In Apollo’s current March issue we spoke to artist Michael Craig-Martin ahead of his exhibition at Chatsworth House, which opened last Sunday.

The exhibition at Chatsworth looks to have given you a lot of freedom with the house and its collections. How did the project come about?

I met the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire because I was asked by Lady Burlington to do a portrait of her for Chatsworth. There’s an extraordinary tradition of making portraits of the future Duchess, which reaches back to Gainsborough and Reynolds through to Sargent and Freud – and I got to be the next on this list of people, amazingly enough. We spoke a great deal, and then the Duke asked me if I’d be interested in exhibiting sculpture there – and the other aspects flowed from that. The most daunting thing has been doing something that’s a kind of intervention in the house. On one of my visits, the Duke said that he and his wife were worried that I was feeling intimidated by the house – which of course was exactly true – and that he wanted me to put that aside, and tell him there and then what I’d propose to do if I wasn’t so anxious about interfering.

Some of the sculptures you’re showing have been seen before, but others are exhibited for the first time. Have they been specifically created for Chatsworth?

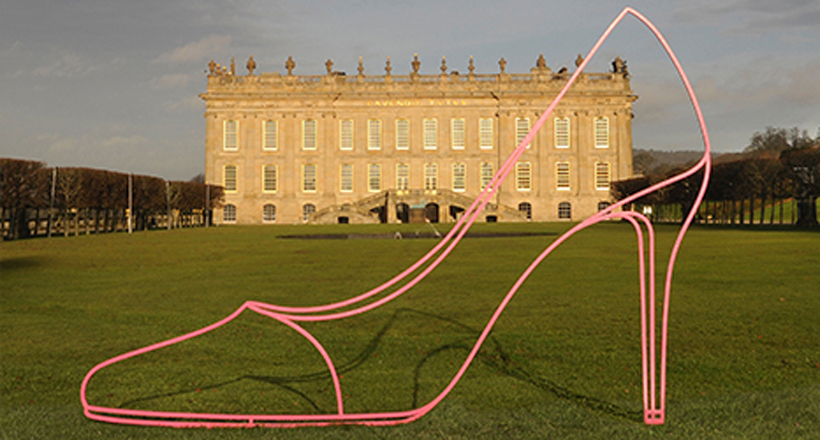

Because I make single images that have a very particular association, when it came to making outdoor sculptures to go in gardens, it was natural for me to think in terms of garden forks, wheelbarrows, pitchforks – things to do with the land and landscape tools. The only image that’s really very different is the pink high-heeled shoe – there’s something about the shoe in relation to the house. The house is an extravagance – and it seems to me that women’s high-heeled shoes are the most extravagant of all simple objects.

Setting contemporary sculpture in historic landscapes is very much in vogue. What types of challenge do such surroundings pose for the artist and curator?

The fact is that you discover, when you make sculptures to go outdoors, that there aren’t a great many opportunities for these things to be seen in a public way. It strikes me as amazing that Gagosian, with all its many galleries, doesn’t have one that is an outdoor space where sculpture can be seen.

Some of these sculpted objects take up motifs from your graphic works. How are they transformed by this medium and scale?

The most important thing to say about my sculptures is that they’re non-sculpture – they’re not sculptures of objects, but of drawings of objects. They’re flat: I could make something that’s four metres high and two metres across, but from the side it’s only a few centimetres thick. The illusionism is two-dimensional. One of the breakthroughs for me was the realisation that it was possible to make these works so that they could be supported under the ground. They appear to sit just on the grass. They’re made of steel of course, and are actually very heavy, but look almost weightless.

There are several aspects to your curatorial involvement in this project. What guided your selection of works for the sculpture trail in the house?

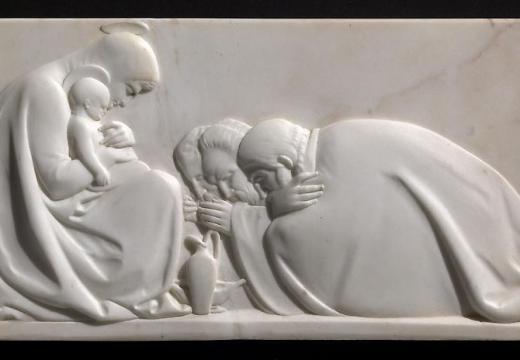

When you go somewhere like Chatsworth, which is overwhelmingly voluptuous – the house, its contents, it’s unbelievable what’s there – the effect is often that of the overall room or house. What I’ve tried to do is to find something that features throughout but would let me draw attention to specific things – and I settled on full-figure sculptures. Because so many are from the 17th – particularly the 17th – and 18th centuries, they have very grand and elaborate plinths. I’ve had all of the marble, carved and mosaic plinths covered in magenta material. I’m trying to draw attention to the sculptures, which become detached from their surroundings in a particular way. The effect is very beautiful with the Canovas in the Sculpture Gallery – they seem to be floating in space.

How did you select the Old Master drawings that are on show in the Old Master Drawings Cabinet?

The room isn’t very big and can only take a hanging of about 15 drawings – no more than 20. I wanted to find a group of works that would sit together. Going through the catalogues, I realised that the drawings that struck me most strongly were portrait heads where the head almost fills the page. Most of these drawings are not terribly big and so if the scale of the image is as big as the paper, those are in a sense the biggest drawings in the collection. I asked to see every one of them, and the curator pulled out the actual drawings and we both were astonished when we saw what was there, when you isolated them in this way. They cover three centuries and they’re from infancy to old age; people who are beautiful and people who are ugly; idealised faces and natural faces. It’s a very extraordinary set of drawings.

And is this again part of that impetus to look at things afresh?

Exactly. I always think that when artists look at things, they don’t look at things in the same way that historians do. This is a completely, ahistorical selection. It’s trying to focus on the single thing and then see what happens in the grouping that results ‘Michael Craig-Martin at Chatsworth’

‘Michael Craig-Martin at Chatsworth‘ runs until 29 June 2014.

Click here to buy Apollo’s current March issue

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home