From the October 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

At the still heart of the painting, Pan’s ruddy grin and gilded torso, a buff embodiment of mischief. His empty eyes look down the arm of a nymph, across her chest, down her other arm, over fingers that trail across the top of a flower-filled basket, almost into the mouth of a putto. The diagonal of her arm continues into the smiling eyes of a boy, down his back, over the curve of his buttocks and his leg (his hip nudged by a drunken satyr’s hoof), where his heel marks the edge of the painting. Follow the same flowing line back up into the centre of the action, past Pan’s horns, to the dark silhouette of a hill that creates a backdrop for the left side of the picture. Perpendicular to this main diagonal, a reveller blows a long trumpet, animating a perpetual dance of delight.

This description of Nicolas Poussin’s The Triumph of Pan (1636) is an attempt to relive an experience I had about 25 years ago as I stood awestruck before the picture in the National Gallery, eyes jitterbugging across the canvas. Before this encounter, I was drawn to the earthier melodrama of Caravaggio, or Titian’s colours, or anything from Venice. But here was Poussin the cool classicist – who hated Caravaggio’s work – having a blast in Arcadia. Even the goat looks amused. Amid the blocks of colour and interlocking forms there are beguiling details – a tambourine, pan pipes, abandoned masks, a bowl glistening with red wine, nymphs and satyrs in ribald play: all the paraphernalia of a Dionysian romp, as I found out later. What struck me at the time was the immediate awareness of the flagrant, structured artificiality of the composition and all the internal rhymes. Poussin wasn’t stiff and dull but wild and witty. Entranced by The Triumph of Pan and by A Bacchanalian Revel before a Term (1632–33), not to mention that brilliant depiction of cascading space and rippling awareness, Landscape with a Man Killed by a Snake (1648), I became a poussiniste.

The Triumph of Pan (1636), Nicolas Poussin. The National Gallery, London

The Poussin fan club can feel surprisingly empty. Imagine a musicologist who dismisses Monteverdi as an old bore yet loves to kick back with The Eagles.That’s how I felt a couple of years ago about a museum curator who dismissed Poussin a few minutes after exalting a present-day painter of easy-listening landscapes. The curator didn’t offer a considered argument, and the comparison, perhaps unfair, is mine. Poussin will always look stern and forbidding to a lot of viewers. Even though I think that’s a misreading of the artist, I can’t deny that a lot of his work does look mannered and absurd, even campy. One glance at the ornate wonderland and Who’s Who of Ovid, The Realm of Flora (1630–31), would be enough to put off anyone who prefers a bit of naturalism. But part of the fun in looking at Poussin is deciphering all the stories and revelling in his complexities. When I first saw The Triumph of Pan, I fell for its form, buoyed in part by my interest in pastoral poetry. Only afterwards did I start to figure out some of the references – and learn that there isn’t a known textual source for the painting. In The Sight of Death, T.J. Clark recorded his reactions to Poussin’s Landscape with a Man Killed by a Snake and Landscape with a Calm (1650–51) over months, measuring his understanding against his moods, the light in the gallery and other factors. Poussin is worth looking at not only art historically (there’s plenty of superb scholarship) but as a peer, an artist of the early modern era whose paintings offer an analogue of complex awareness.

So where do we find ourselves while looking at a highly formalised vision of ancient Greece painted by a middle-aged French artist living in Rome in the early 17th century? What kind of experience – palpable, immediate experience, the way we experience contemporary art – if any, will we discover in other paintings by Poussin? Rubens is fun and fleshy, Caravaggio has his hot-blooded bravura. Artemisia Gentileschi, Poussin’s almost exact contemporary, is fiery and brilliant. Poussin is different. Standing before one of his paintings, even a Bacchanalian frenzy, you might feel the presence of a demanding, patient and sceptical temperament. Most of his paintings are richly allusive, overflowing with myth and history. But simultaneous to the more or less conventional iconography that we can decipher while looking at the pictures, it’s worth remembering that the artist often worked out his compositions with doll-like figures on a miniature stage. He conceived his paintings as an analogue of spatial awareness, playing out how the human body responds to its immediate setting, whether natural or architectural. The paintings conjure an image of embodied thought that is remarkable – and, I think, often overlooked. The notion of ‘embodied thought’ is a modern one, positing that human consciousness is inseparable from awareness of one’s body and environment. And I think this is a neglected element of Poussin’s greatness: he has a radical capacity to conjure in a painting – and to transfer into the viewer – a sensation of complex awareness.

The Realm of Flora (1630–31), Nicolas Poussin. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Photo: Elke Estel/Hans-Peter Klut; © bpk/Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

If Poussin’s biography is undramatic, his struggles as an artist seem almost modern, even relatable. After escaping his provincial hometown of Les Andelys, Normandy, in his late teens, he spent about a decade in Paris, making two failed attempts to move to Rome before finally arriving in 1624, at the age of 30. Spurned by the church after a single commission – The Martyrdom of St Erasmus (1628–29) hangs in the Vatican – and suffering from a sense of isolation and a dose of syphilis, he married a French chef’s daughter, whose family had nursed him back to health, and started to forge relationships with private collectors. When he painted The Triumph of Pan, he had been relatively settled and successful for a few years, and we find him at his most lively after a rough and unsteady first five or six years in Rome. Now in his late 30s and early 40s, and surrounded by a group of generous, likeminded patrons, he had achieved a degree of autonomy, both financial and intellectual. If Poussin had died at Caravaggio’s age, or before he painted his Bacchanals, the Poussin fan club would scarcely exist. But through an extraordinary body of work that he created through the early and mid 1630s, including The Realm of Flora and The Triumph of Bacchus (1635–36), as well as Dance to the Music of Time (1634) and the recently reattributed The Triumph of Silenus (1637), all included in the National Gallery’s new exhibition ‘Poussin and the Dance’ (9 October–2 January 2022), he laid the foundations for a life as an independent artist.

