From the March 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In 1981, Rosalind Krauss took aim at a phenomenon she identified as ‘Autobiographical Picasso’. It was not the artist himself in her sights, but rather the version of him that had been created by historians such as William Rubin and John Richardson – men who ought to have known better – professing that ‘the turns and twists of the master’s private life’, all of what Krauss called those ‘sordid’ situations with his succession of wives and mistresses, could determine the reasons behind each of the many stylistic shifts over the artist’s long and protean career. This was gossip masquerading as art history – its exponents guilty of ‘exhort[ing] art-historical workers to fan out among the survivors of Picasso’s acquaintance’ and scrounge ‘the last scraps of personal information still outstanding before death prevents the remaining witnesses from appearing in court’. It was indicative of the broader reduction of art history to what Krauss memorably called ‘the insistent mouthing of proper names’.

This year, the 50th since his death, the name of Picasso is being mouthed more insistently than ever. Under the auspices of the culture ministries of France and Spain, no fewer than 50 exhibitions have been arranged as part of ‘Celebration Picasso 1973–2023’ across Europe and the United States. There are shows of the cubist works at the Met, the sculptures at the Guggenheim Bilbao, Picasso’s engagement with fellow artists, alive and dead, and above all a host of shows that zoom in on particular moments of his life, ranging from ‘Picasso 1906: The Turning Point’ at the Reina Sofia to ‘Picasso 1969–1972: The Beginning of the End’ at the Musée Picasso in Antibes.

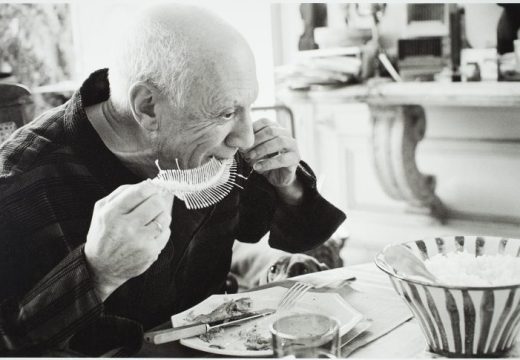

But if Autobiographical Picasso remains at large today, it is also true that he cuts something of a wounded figure. Where those uncomfortable, ‘sordid’ aspects of his character were once treated as necessary conditions of his genius, 21st-century audiences are – to put it mildly – not so sure. In Picasso, The Minotaur (2017), Sophie Chauveau painted a picture of the artist as an ‘ogre’ who ‘devoured his loved ones’ – and a ‘virus’ who ‘contaminated’ every artist of the 20th century. There is a certain irony here, in that Picasso’s detractors, by delving into his psychology – just as Rubin and Richardson, at least in Krauss’s estimation, had done before – are in a sense following the artist’s lead. He kept boxes and boxes of letters and diaries, intending to ‘leave to posterity the fullest possible documentation’, so that generations after him could piece together the progress of his thought. ‘You can’t just know the works of an artist,’ he once told Brassaï. ‘You also need to know when he made them, why, how, and in what circumstances.’ But for some, knowing who Picasso was has now become an argument not to know his works at all.

The Salon Jupiter at the Musée Picasso in Paris, whose interiors were selected as a suitable setting for works such as The Pipes of Pan (1922). Photo: © Musée national Picasso-Paris; © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2023

To these ‘attacks’, Cécile Debray, president of the Musée Picasso in Paris, has a straightforward answer: ‘We have to welcome the debate into the museum.’ When I arrive at the museum in early February, much of it is closed in preparation for ‘Picasso Celebration: the Collection in a New Light’, a temporary rehang arranged under the artistic direction of the fashion designer Paul Smith. Walls will be plastered with pages from old fashion mags, and elsewhere painted in stripes (naturally) – but there are also more pointed moments. Works by contemporary artists – among them Mickalene Thomas and the Congolese painter Chéri Samba – are called upon as means for viewers to reflect not only on Picasso’s global legacy, but also to consider difficult questions regarding his depiction of women and his borrowings from African art traditions. When I visit, an exhibition of works by Faith Ringgold has just opened on the ground floor. ‘Even for a museum dedicated to an artist who died 50 years ago,’ Debray says, ‘it is very important to maintain a link with living artists.’

Of course, the Musée Picasso remains inextricably tied to the biography of the artist for whom it is named. On 31 December 1968, its creation was set in motion when the law of dation, equivalent to the Acceptance-in-Lieu scheme in the UK, was passed. This was achieved by a government that had more than half an eye on the fabled hoard of the world’s most famous artist, then in his late eighties. And Picasso was indeed a hoarder. The inventory drawn up by auctioneer Maurice Rheims after Picasso’s death included more than 70,000 works of art. He sold works, even to museums, only reluctantly, preferring to keep them as reference points so that he could chart his progress. The same impulse led him to become an obsessive documenter of his public profile; in an age before Google Alerts, he signed up as early as 1917 to the press service Lit-tout, which sent him every article that was published about him for the rest of his long life.

