In February 1949, ‘La collezione Guggenheim’ opened at the Strozzina, the gallery in the cellars of the Palazzo Strozzi. The 157 works were shown in the subterranean space, used as an air-raid shelter in the war, which had seen the destruction of all bridges over the Arno except the Ponte Vecchio. Despite the title, the exhibition consisted of pieces only from the collection of Peggy Guggenheim, who apparently found the dank location perplexing – some critics dismissed it as her baraccone (funfair). A year earlier, she had exhibited two-thirds of them in Florence in the Greek pavilion at the Venice Biennale. ‘I felt like a whole country,’ Peggy exulted, proud to be introducing Pollock, Gorky, and Rothko to Europe for the first time. In 1949 she would immigrate to Italy, buying her famous palazzo on the Grand Canal, where she would also transform the cellars into an exhibition space.

Peggy Guggenheim with earrings made for her by Alexander Calder, 1950s. Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. Photo Archivio Cameraphoto Epoche

In ‘From Kandinsky to Pollock’, 25 of the works shown at the Strozzina have returned, now exhibited upstairs in the voluminous rooms of the piano nobile: pieces by Picasso, Brancusi, Klee, Giacometti, Dalí, Ernst, Duchamp, and Pollock. These are fleshed out with works from her uncle’s larger collection to create a comprehensive and impressive survey of European and American avant-gardes. The exhibition opens with a juxtaposition of a photograph of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, ‘a temple of spirit’ designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, and another of Art of This Century, Peggy’s bohemian Manhattan gallery with theatrical interiors by Frederick Kiesler. Between them, as a sort of bridge, is Dominant Curve by Kandinsky, a 1936 painting that Peggy owned, but then sold, and which Solomon later acquired. They were both collectors and patrons who defined modernism but, in the fusing of collections here, their differences are muted.

After her father died on the Titanic, Peggy inherited $450,000, but she was never ‘madly, madly, madly rich’ like her uncle and lacked his buying power. She considered herself the ‘enfant terrible’ of the family. But, having lived in Paris where she was (unhappily) married to the artist Laurence Vail, whom she called the ‘King of Bohemia’, she counted many of those she collected as friends and sometimes lovers. Marcel Duchamp was one of her most trusted advisors (his first Boîte-en-valise was dedicated to her), and André Breton an occasional scout. Solomon, on the other hand, was guided by his mistress, the eccentric and autocratic Baroness Hilla Rebay, who had a Steineresque faith in the spiritual value of non-objective art. In 1937, when Peggy opened Guggenheim Jeune, her gallery in London, Rebay accused her of sullying the family name, ‘which stands for an ideal in art’, with ‘some small shop’ that would ‘peddle mediocrity’.

Peggy Guggenheim (1945), André Kertész (1894–1985). Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

In turn, Peggy and her then-husband Max Ernst visited her uncle’s Museum of Non-Objective Painting in New York, which she considered ‘a joke…atrocious’. It showed a preponderance of paintings by Rudolf Bauer (the artist who had replaced Kandinsky in Rebay’s affections), which were shown in ugly gilded frames, with Bach piped into the space to help elevate the canvases into what Rebay referred to as ‘the cosmic beyond’. (Peggy did, however, acknowledge the fine collection of Picasso, Chagall, Klee, and Robert Delaunay that she saw in her uncle’s apartment at the Plaza Hotel.) Peggy mischievously referred to Solomon Guggenheim’s later museum, with its spiralling ramp, as her ‘uncle’s garage’.

The Strozzi exhibition is curated by Luca Massimo Barbero, who works at the Guggenheim in Venice, and Peggy is very much the star. We don’t see much of Solomon but there are photographs of Peggy in her Venetian boudoir, decorated with a bedhead in sterling silver by Alexander Calder and Francis Bacon’s Study for Chimpanzee, a streak of fur against a Schiaparelli pink background; of her entertaining friends in her palazzo crammed with art, and photographed in a mirror by André Kertész behind the mushroom cloud-shaped shadow cast by one of Laurence Vail’s bottle sculptures, an effect cleverly recreated here using the original. There are 18 Pollocks on display (Peggy discovered him when he was a carpenter working in her uncle’s museum), and another room of Rothko, whose work she was one of the first to show, a dark space in which the canvases glow as if phosphorescent. There are also works by the Italian artists she came to love: Mirko Basaldella, Tancredi Parmeggiani, and Emilio Vedova.

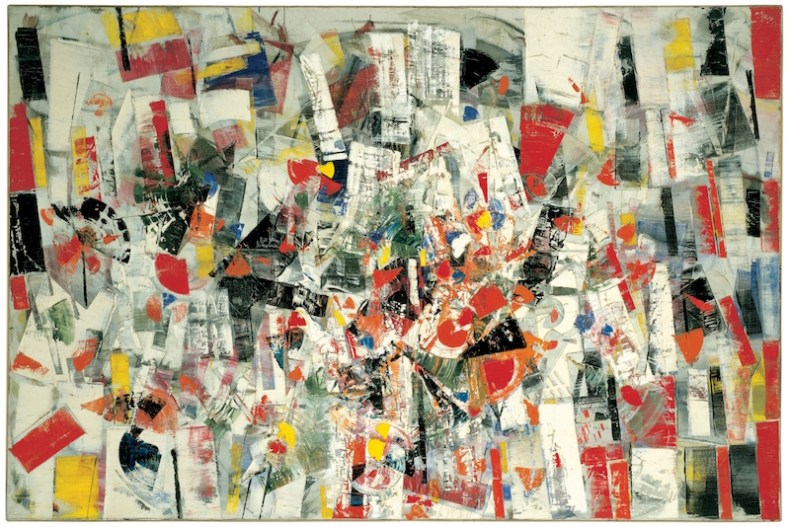

Composition (1955), Tancredi Parmeggiani (1927–64). Peggy Guggenheim Collection. Photo: David Heald

Peggy started collecting seriously in 1940 when, armed with a famous shopping list drawn up by Herbert Read, with whom she hoped to start a museum of modern art in London, her motto became: ‘a picture a day’. She acquired 63 works in six months, never having to bargain because, on the eve of the war, they were all ‘ridiculously cheap’. (She got the bulk of her collection for $40,000.) She acquired a Léger on the day Hitler invaded Norway, and Brancusi’s Bird in Space as the Germans marched on Paris. Artists keen to liquidate assets queued up for her patronage, and she sometimes even bought pieces from bed. Only Picasso refused her: ‘The lingerie department is on the second floor,’ he said dismissively, when she visited his studio. In trying to salvage modern art from war-torn Europe, she sometimes competed with Rebay, who even managed to buy works from the Nazi’s Degenerate Art exhibition.

Roaring Lion II (1956), Mirko Basaldella (1910–69). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo: David Heald

The Strozzi exhibition is perhaps really a story of the competitive battle between these two figures with outsized personalities, but the Guggenheim empire prefers to propagate a more harmonious version of the family history. After Solomon’s death, James Johnson Sweeney, who had worked as an advisor to Peggy in the 1940s, took over from Rebay as director of the Guggenheim Museum and in 1969 persuaded her to show her collection there. She remarked that her uncle would probably be turning in his grave if he knew. A decade later, when she died at 81, she left her collection to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation. ‘It was rather a joke,’ she said of the bequest and the condition that it stayed in Venice, ‘since I wasn’t on very good terms with my uncle.’

‘From Kandinsky to Pollock: The Art of the Guggenheim Collections is at the Palazzo Strozzi, Florence until 24 July.

From the June issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home