From the December 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

When a digital artwork by the graphic artist Beeple sold for $69.3m at Christie’s in March 2021 – roughly the same price you’d expect to pay for a top-quality Rothko – the world suddenly became aware of non-fungible tokens (NFTs). Soon every arts journalist’s inbox was jammed with press notices about NFT ‘drops’, as releases of new works are called.

In September of this year, even the former ‘bad boy’ of British art, Damien Hirst, jumped on the bandwagon with an exhibition of his own NFT project, ‘The Currency’. Pace Gallery released its latest collection of NFTs on its platform, Pace Verso, in the same month, while Christie’s has launched an ‘on-chain’ marketplace, Christie’s 3.0. They are all capitalising on the fact that sales of art NFTs on the platforms that sell them – OpenSea, NFTX, Larva Labs, LooksRare, SuperRare, Rarible and Foundation – rose from almost nothing in January 2021 to $17bn in January 2022, according to Bloomberg.

An NFT is a piece of computer code, created using similar software to cryptocurrencies like bitcoin and ether. They all rely on blockchains – ‘distributed public ledgers’ that allow ownership of an asset to be verified across a worldwide network of individual computers without central control. In most cases the NFT is not the piece of art itself. Instead it ‘points’ to a digital file – anything from an artwork to a video, a recording or a design – that can be bought and sold using a cryptocurrency, usually ether. Because each NFT is unique, unlike a bitcoin, it allows the buyer to claim that they own the original digital work, however easily the image file itself can be copied.

But just as NFTs seemed to be booming, the bubble has burst. Sales of art NFTs in September stood at $466m, a 97 per cent fall since January this year. This mirrors the crash in the cryptocurrencies with which NFTs are connected. The value of bitcoin has fallen by more than 70 per cent to under $20,000 from its high of more than $69,000 in November 2021. The collapse of FTX throws the direction of cryptocurrencies even further into doubt. There are also signs of faltering auctions. At a recent NFT auction by Sotheby’s Hong Kong on 1 November, five of 21 lots failed to sell, while 10 went for less than their low estimate.

So are NFTs the flash in the pan that many suspect, or could they have longer-term cultural value?

‘I’m not unhappy that there has been a crypto and NFT crash, and that the hype is over,’ says Sabine Himmelsbach, the director of new media gallery the HEK in Basel. ‘Since the beginning, everybody just talked about the money and not about the quality of the work. In most cases, a JPEG, a GIF or a little video clip connected to an NFT is not very interesting.’ She says she is ‘much more interested in more conceptual approaches by artists who are delving into the inherent possibilities of the blockchain’ and work that critiques what she calls the ‘bro culture’ that pervades the NFT world. The HEK has just minted its first NFTs with veteran media, feminist and environmental artist Ursula Endlicher, who has been making digital art since the 1990s.

Jason Bailey – an artist and writer who came from the traditional art world but is also founder of ClubNFT, designed to protect collectors’ digital artworks – is an evangelist for what he calls ‘the interaction between digital technology and art’. He thinks the influx of ‘a lot of new people coming in, not necessarily with a background or understanding of art but a lot of enthusiasm’ is a cause for celebration.

Bailey points out that a plethora of different types of people are making NFTs, including trained artists who feel failed by the current art market. ‘There’s a global community of artists, many who aren’t making any money from the current art world system, who have come together and formed an entirely new market that in many cases is more equitable and empowering for them,’ he says. ‘There are a lot of people selling work for $10, $15, $20. That isn’t going to make the cover of ARTnews but, cumulatively, it’s a revolution.’

Installation of Hito Steyerl’s live computer simulation SocialSim 2020, at the Centre Pompidou, Paris, in 2021. Courtesy the artist, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York and Esther Schipper, Berlin; © Centre Pompidou / Bertrand Prévost

These opposing views may explain why the art world finds NFTs so confusing. They are made by many groups of people in many genres, from high art to pop culture. A lot of the most talked-about NFTs are based on cartoons, sci-fi imagery, psychedelia or surrealism. In many ways they are not so different from street art – another popular visual language with its own communities, codes and references that was briefly co-opted by the mainstream art world in the market boom of the mid 2000s.

Many makers come from graphic design, animation, programming, computer game design and other parts of the tech world. Most promote their work on social media platforms such as Twitter, Telegram and Discord. Beeple, who like many NFT artists is self-taught, had nearly two million followers on Instagram before his record-breaking Christie’s sale. He had sold NFTs before for about $100,000 each on the NFT platform Nifty Gateway.

