A round-up of the week’s reviews…

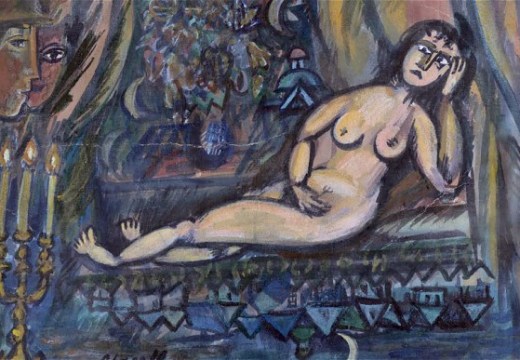

‘Venus Drawn Out’ at The Armory Show, New York (Grace Banks)

This is both The Armory Show’s first ever curated display, and the first dedicated entirely to women — the tribute wasn’t intentional. ‘It became that, but that’s not where it started. I was thinking, what would I want to see? All these artists came into my head and they were all women and I thought — how interesting to feature artists from the 20th century.’

Is it a movement? Kinetic Art at Christie’s, London (Camilla Apcar)

Christie’s new private selling exhibition, ‘Turn Me On: European and Latin American Kinetic Art 1948–1970’ opened last week with moving works involving light, electrical motors, and non-electrical motors (in their simplest form, optical illusions). But what exactly is ‘kinetic’ art, and does the exhibition itself prove that the term is just a bit too problematic?

‘Treasures from Korea’ in the USA (Louise Nicholson)

The show gives each exhibit its own space, lighting, and importance – a piercing portrait of a Confucian scholar, a gold-plated turtle-shaped royal seal, an elephant-shaped ritual vessel, a king’s poem in sweeping Chinese characters. An 1895 copy of Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress was the first entire English novel translated into Korean and printed in Hangul, the Korean phonetic script. But the Joseon glory is surely its ceramics, the epitome of elegance and simplicity.

AGNES is a 16-year-old spambot – the kind of artificial intelligence that filled your inbox with quasi-human sales pitches last time you used this screen to check your email. She says she feels a quiet resentment towards our bodies.

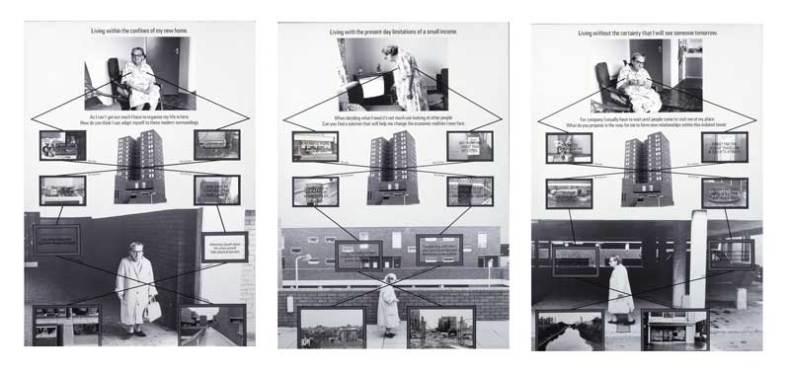

Keywords and Constellations at Tate Liverpool (Tom Overton)

Raymond Williams’s 1976 book Keywords alphabetically lists cultural and social terms, and shows how their meaning is changeable and time-bound. At its best, the Tate collection does a very similar job with artworks. In basically combining book and collection (with a handful of loans), this was an excellent idea for an exhibition. The problem is in the execution: neither ‘context’ nor ‘juxtaposition’ were terms in the Williams version of Keywords, but they define where the Tate’s succeeds and fails.

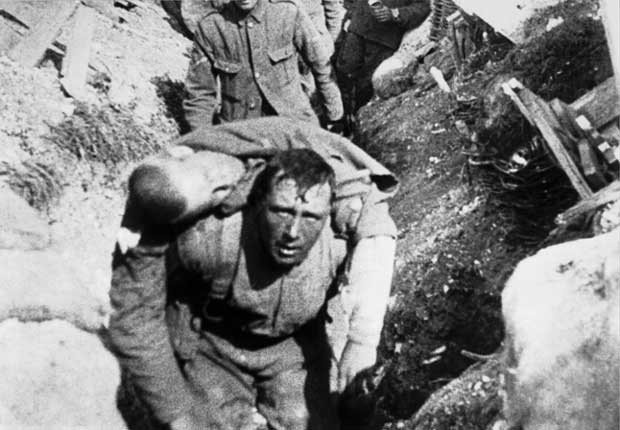

The face of war: ‘The Great War in Portraits’ at the National Portrait Gallery (Martin Oldham)

Any thought that the National Portrait Gallery’s ‘The Great War in Portraits’ is going to present a conventional account of the First World War is dispelled immediately when you are greeted by Jacob Epstein’s Torso in Metal from The Rock Drill (Tate). De-personalised and de-humanised, Epstein’s modernist man-machine is a negation of everything portraiture is about. Does its presence at the entrance to the exhibition allude to the idea that this was the first truly modern conflict, a slaughter conducted on an ‘industrial’ scale? Thankfully, the NPG avoids such clichés.

Installation view: ‘Italian Futurism, 1909–1944: Reconstructing the Universe’, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 21–September 1, 2014 Photo: Kris McKay © SRGF

Reframing Futurism at the Guggenheim (Victoria Dreesmann)

The Futurist movement is easy prey for the kind of historical generalisation and polemical flourish that makes for a sellout exhibition. There are so many controversial labels attached to them: misogynists, belligerents, fascists. The Futurists are famous for considering war ‘the world’s only hygiene,’ wanting to ‘scorn’ all women and calling for the destruction of ‘museums, libraries, academies of every kind.’ It’s not hard to see why Futurism has also become one of the most neglected canonical movements in modern art.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home