In 1720 England was on the verge of a smallpox epidemic. Lethal to children, throughout the 18th century in Europe the disease caused 400,000 deaths each year; it was only eradicated in 1979. In Constantinople, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, wife of the British ambassador, had observed that smallpox was rendered ‘harmless by the invention of engrafting’ and in April 1717 wrote: ‘I intend to try it on my dear little son. I am patriot enough to take pains to bring this useful invention to fashion in England.’ The boy was successfully inoculated in 1718 by the embassy surgeon, Dr Maitland, as was his younger sister in 1721 on their return to London, both with complete success.

Lady Mary’s example heralded the first wave of inoculation in England. The leading London physicians Hans Sloane and Richard Mead conducted trials in Newgate Prison in 1721. Claude Amyand – trained in France and naturalised in London in 1698, and Royal Surgeon from 1715 – successfully inoculated George I’s grandchildren in 1722 and then served George II’s family.

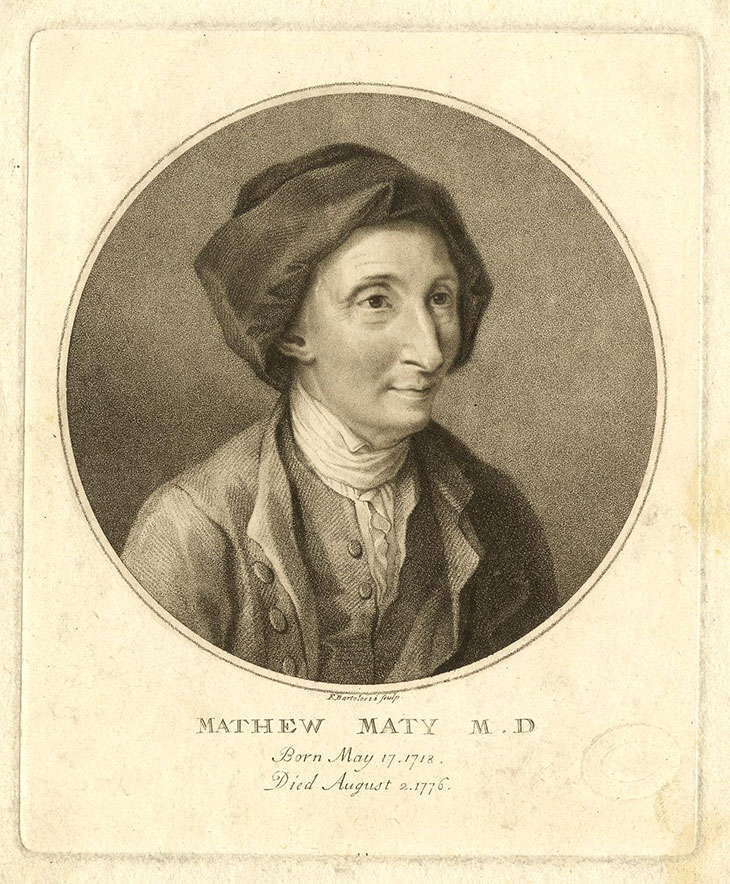

A resurgence of the epidemic in 1738 in Africa stimulated a wave of 2,000 inoculations in Middlesex. Dr Mead promoted this preventive treatment at the newly established Foundling Hospital and a campaign was taken up by the young Huguenot doctor Matthew Maty (1718–1776) in London from 1740. Like Mead, Maty had studied medicine in Leiden. Maty also developed a reputation as a journalist – in 1750 he founded the Journal Britannique which publicised British books abroad and in 1752 reported on the benefits of smallpox inoculation in Boston, Massachusetts, where, of almost 2,000 inoculated, only 24 had died. A portrait of Maty aged 36 by the Swiss artist Barthelemy Dupan was later bequeathed by the doctor to the British Museum.

Dr Matthew Maty (1754), Barthelemy Dupan. Photo: © Trustees of the British Museum

Richard Mead and Hans Sloane were also celebrated collectors. As one of the British Museum’s first three under-librarians from 1756, Maty received Sloane’s natural history collections as well as the Royal Library given by George II in 1757. Meanwhile Maty gained international recognition in Berlin, Haarlem and Stockholm. From 1762 he was secretary to the London-based Royal Society.

