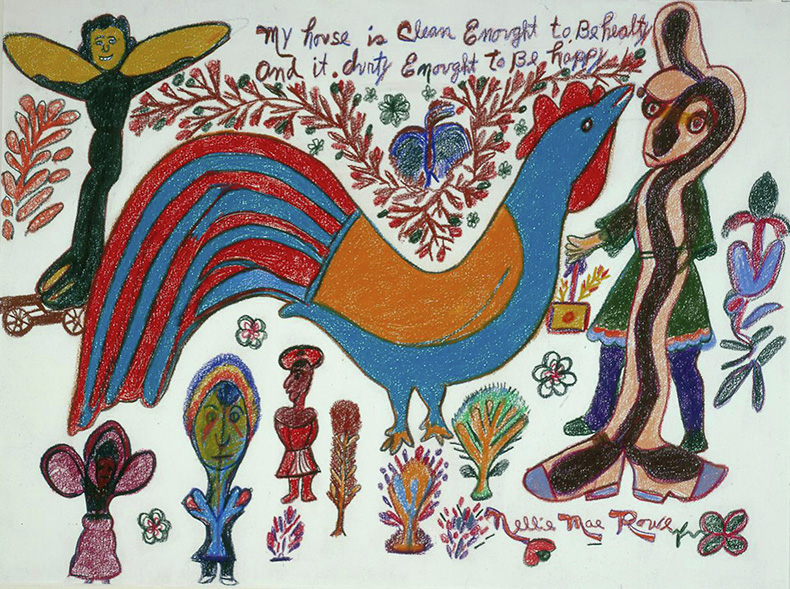

‘My House is Clean Enought to Be Healty and it Dirty Enought to Be Happy,’ wrote the artist Nellie Mae Rowe in one of her graphic tableaus rendered in crayon. The text is set above a large, brightly coloured cockerel and surrounded by illustrative flowers and shrubs, flighty birds and figures with their arms outstretched, in welcome or with wild abandon. The composition resembles a decorative affirmation hung in a kitchen above a hearth, but the sentiment is twisted, the cursive script rougher, the images looser.

Rowe knew about the domestic expectations placed on women, particularly African American women in the American South in the second half of the 20th century. Born in Georgia in 1900, she spent most of her life as a domestic help and the rest of it tending to husbands (there were two in succession). She came to art-making late – retired into it, summoning a dormant creative impulse that had been buried for more than 50 years. Perhaps more of a refrain than affirmation, My House is Clean Enought to Be Healty and it Dirty Enought to Be Happy (1978–82), like much of the artist’s work, takes pleasure in the debris and detritus of life and rails against societal expectation that had come to define Rowe’s own.

My House is Clean Enought to Be Healty and it Dirty Enought to Be Happy (1978–82), Nellie Mae Rowe. Photo: High Museum of Art, Atlanta; © 2022 Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

‘Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe’ at the Brooklyn Museum brings together more than 100 works from the final 15 generative years of Rowe’s life right up to her death in 1982, including compositional drawings and illustrative tableaus, graphic signatures and self-portraiture in vibrant crayons and markers, alongside three-dimensional dolls and miniature reproductions of Rowe’s infamous home, the ‘Playhouse’.

Untitled (Really Free!) (1967– 76), Nellie Mae Rowe. Photo: © High Museum of Art, Atlanta; © 2022 Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The phrase ‘Really Free’ is borrowed from another of Rowe’s graphic compositions Untitled (Really Free!) (1967–76), made from a page torn from an old pamphlet published by the Bible Society and inscribed with the same emancipatory impulse as her hearth-side refrain. Rowe knew, as we know, that no one is ‘really free’ until we are all free. But as a retired widow, those latter years offered some personal freedom in creative and personal expression.

