Introducing Rakewell, Apollo’s wandering eye on the art world. Look out for regular posts taking a rakish perspective on art and museum stories

When not lurking in museums or trudging round art fairs, Rakewell has been known to enjoy the odd brush with nature – in a carefully controlled environment. And the Apollo office provides the perfect opportunity, located as it is near St James’s Park. The highlight of a lunchtime stroll is always a sighting of the park’s three pelicans. There have been pelicans in St James’s Park since 1664 when the Russian ambassador to London presented Charles II with two grey or Dalmatian pelicans (Pelecanus crispus). Last Monday (15 July), their modern-day successors Isla, Tiffany and Gargi were joined by a trio of Great Whites (Pelecanus onocrotalus) called Sun, Moon and Star – all the way from Prague Zoo. Rakewell has caught a few glimpses in the last week and looks forward to many more.

The three existing pelicans on Pelican Rock in the middle of St James’s Park, London. Photo: Paula Redmond; courtesy The Royal Parks

In the meantime, it seems only fitting for Rakewell to celebrate the excellent creature’s appearances in art through the ages. In medieval Christianity, the pelican’s self-sacrificial feeding of her young makes her an obvious stand-in for Christ – after piercing her side with her beak, the blood that flows revives the chicks and she promptly dies. Frequently depicted in medieval bestiaries, the pelican can also be found on crosses, altars and doorways – and even topping a sundial of 1581 in Corpus Christi College, Oxford.

Pelican sundial at Corpus Christi College, Oxford. Photo: Howard Hotson; used under Creative Commons licence 4.0

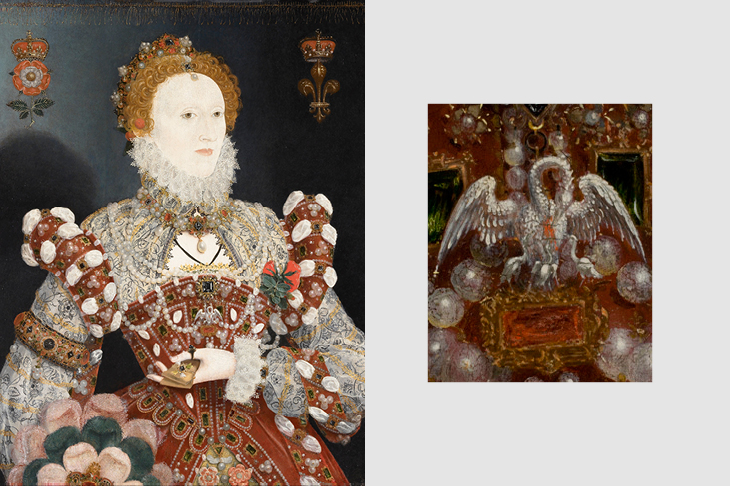

When Elizabeth I had herself painted wearing a pendant in the shape of a pelican, she was certainly casting herself as the mother of the nation – but perhaps not hinting at a gory end.

The ‘Pelican’ Portrait (c. 1573–75), Nicholas Hilliard. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool

More sunnily still, there is Edward Lear’s poem ‘The Pelican Chorus’ about a Nile-dwelling duo who marry their daughter to the King of the Cranes.

Lear’s proof illustration for ‘The Pelican Chorus’, in Laughable Lyrics (1877). Houghton Library, Harvard University

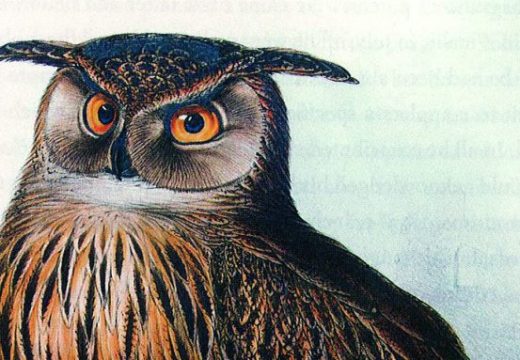

The more ornithologically minded may prefer Lear’s illustrations for John Gould’s Birds of Europe, but who could resist the refrain of ‘The Pelican Chorus’?

Ploffskin, Pluffskin, Pelican jee!

We think no Birds so happy as we!

Plumpskin, Ploshkin, Pelican jill!

We think so then, and we thought so still!

Got a story for Rakewell? Get in touch at rakewell@apollomag.com or via @Rakewelltweets.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home