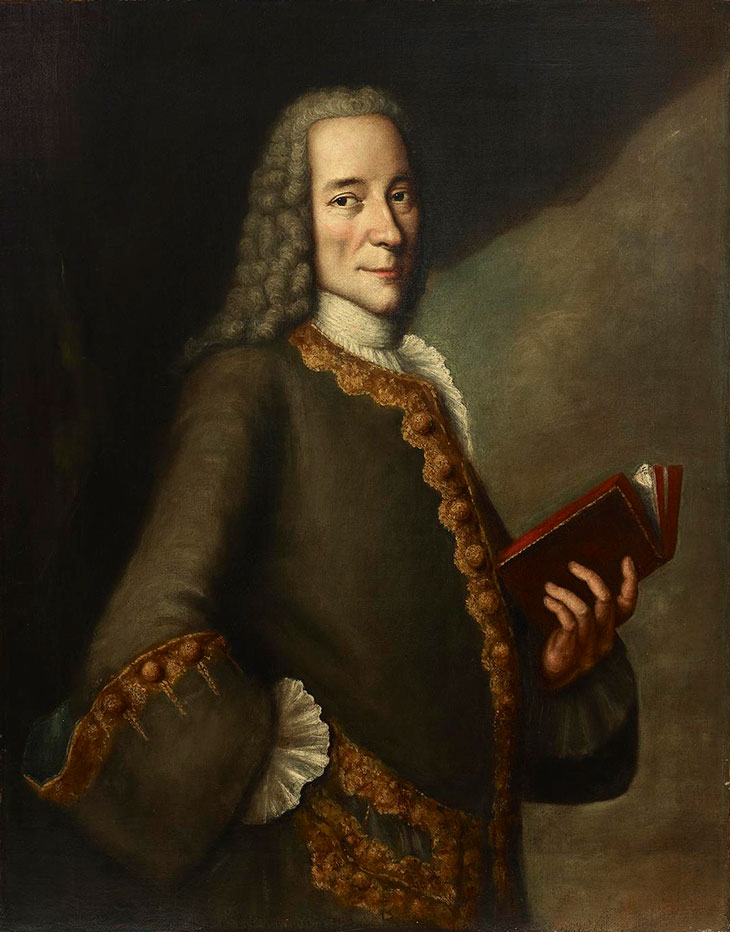

On 31 October 1760 Maty gave the British Museum a portrait of Voltaire by ‘a young painter of Geneva Mr Gardel [sic]’. According to the Life, Trial and Last Words of Théodore Gardelle, published in 1761 and preserved in the Law Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., Gardelle was born and apprenticed in Geneva, where he did his portrait of Voltaire and enamelled it for a snuff box. Thanks to Voltaire’s introduction, Gardelle studied painting in Paris and later worked in Brussels and The Hague before coming to London as a miniature painter in 1759. The painting in the British Museum is Gardelle’s only documented portrait.