Self-portrait (1901), Pablo Picasso. Musée national Picasso-Paris

After Picasso’s death, Jacqueline Roque, his last wife, and his four children agreed with Michel Guy, then the French culture minister, upon the creation of a museum dedicated to the artist. A committee was established by Dominique Bozo, the inaugural director, to thresh from the vast inventory a working collection. After three years, they had chosen 203 paintings, 158 sculptures, and several thousand other works including prints, drawings, ceramics and books. Though these have since been augmented by further gifts and bequests – including, notably, more than 400 pieces that belonged to Dora Maar in 1998, and 100 that belonged to Brassaï in 2011 – it is the founding collection that still forms the core of the museum.

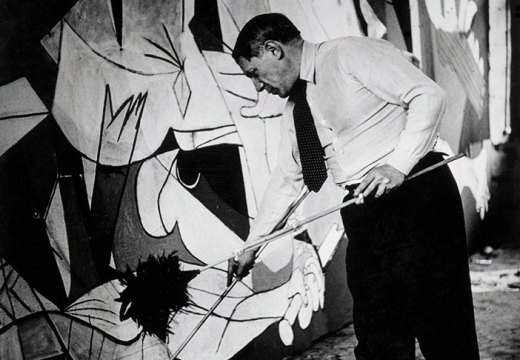

‘The collection was created in a singular way, at a singular time,’ Debray says. ‘It is very coherent – assembled to form a journey.’ But if, in a sense, it has been shaped by curatorial eyes, it could not help but take its cues from Picasso himself. ‘He did not try to organise his succession in an administrative manner,’ Debray suggests, ‘but he knowingly preserved the works which were most intimate to him – works that are linked to his history, to the disappearance of a friend, for instance. He kept these with him – so that he could see where he was going. And this is what allows us, with the museum, to enter into the intimacy of creation, to understand how Picasso worked.’ ‘There are no very big and very great masterpieces in the collection,’ Debray acknowledges – museums did manage to prise pieces such as Guernica (1937) and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) from the artist’s grip. But instead, the Musée Picasso has an abundance of transitional works – paintings or sculptures that mark the culmination of one period or the beginning of the next. It has the sober, sentimental Barefoot Girl (1895), a painting that shows he’d pretty much mastered the naturalism of Spanish tradition before turning 14. It has his remarkable Self-Portrait (1901) – a rhapsody in blue, the young painter’s face gaunt and aged beyond his young years. Considered by many to be an elegy for Carlos Casagemas, Picasso’s close Catalan friend who had killed himself over a failed love affair, it is an emphatic announcement of the beginnings of Picasso’s Blue Period that would define his next three years.

In the world’s great museums there is no shortage of masterpieces from the peak of analytical cubism, around 1912 – there are a few down the road in the Pompidou. But there is nowhere better than the Musée Picasso to grasp, visually, the evolution of the movement. Perhaps there is even no better single work in this regard than The Sacré-Coeur, a sketchy oil painting completed in the winter of 1909–10, situated at the midway point of Picasso’s engagement with late Cézanne – the Montmartre monument broken down into ‘the sphere, the cone, the cylinder’ – and the more comprehensive fragmentation of perspective that would follow.

The museum has works such as the Portrait of Olga in an Armchair (1918), among the earliest realisations of the Ingres-inflected classicism that would characterise the immediate post-war years – as well as The Pipes of Pan (1922), one of the fullest (and strangest) realisations of this period, with its two loin-clothed youths, pictured before an empty seascape worthy of De Chirico, appearing at one and the same time to move with the music of the pipes and to be frozen in statuesque stillness. It has lustful, linear paintings of the 1930s; it has works from his declining years, the long denouement, when figures, forms and ideas from the past half century and more would resurface like restless spirits, attenuated but insistent. It has Picasso’s earliest known sculpture, Seated Woman (1902) in clay, as well as perhaps his most famous: the Bull’s Head (1942) he improvised from a bicycle’s seat and handlebars, a metamorphosis described by Roland Penrose as ‘astonishingly complete’.

Bull’s Head (1942), Pablo Picasso. Musée national Picasso-Paris

In short, the museum has an embarrassment of riches to deploy – and the question of how best to deploy them is a thorny one. At the Hôtel Salé – the 17th-century townhouse chosen as the site of the museum, for the balance it struck between architectural grandness and domesticity of scale – the last major rehang took place in 2014, after a comprehensive restoration and renovation project that refitted the interiors and gave the museum a new entrance hall. The itinerary has since been chronological, arranged across three floors. In tracing the contours of a life through art the museum is bound, in a sense, to be a kind of biography; letters, diaries and other archival sources (of which the museum has more than 200,000) were mobilised throughout to give an added sense of intimacy to the displays.

