A round-up of the week’s reviews and interviews

Travelling Treasures: The Frick Collection at the Mauritshuis (Emma Crichton-Miller)

For the first major art exhibition in its much-admired new space, the Mauritshuis has secured the loan of 36 exceptional works of art from the New York institution. This is the first time the Frick has lent a substantial group of works for a travelling exhibition. It is gesture not just of immediate gratitude but of mutual recognition that the two institutions – with their small but outstanding collections, largely reflecting the taste of single individuals or families, in landmark buildings created as private homes – share characteristics.

Installation view: ‘Agostino Bonalumi – Sculptures’, Mazzoleni London. Courtesy Archivio Bonalumi and Mazzoleni London

Agostino Bonalumi at Mazzoleni Art, London (Rosalind McKever)

Bonalumi matched forms, materials and colours, and while he has an immediately recognisable style, his work is not repetitive. However, in the last decade of his life he cast in bronze forms previously made in less-reflective materials, to discover how a polished finish would change them. In his paintings too, light is all-important. In Rosso (1973) geometric ‘extroflexions’ distort the canvas at different angles to create shadows; the form created and the form implied by the shadows are contradictory.

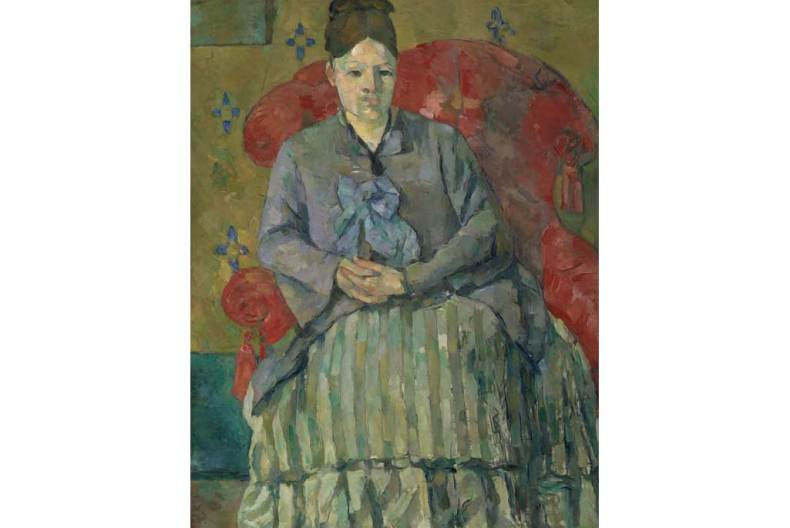

The Lady Vanishes: ‘Madame Cézanne’ at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Raisa Rexer)

She is the constant subject who sets in relief the endless variability in Cézanne’s approach, his experimentation with form and colour. Ever-present but impossibly mutable, Hortense the woman necessarily vanishes under the accumulated weight of her many portraits, leaving behind only Hortense the model, the mere physical matter whose form is endlessly transfigured by the painter’s perception and brush.

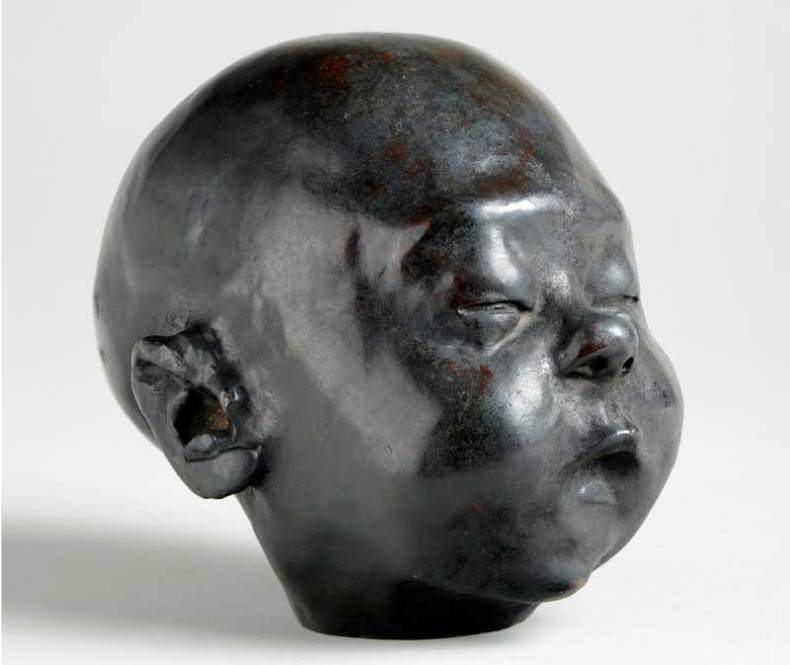

Baby Asleep (1904), Jacob Epstein © The estate of Sir Jacob Epstein. Photograph: Leeds Museums and Art Galleries, City Museum

Family Man: the Foundling Museum presents another side to Jacob Epstein (Danielle Thom)

The personal narrative is presented candidly and with neither sordidness nor sentiment – Epstein’s flaws are on show, as well as his fatherly impulses. But, on a site with such a long and sad history of child abandonment and parental anguish, it is touching to witness the parental love and pride manifested in the precise, expressive busts and sketches of the Epstein children and, later, grandchildren.