Rowe was not politically active, but a personal politics was fundamental to her work – one operating at the intersection of race, gender and class. The Brooklyn Museum has framed the exhibition within a feminist context, which would risk putting words in Rowe’s mouth if the work wasn’t so bound up with these tacit markers of identity, not least womanhood. This is most apparent in Rowe’s self-portraiture where she is resolutely herself, albeit in various guises – at home, naked or in dress-up, with a walking stick or clutching a chicken.

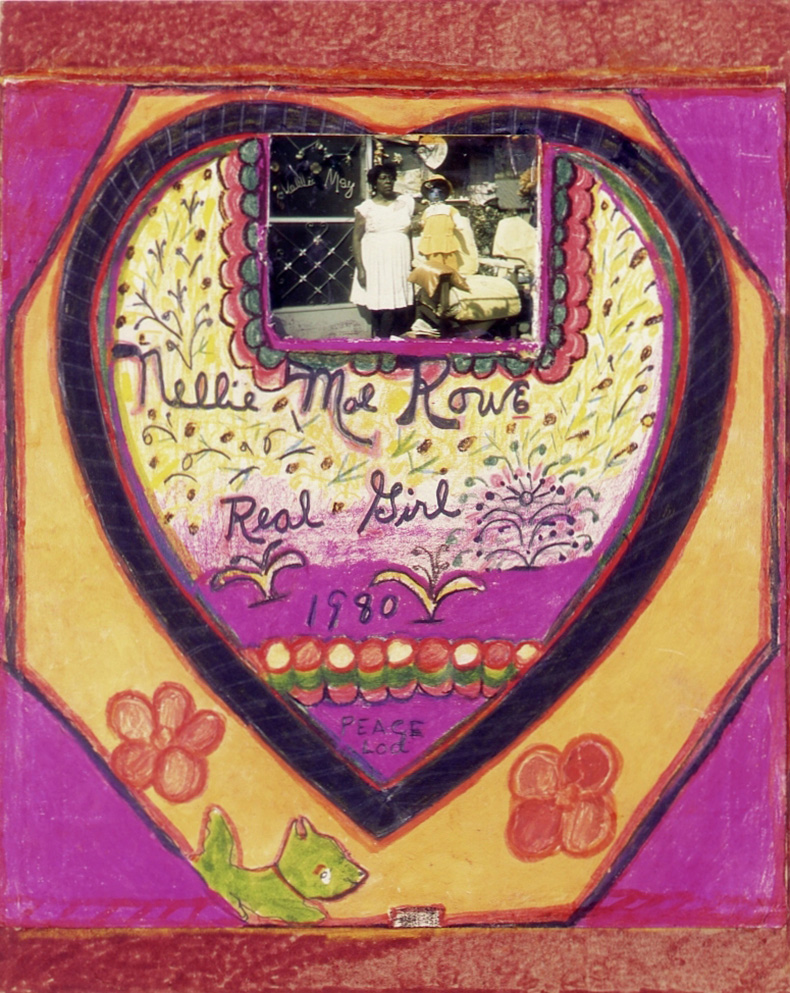

In Real Girl (1980), Rowe appears in a black and white photograph holding a doll and wearing a pressed white dress outside her home, in the Georgia sunlight. The photograph is framed by a love-heart hand-drawn onto cardboard and decorated with traditional tropes of femininity such as flowers and scalloped edges in bold shades of fuchsia and sunset yellow.

Below the photograph, and central to the image, are the words:

Nellie Mae Rowe

Real Girl

1980

Peace

God

Rowe told a reporter in 1979 ‘I am Black, and I love my Blackness,’ and in Real Girl, she challenges the precepts of femininity by putting her Blackness, her womanhood and spirituality in the frame as if she were saying ‘we are not really free, but I am really here.’ This feels radical anywhere but certainly in the Jim Crowe era South.

