Korea, an enigmatic land for the majority of westerners, is introducing its art, history and philosophies to the US. A rigorously selected show of top quality art made during the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910) – most pieces leaving Korea for the first time – has begun its year-long tour at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (March 2–26 May). It will continue to Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts, swapping a good number of fragile paper items at each location.

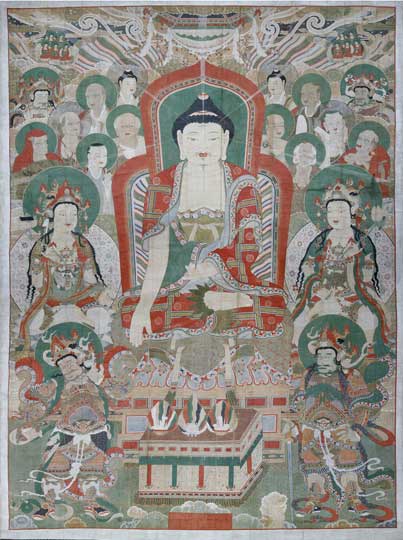

The opening event at Philadelphia was a lavish affair. The setting was the museum’s grand staircase, at the top of which hang Rubens’ masterful History of Constantine tapestries. But they were overshadowed by a vast backdrop covering the wall: a 39ft-high Buddhist ‘gwaebul’ (banner painting) made in 1653 and depicting Sakyamuni (Historical Buddha) reciting the Lotus Sutra to bodhisattvas, disciples and heavenly kings. For more than 350 years it has been the central object of worship during the celebrations of the Buddha’s birthday and for the Yeongsanjae ritual, when prayers are offered for the deceased on the 49th day after their death to encourage the seventh King of Hell to pronounce a favourable judgement – ideally a release from re-birth.

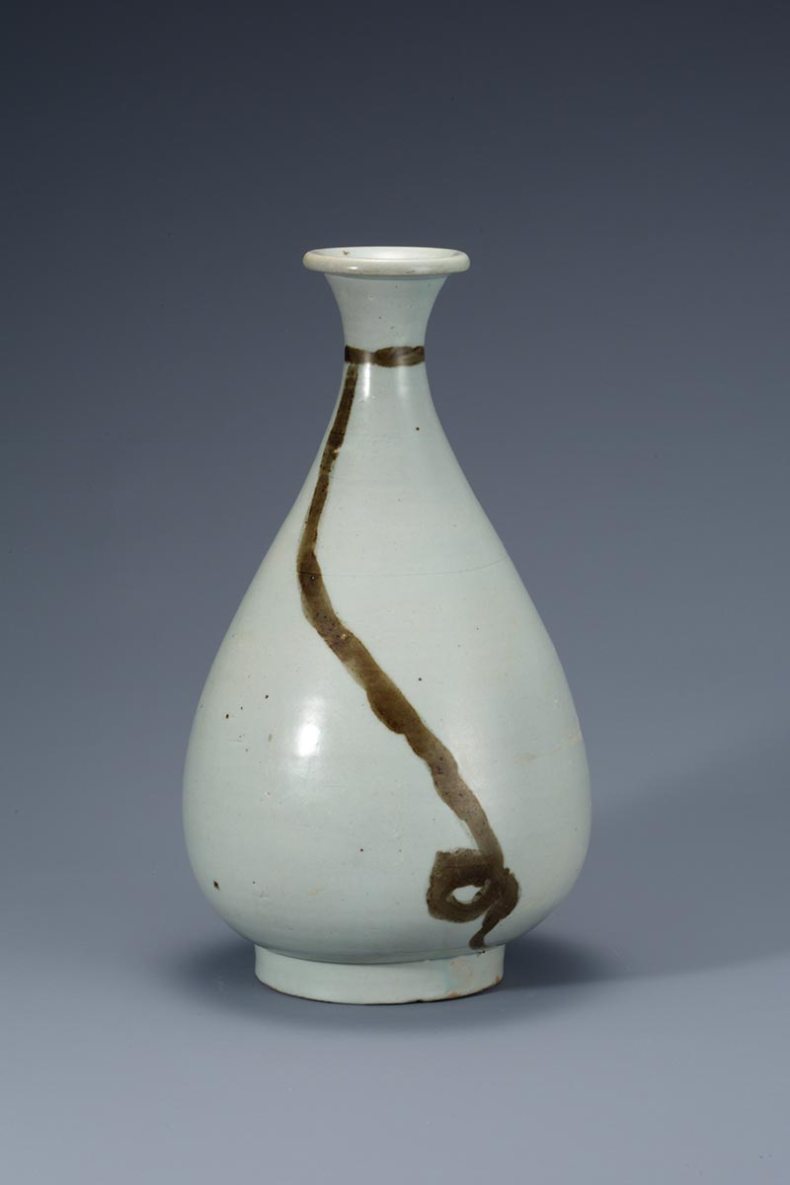

Bottle with Decoration of Rope, Artist/maker unknown, Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), 16th century. National Museum of Korea, Seoul

