudimentary foreshortening and poor anatomy are hard to reconcile with the praise lauded on Marietta by her biographers. Duncan Bull, writing in the Burlington Magazine in 2009, dismisses it as ‘a feeble work that speaks more of Verona than of Venice, let alone of Tintoretto’s workshop’. The lack of naturalism and the stiffness of the sitter are worlds away from the fluid, energetic style characteristic of a pupil of the Venetian master.

‘Marietta’s special gift,’ according to Ridolfi, ‘was knowing how to paint portraits well.’ This was not unusual praise for 16th-century women artists, who were highly valued as portraitists. Women were considered to have an eye for detail, particularly jewellery and decoration on clothing, which was so crucial in portraiture for demonstrating a sitter’s wealth and status.

Several portraits have been tentatively attributed to Marietta Robusti. These include a Portrait of an Old Man and a Boy in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and the Rijksmuseum’s Portrait of Ottavio Strada. The attribution of the former painting rested on the signature ‘M R’ on the bottom left of the canvas; after cleaning, it appears that the signature actually reads ‘M 3’. The painting in Amsterdam, currently catalogued as by Jacopo Tintoretto, has received attention because Marietta’s early biographers mention a portrait she painted of the courtier Jacopo Strada. Some art historians argue that the biographers mistakenly cited Jacopo instead of his son Ottavio Strada – and that the Rijksmuseum’s painting is the portrait in question. But this is just one theory.

Portrait of Ottavio Strada (1567), attributed to Jacopo Tintoretto. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Plenty of historic catalogue entries attribute other work to Marietta, but evidence of these paintings is now thin on the ground. It is likely that Marietta also helped her father with public commissions, such as paintings in their local church in Venice, the Madonna dell’Orto. But her contributions in this respect are hard to pinpoint.

Just one drawing, therefore, is categorically attributed to Marietta. Head of man, after the antique, which sold at Christie’s in Paris last month for €100,000, depicts the Roman emperor Vitellius drawn from an ancient bust – a copy of which Tintoretto kept in his workshop. Scrawled across the drawing are the words ‘this head is by the hand of madonna Marietta’, probably added by her father to distinguish the drawing from the countless others that would have lain about the workshop.

This drawing is a much-needed example of Marietta’s talents. As Stijn Alsteens, international head of Christie’s Old Master drawings department explains to me via email, ‘Marietta in her time was admired as a portraitist, and the drawing can be said to reflect her interest in physiognomy.’ The drawing, Alsteens says, confirms Ridolfi’s account that Marietta was a gifted member of her father’s studio, on an equal footing with her male counterparts.

In the drawing, Marietta captures the head in soft, swift strokes, economic shading and dashes of highlights. We see the fluidity and movement expected of an artist trained by Tintoretto. On the recto of the sheet is another drawing from Tintoretto’s workshop of unknown attribution portraying the face of Giuliano de’ Medici. ‘Where the recto is mostly a study of light and shadow, the verso focuses on the distinctive features of Vitellius’s face – true to Marietta’s gifts as a portraitist,’ Hélène Rihal, head of Christie’s Old Master drawings department in Paris, said in advance of the sale.

Although the attribution is accepted, it is only one drawing and that poses a dilemma for anyone seeking to restore Marietta’s reputation. The historical evidence has the potential to put Marietta on a par with contemporaries like Fontana or Anguissola. The gaping hole is the physical evidence. For the moment La Tintoretta, the legendary woman artist, remains just that – a legend.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home