In around 1840, when he first saw a daguerreotype, Paul Delaroche declared: ‘From today, painting is dead.’ His painting of Cromwell, the great iconoclast, lifting a coffin lid to gaze at Charles I, the great collector and commissioner of Rubens and Van Dyck, captures something of this melancholy. Ever since the birth of photography threw the discipline into crisis, or freed it from its mimetic obligations, artists have declared ‘the end of painting’, seen as a conservative and obsolete medium in the face of technological change. Ad Reinhardt with his black monochromes claimed to be making ‘the last paintings which anyone could paint’; Gerhard Richter once said that painting was ‘pure idiocy’; Joseph Beuys told his students to ‘stop painting’, pushing them to conceptual art. One of these disciples, Jörg Immendorff, scrawled ‘Hört auf zu malen’ (‘Stop painting’) on a canvas in a gesture that the artist Peter Fischli, the curator of this exhibition, calls an ‘act of commando refusal’.

Installation view of Wo stehst du mit deiner Kunst, Kollege? (1973) by Jörg Immendorff in ‘Stop Painting’ at the Fondazione Prada in Venice. Photo: Marco Cappelletti; courtesy Fondazione Prada

Despite all the obstacles, painting has risen like Lazarus: ‘a very lively and strong knock knock knock came out of the black painted coffin,’ Fischli writes. His exhibition, staged in the grand Ca’ Corner della Regina, against a backdrop of baroque frescoes, is, in the artist’s description, a ‘kaleidoscope of repudiated gestures, including the critique of those repudiated gestures’. Floating white walls punch through the doorways of the space and are crammed with the art of rebellion and refusal. At the entrance to the exhibition is Immendorff’s Wo stehst du mit deiner Kunst, Kollege? (‘Which side are you on with your art, colleague?’, 1973), showing an artist in front of a blank canvas in the academy, while another bursts in, inviting him to participate in a street protest. In 1963 Henry Flynt picketed MoMA with signs reading ‘DESTROY ART! NO MORE ART!’ Painters such as Daniel Buren, with his striped placards (Seven Ballets in Manhattan, 1975), responded by taking their work out of the gallery into the real world, making the city its frame. Despite all the self-conscious iconoclasm, this is a show about the love of painting.

Fischli and his long-term collaborator David Weiss (who died in 2012) were known more for their deliberately banal photography (800 Views of Airports) than their painting. However, for their retrospective at Tate Modern in 2006 they created a trompe l’oeil version of their own studio, with sculpted paintbrushes and pizza boxes that were meticulously painted, in homage to Warhol’s Brillo boxes. Fischli contemplated constructing ‘Stop Painting’ around five crises or ruptures, but rejected the idea as too neat, preferring to abandon chronology to present thematic clusters of art in rooms with titles such as ‘Delirium of Negation’. The resulting juxtapositions and connections spark and fizzle, reminding me of Fischli and Weiss’s film The Way Things Go (1987), a 30-minute chain reaction involving spinning tyres, boiling kettles, burning candles, tipping buckets and bursting balloons, each a trigger in a series of slapstick, controlled catastrophes.

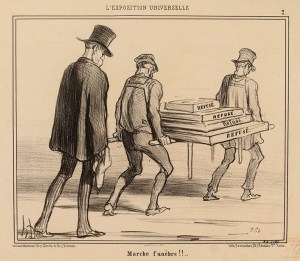

Marche funèbre!!…No. 2 (L’Exposition Universelle) (1855), Honoré Daumier. Musée Carnavalet – Historie de Paris, Paris

Dix-neuf petits tableaux en pile (1973), Marcel Broodthaers. Private collection. Photo: Todd-White Art Photography; courtesy Simon Lee Gallery; © Marcel Broodthaers, by SIAE 2021 Merlin

The ‘Die Hard’ section features a lithograph of 1855 by Honoré Daumier showing a dejected painter leaving the Exposition Universelle with a stack of rejected canvases, each stamped Refusé, which his friends carry as if in a funeral cortège. Alongside is Marcel Broodthaers’ Dix-neuf petits tableaux en pile (1973), which makes a Juddlike sculpture out of canvases of diminishing size, showing what Fischli calls an ‘empathetic nostalgia’ for painting, even among the avant-garde. Kurt Schwitters, for example, deconstructed the idea of painting with his three-dimensional collages, made from detritus, but privately he continued to paint very traditional still lifes alongside. Martin Kippenberger piled several of his early paintings inside an Orgone Energy Accumulator as if to recharge them with libidinous energy.

Clement Greenberg decreed that artists should explore the self-referential autonomy of painting, and its essential flatness, but the works on show question his attempt to create any continuity with the art of the past. A film of Bruce Nauman’s performance, Untitled (Flour Arrangements) of 1967, in which he moved flour around his studio floor for a month, shoots him from above as Hans Namuth did Jackson Pollock in 1950. Lynda Benglis pours liquid latex directly on to the floor in her own version of Abstract Expressionism, and Morag Keil’s Piss Paintings (2014) parody Pollock’s ‘drip’ method. Others attack the canvas with murderous intent. We see Lucio Fontana slashing and puncturing, to create ‘“openings” into space’, an aggressive gesture echoed by Dadamaino and Niki de Saint Phalle, who fires at the target with a rifle in her Shooting Pictures series. David Hammons shrouds his painting in found plastic sheeting, allowing us only occasional glimpses, like wounds, through its randomly placed tears and holes.

Arthur Danto, in his reflections on ‘The End of Art’, argues that photography led 20th-century artists to abandon any attempt to imitate nature and explore instead the question of art’s identity, leading to an era in which anything goes. Painting survived as the past was recycled and repackaged to satisfy the demands of the market and its appetite for ‘the illusion of unending novelty’. This capitalist triumph of painting, as a rapacious and tradeable commodity, is represented here by Warhol’s BMW Art Car of 1979, a blur of speed and colour, which the artist signed with his finger in wet paint. Nevertheless, ‘Stop Painting’ is infused with a celebration of the materiality of paint, of the artist at work, as seen in Jean-Frédéric Schnyder’s enormous quilt, each rectangle made of a rag used to wipe his brushes, and Michelangelo Pistoletto’s paint-spattered boiler suit and boots.

iPhone 11 (2019–20), Leidy Churchman. Collection Terry Winters. © Matthew Marks Gallery; © Leidy Churchman

On the ground floor, Fischli has chosen to present a 1:8 working model of the exhibition, which gives an illusion of curatorial omnipotence, while a recited text is accompanied by a slideshow, taking visitors through the development of the show with an entertaining scroll of images through the artist’s phone. Indeed, the smartphone, Fischli ruminates, has led to a new crisis for painting, but one that also gives it a radiant power. On display is Leidy Churchman’s painting iPhone 11 (2019–20), with its three lenses, as well as Morag Keil’s Big Brother Eyes (2018), each one containing the squared reflection of a phone or computer screen in its iris. Images (including of paintings) ‘move around as illuminated files on screens driven by algorithms’, Fischli observes. ‘What is this doing to images, and, even more worth considering, what is this doing to us?’

‘Stop Painting: An Exhibition by Peter Fischli’ is at the Fondazione Prada, Venice until 21 November.

From the July/August 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home