Revolutionary whimsy: ‘Ruth Ewan: Back to the Fields’ at Camden Arts Centre (Fatema Ahmed)

The very first item in Ruth Ewan’s exhibition at the Camden Arts Centre was missing when I visited on the Sunday after it opened. In Back to the Fields, Ewan has represented the French Republican calendar by placing the object each day is named after in the main gallery. When I asked the attendant where the grape for the first day of Vendémiaire was, she explained that the fresh items in the display need to be replaced regularly and that no one had had a chance to go to the shops yet.

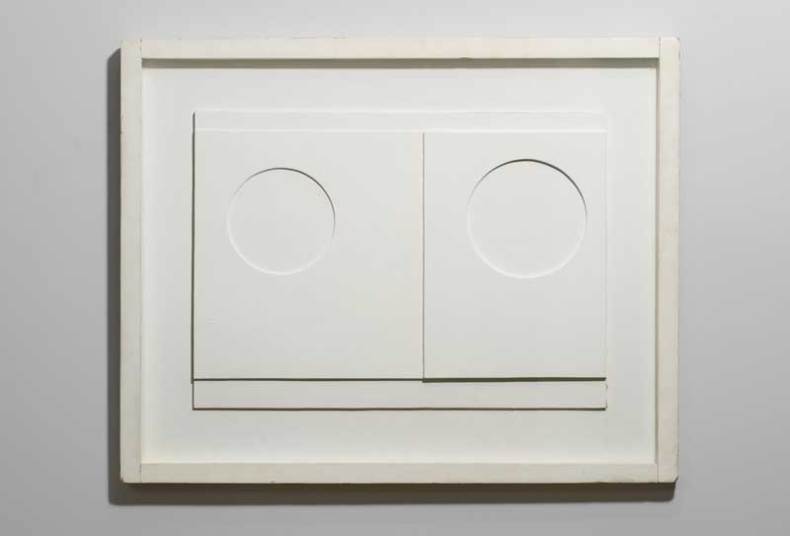

Pure abstraction: ‘Sotto Voce’ and the appeal of the abstract white relief (Wessie du Toit)

‘Abstract white relief’ is not an easy term to get your head around. It can sound highly technical, or positively poetic: three slight and airy words that threaten to float away like a balloon as soon as they are said. Yet this simple sensation of transcendence was precisely the intention of many of the artists who used abstraction and whiteness to transform the ancient medium of relief sculpture during the 20th century. They sought to turn an object in the physical world into a window through it.

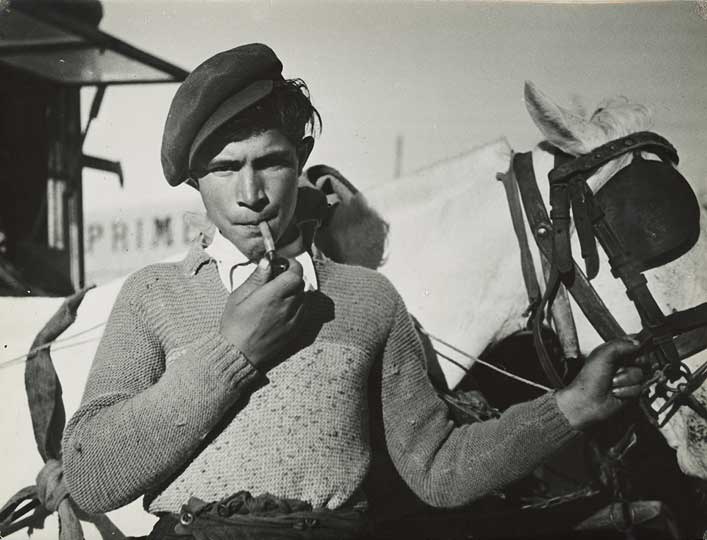

‘Lore Krüger: A Suitcase Full of Pictures’ at C/O Berlin (Peter Yeung)

Three years ago, a mysterious middle-aged man contacted the curator of Berlin’s C/O Gallery, Felix Hoffmann, out of the blue and handed over a battered old suitcase crammed with enchanting vintage silver gelatin photographs. That person was Peter Krüger, son of Lore Krüger – a woman who was erstwhile unknown to the photography world, yet one whose work would prove to be a discovery almost in parallel with new-found luminary Vivian Maier and her startling 1950s New York City street photography.

Fig-2 at the ICA: a rehashed pop-up exhibition that somehow works (Digby Warde-Aldam)

Make no mistake – the first four shows have not been blockbusters. Sensationalism this ain’t. You might even go as far as saying they’ve been counter-intuitively modest. On the whole, though, what we’ve had so far has been pretty impressive.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home