But Debray points out that the museum is also much more than this. It enables a full appreciation of the ‘depth and subtlety of Picasso’s plastic thought’, on the one hand. And, seen with the right eyes, the wealth of archival resources can open up a much broader understanding of Picasso’s role in the life of the 20th century. Delving into his correspondence with Gertrude Stein, or Giacometti, one can recover a sense of how ideas were shaped and shared by the leading members of the avant-garde. Both of these elements – style and social context – are what Krauss in the same essay calls the ‘transpersonal’: tools to counteract the effects of monolithic biography in art history. And perhaps what is most impressive about Debray’s tenure as president of this singular museum is how she has brought the biographical weight of the collection of which she has taken charge to bear on the transpersonal, and vice versa.

‘We’re going to bring back complexity,’ Debray says. Her career to date has equipped her well for the complexities with which Picasso confronts us today. As chief curator in charge of the Pompidou’s modern collections from 2008–17, she staged major shows on Matisse, Duchamp and Derain. Then, shortly after becoming director of the Musée de l’Orangerie in 2017, she was instrumental in arranging the landmark exhibition ‘Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today’, which grew out of the research of the American scholar Denise Murrell (now a curator at the Met). In 2017–18, she staged ‘Dada Africa’; a scholarly reassessment of the ways in which Dada artists appropriated non-Western forms in their reaction against Western tradition, this was a show that did not shy away from the legacy of colonialism that guided these artists’ encounter with Africa, but nor did it seek to castigate them for it. Debray is, in short, equally well versed in the canonical presentation of art history, and in newer, social forms of the discipline that attempt to crack open the canon with new kinds of storytelling. She is also capable of treading lightly on dangerous ground.

‘The future,’ she tells me, ‘is about learning to wear the legacy of Picasso in the 21st century. How do you look at Picasso – as a misogynist, someone who does not behave appropriately according to our current criteria – and not just throw him in the trash?’ The programme she has begun to instigate suggests that the answer lies in first of all acknowledging that there are many answers, and in listening to them all as attentively as possible. The chronological presentation will remain – and Debray says that it is important to counteract ‘caricaturised’ versions of the artist’s biography – but it is being supplemented by responses that invite critical reflection on the story of Picasso as it was written last century. Last year, the museum staged an exhibition by Orlan – a series of hybrid photographs, titled Weeping Women Are Angry, that offered a feminist take on Dora Maar’s photographs of (and purported modelling for) Picasso during the creation of Guernica. Debray has not settled on any one idea for the future. She hopes to show young Jackson Pollock, ‘who followed Picasso’, or ‘Louise Bourgeois, who is like a female counterpart to his vision of sexuality’. ‘Maybe we can have a project with Harlem Renaissance artists of the 1920s – artists who have a mixed relationship with the example of Picasso,’ she says.

Picasso’s Studio: The French Collection Part I, #7 (1991), Faith Ringgold. Worcester Art Museum. Courtesy ACA Galleries, New York 2023; © Faith Ringgold/ARS, NY and DACS, London

That the majority of the Musée Picasso is closed for the Paul Smith hang when I arrive means that, on this visit, the only insight into the artist I gain is through the eyes of Faith Ringgold on the ground floor. But in some ways, this is apt. The exhibition offers a broad survey of Ringgold’s career, but it pivots upon two works. One is Picasso’s Studio (1991) – part of The French Collection, a series of tapestries that imagine the life of the fictional Black artist Willia Marie Simone, carving out a career in early 20th-century Paris. Picasso, bald and shirtless with a pronounced paunch, is painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Simone is posing, while behind her on the wall hang a number of African masks. In text that appears on the borders of the tapestry, they begin to speak to her: ‘Do not be disturbed by the power of the artist’, they say. ‘The power he has is available to you […] We don’t want him to hear us talking, but we just want to let you know you don’t have to give up nothing.’ Here, Picasso is firmly a man of his time – taking cues from an African tradition he cannot understand. The other work is American People Series #20: Die (1967), a terrifying and grisly painting of civil uprisings and the precarity of Black life in the United States. It is also a direct and frank homage to Guernica, which Ringgold studied extensively – and as such, a testament to the ability of that painting to transcend its historical moment and speak of the timeless horror of violence. Together, these two works by Ringgold are proof that Picasso’s legacy remains as conflicted as ever – but also that conflict, as Picasso knew only too well, can be terrifically productive.

From the March 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home