Louise Nicholson explores Korean art from the Joseon Dynasty in the March issue of Apollo

With the museum transformed into this sacred space, seven monks performed the rhythmic Yeongsanjae ritual, the crowd below mesmerised by dramatic drum beating, trumpeting, solemn multi-part chanting, cymbal-clashing and swirling meditative dancing. The spectacle set the tone for exploring the exhibition, reminding visitors that some of Korea’s Buddhist and Confucian traditions, and its courtly manners, thrive today amid Seoul’s sleek high-rises and Samsung Smartphones.

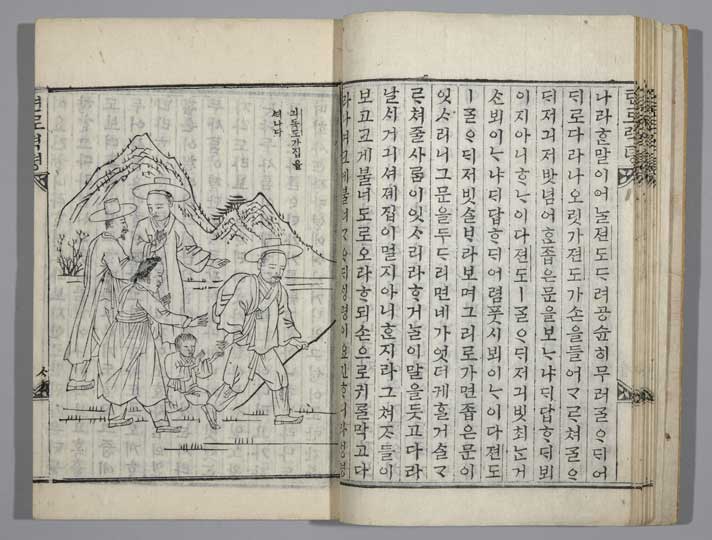

The show gives each exhibit its own space, lighting, and importance – a piercing portrait of a Confucian scholar, a gold-plated turtle-shaped royal seal, an elephant-shaped ritual vessel, a king’s poem in sweeping Chinese characters. An 1895 copy of Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress was the first entire English novel translated into Korean and printed in Hangul, the Korean phonetic script. But the Joseon glory is surely its ceramics, the epitome of elegance and simplicity. One star among many is a 16th-century porcelain bottle with a single strand of rope design (painted in iron before glazing) that wraps around the slim neck and winds down the bulbous body.

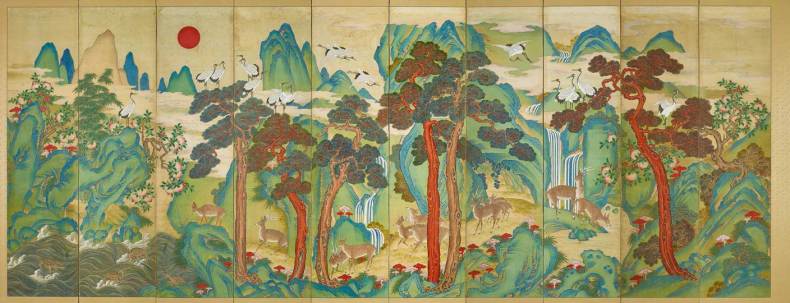

Well-funded by the Korean Foundation, the US’s National Endowment for the Humanities, The Exelon Foundation and others, the show has some helpful gadgets. A 1759 book about royal protocol for a wedding has been deftly transformed into a filmed procession projected onto a wall; a ten-fold screen depicting a landscape incorporating the Ten Longevity Symbols has a lively hands-on screen beside it to identify and explain each one. And an end-of-show computer encourages visitors to have their name translated into Hangul, which scholars deem one of the most intelligent scripts yet devised.

‘Treasures from Korea: Arts and Culture of the Joseon Dynasty, 1392–1910’ is at the Philadelphia Museum of Art until 26 May, and travels to Los Angeles County Museum of Art (29 June –28 September) and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 2 November – 11 January 2015).

Louise Nicholson explores the little-known artistic treasures produced in Korea during the Joseon Dynasty in the March issue of Apollo

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home