Real Girl (1980), Nellie Mae Rowe. Photo: High Museum of Art, Atlanta; © 2022 Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

When she wasn’t rendering her own image, Rowe wrote her name in elongated and spacious letters – the long tail of a serif ‘M’ for Mae, in Really Free fluted like a trumpet. Trumpets are loud and Rowe’s signature becomes more than mere provocation but an imperative, one that resembles the political tool of enumeration, used by the oppressed to lament the dead or incarcerated.

Rowe is often associated with the outsider art movement – a term coined in 1972 by art critic Roger Cardinal in reference to self-taught or so-called ‘naive’ artists living at the margins of society and removed from the art world. Rowe’s real freedom, the thing that nobody could contain, was the original insight of being a self-taught artist. Playful rather than whimsical, vivid and honest, her work is not shaped by the politics of institutional learning nor indebted to the canon or artistic movements. But this freedom came at a price – Rowe lamented her childhood spent tending the family farm when she could have been making art.

After years of serving others, Rowe sought out the emancipatory feeling of childhood – the one she never had – turning her home into a playhouse filled with cloth and yarn dolls, framed drawings, keepsakes and a yard strung with clotheslines and garlands. She garnered unwanted attention from local vandals and bigots, but also welcomed tourists, travellers and art enthusiasts; this enabled her to engage with the world on her own terms.

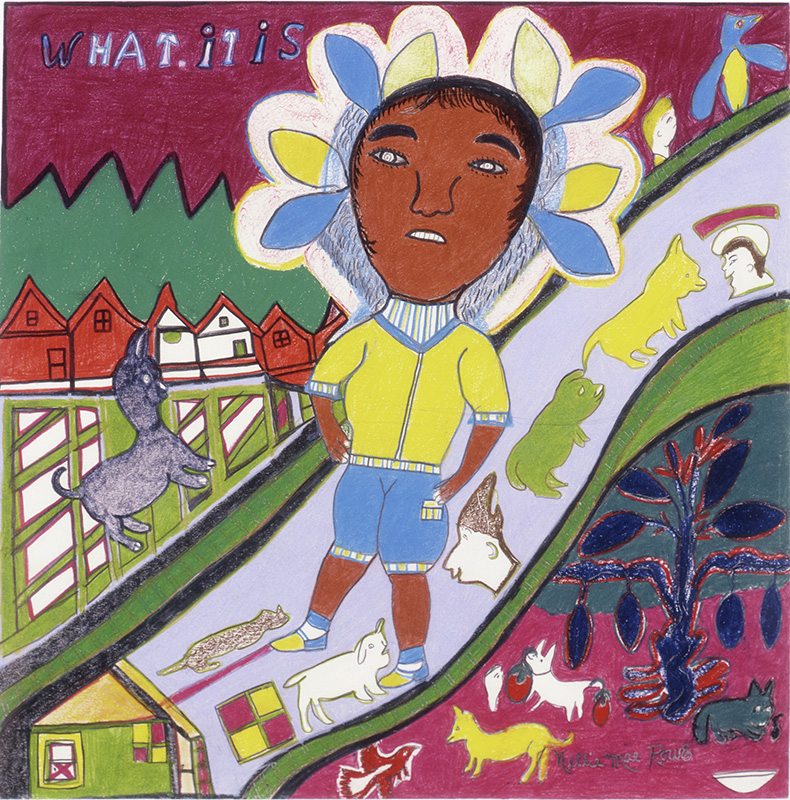

The beauty of Rowe’s work is in the ‘really’ rather than in the ‘free’, which she impresses on us through a refusal to yield – be it in colour or form or in the directness of meaning through text. And if there must be a notion of freedom within the work, it is a freedom from the harsh reality of domesticity or the redeployment of it in forms and spaces where scale, colour and composition slips through and beyond reality.

What It Is (1978–82), Nellie Mae Rowe. Photo: High Museum of Art, Atlanta; © 2022 Estate of Nellie Mae Rowe/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

‘Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe’ is at the Brooklyn Museum, New York until 2 January 2023.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home