Noah Davis, who was the contemporary specialist at Christie’s behind the $69m Beeple sale and is now brand lead at CryptoPunks, admitted to the New York Times last year that ‘some [NFTs] do look like they belong in a head shop, on a dorm wall or on a message board.’

Ironically, NFTs have their origin in the contemporary art world. In 2014 an artist and a technologist, Kevin McCoy and Anil Dash, created the first one, with the aim of protecting digital artists’ rights. McCoy, with his wife Jennifer, are well-established new media artists with work in the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the Museum of Fine Art, Houston. Last year Dash told the Atlantic that ‘the idea behind NFTs was, and is, profound. Technology should be enabling artists to exercise control over their work, to more easily sell it and to more strongly protect against others appropriating it without permission.’ But the dream, he wrote, ‘hasn’t yet come true’. As the article states, ‘tech-world opportunism struck again’.

New media art, as opposed to NFTs, has a long history. It goes back at least as far as Robert Rauschenberg’s 1966 Experiments in Art and Technology, which paired artists with engineers from Bell Telephone Laboratories. Bruce Nauman, Nam June Paik and Manfred Mohr were other early new media pioneers.

For decades, new media art was considered difficult and conceptual. Interest centred on a handful of specialist institutions, such as the ZKM in Karlsruhe and festivals like Ars Electronica in Linz. There was a flurry of museum exhibitions around the first dot-com boom, including ‘BitStreams’ and ‘Data Dynamics’, both at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, and ‘010101: Art in Technological Times’ at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, in 2001.

It is only in the past five years that artists such as Hito Steyerl, whose work draws on computer games, military technology and surveillance cameras, have come to mainstream prominence. Steyerl joins a handful artists such as Jon Rafman, Ian Cheng and Camille Henrot whose work uses and critiques contemporary technologies and has become a fixture on the international biennial circuit.

But now they are being joined by artists whose work has grown out of NFTs. bitforms, one of the longest-standing new media galleries in New York, recently signed two stars of the NFT world, Refik Anadol and Tyler Hobbs. Anadol, a Turkish-American artist, uses artificial intelligence to turn big data sets into immersive sensory experiences. Hobbs, a Texas-based painter, creates custom algorithms to generate refined abstract works of digital art. Meanwhile, Sarah Friend, a Berlin-based artist using NFTs, Minecraft and the internet, comments on NFT culture: her series of Lifeforms NFTs are only kept ‘alive’ if owners give them away within 90 days.

Alex Estorick, the editor-in-chief of Right Click Save, an online magazine designed to create a critical context around NFTs and new media art, says, ‘What we’ve seen this year is that the crypto and mainstream contemporary arts are merging. It is one of the benefits of the crypto crash that the hype and the argument that NFTs are really just a speculative vehicle has drained away.’

Despite the volatility of the crypto markets, NFTs are clearly here to stay. But the NFT art market seems to have offended

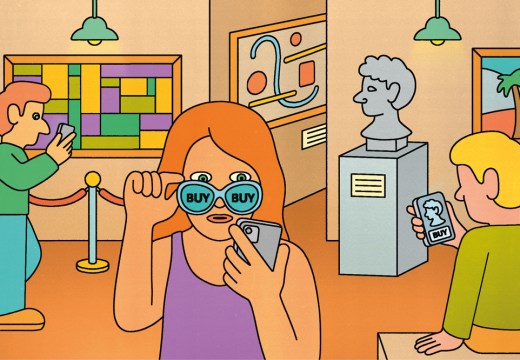

much of the traditional art world with its pop culture aesthetic, brazen commercialism and its ability to circumvent the traditional system. The huge prices paid for little-known and sometimes derivative artists has raised uncomfortable questions about the way art is valued.

But distrust runs both ways. Early NFT artist Robness spoke for many when he said that traditional art-market players ‘are only here because they saw the dollar signs. They weren’t here to support us from the beginning. It’s something I constantly remind new people in this [the NFT] space about,’ he told Right Click Save.

There are clearly millions of buyers for NFTs, and while most of the work is insignificant, the same is true for physical works of art. Perhaps NFTs can be seen as the latest development of new media art, as the best practitioners in both fields begin to cross over. Instead of dismissing, perhaps the traditional gatekeepers who decide the cultural value of art should apply their critical faculties and not just their marketing skills to digital art and NFTs. The NFT market is huge and although it only partially crosses into the mainstream art world, the possibilities to educate a completely new audience in fine art has never been greater.

From the December 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home