Voltaire (c. 1755), Théodore Gardelle. Photo: © Trustees of the British Museum

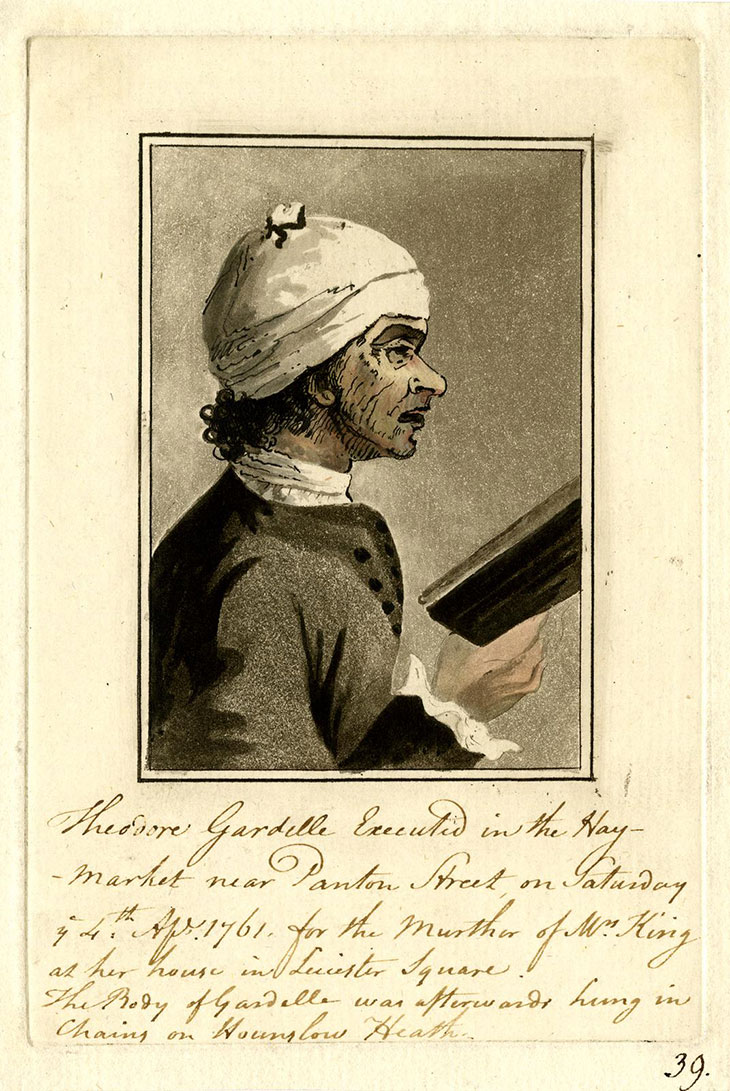

In February 1761 Gardelle murdered Anne King, the landlady at his lodgings in Leicester Fields (now Leicester Square). He was committed to Newgate Prison and tried at the Old Bailey where he ‘professed himself a Protestant’. Gardelle was executed on 4 April 1761. The account of the murder published in the Gentleman’s Magazine reads like a ‘Modern Moral Subject’ by William Hogarth, who contributed to this likeness of Gardelle captured on the cart riding to his execution.

Théodore Gardelle (1794), Samuel Ireland after John Inigo Richards and William Hogarth. Photo: © Trustees of the British Museum

On the day of the murder, Gardelle sent the housemaid to collect snuff from Haymarket. Anne King had previously sat for a portrait by him, and – according to his testimony – it was her ‘satirical and provoking’ critique of the result that led to the physical assault. He pushed his victim, who fell against her bed post. To silence her screams Gardelle used her ivory comb (it had a tapered point) as the murder weapon. He concealed the body and continued with his daily life although appearing dejected to his friends who arranged for ‘a woman of the town’ to entertain him. It was she who uncovered the crime.

Maty visited Voltaire at Ferney in 1750 and probably acquired the portrait from Gardelle in London. Displayed at the British Museum’s first home at Montagu House in 1761, it apparently failed to attract publicity despite Gardelle’s notorious crime and execution. The portraits of Voltaire and Maty were both displayed from 1842 in Robert Smirke’s newly completed building.

Matthew Maty (1777), Francesco Bartolozzi. Photo: © Trustees of the British Museum

Among his many other interests, Maty also promoted sculpture by Louis-François Roubiliac. His poem on Roubiliac’s statue of Handel in Vauxhall Gardens appeared in the Mercure de France in 1750. In 1762 Maty gave the museum 17 portrait busts acquired at the sculptor’s posthumous sale and in his 1776 bequest were busts of Petrarch, Boccaccio, Machiavelli and Dante, not traced today. He instructed his wife Mary to employ Bartolozzi, or another eminent engraver, to make 100 prints ‘from the best drawing or picture done for me’ as a memorial gift for his wide circle of friends. In 1799, a copy of Bartolozzi’s portrait of Maty was among the portfolios bequeathed to the British Museum by Clayton Mordaunt Cracherode.

As a 2019 Getty Rothschild Fellow, Tessa Murdoch wrote on Huguenot refugee art and culture (publication forthcoming in 2021).

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home