Back to the immediate experience of looking at one of Poussin’s parties – or, in the case of The Adoration of the Golden Calf (1633–34), a party interrupted. The Triumph of Pan offers an experience akin to looking across a dance floor when, for a split second, a group of limbs snaps into pictorial form. The painting offers a sculptural, embodied depiction of suspended time, where a sense of the fragmented multiplicity of experience becomes briefly legible. The Adoration of the Golden Calf brings this vision to life with symphonic force. As Moses descends from Mount Sinai in the upper left of the painting, furious about the partying idolaters and ready to smash the stone tablet in protest, his brother Aaron presents his golden calf to a crowd of worshippers. Beneath the calf, a group of dancers (the same cluster, inverted, that the artist used in A Bacchanalian Revel Before a Term) creates a counterpoint to the group of worshippers on the right, each one depicted by Poussin as caught up in the moment from a particular perspective. Poussin situates the reality of this picture – that feeling of time suspended – not in the narrative, or a protagonist, but in the awareness of the players.

The Adoration of the Golden Calf (1633–34), Nicolas Poussin. The National Gallery, London

Look at how attention splinters in different directions. The dancers link arms in an ecstatic hop, and their energy extends into the limbs of the central dancer, draped in white, who seems to reach out to invite the worshippers to join them. A few of the worshippers supplicate to Aaron, perhaps warning him about the appearance of his grumpy brother, while one woman in blue looks like she’s trying to tell the dancers to settle down and look at the calf. Others are talking among themselves, still more raise their arms in confusion or disbelief. The tree on the right, subtly anthropomorphic, raises its branches as if in alarm, echoing the figures below. The moment multiplies, suspended in the eyes and minds of everyone portrayed in the painting. Even the calf himself lifts his leg as if he’s about to join the dance, casting a bemused gaze at the worshippers below him. As a viewer, we register a range of simultaneous perspectives and meanings, and the painting invites us into this fragmented drama. We become another witness, another point of view. Compare The Adoration of the Golden Calf to Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus (1601), which also depicts an epiphanic moment from scripture. In Caravaggio’s work drama and pathos are unified by the central figure of Jesus. Poussin, by contrast, situates the narrative in countless different viewpoints. There is no hero, no psychological centre. Supper at Emmaus presents the denouement of a story with a protagonist that you watch from the outside, like a movie; The Adoration of the Golden Calf is polyphonic in its form, the story experienced from multiple perspectives simultaneously, each of equal importance.

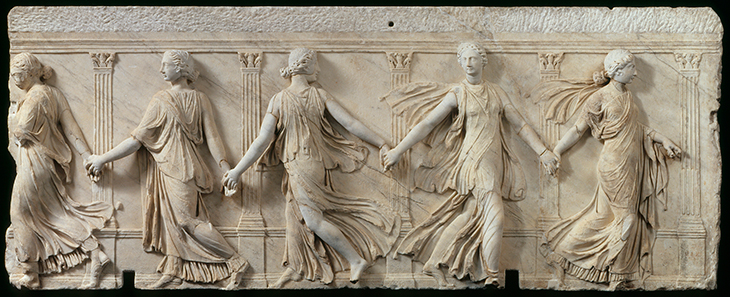

Relief with Five Dancers before a Portico (‘The Borghese Dancers’) (2nd century AD), Roman. Musée du Louvre, Paris. © RMN-Grand Palais

In ‘Animating the Frieze’, Francesca Whitlum-Cooper’s essay in the exhibition catalogue, she describes how Poussin based the dancers in A Dance to the Music of Time and A Bacchanalian Revel Before a Term (and thus The Adoration of the Golden Calf), as well as an extraordinary drawing Dance Before a Herm of Pan ([1628–30]; his first work to feature a ring of dancers, she argues) in part on a Roman sculpted frieze, the second-century Borghese Dancers. The Roman work was meant to look antique when it was made, a glance back at the golden age of Greece, already hundreds of years in the past. If you danced in ancient Rome, you were an entertainer, a job fit for slaves and prostitutes. For ancient Greeks, dance was at the heart of daily life, for rich and poor alike. Along a road to ancient Corinth there was a shrine that archaeological evidence suggests was dedicated to Pan and the Nymphs. Amid the many votive offerings discovered at the shrine are terracotta sculptures of circles of dancers, arms linked, surrounding a figure playing a syrinx, or pan pipe (c. 4th or 5th century BC). The works look quick and casual, childlike in their facture, and small enough to be held in the palm of one’s hand. Yet they also bring to mind Poussin’s rings of dancing figures. Poussin was not familiar with these particular sculptures (though it’s interesting to note that he made clay figures in his early years to rehearse his compositions), but the similarities are not merely coincidental. The difference between Greek and Roman culture was an ongoing debate even in 17th-century Rome. I’d like to think that by depicting dancers with such gusto Poussin was having a go at snooty Romans – both his contemporaries (for the hostile reception they gave him when he first arrived in the city), and the ancients, who were often contemptuous of the culture they so wholeheartedly absorbed. The artist was knowingly presenting a pre-Roman idea of pleasure, beauty and social cohesion.

A Dance to the Music of Time (c. 1634), Nicolas Poussin. The Wallace Collection, London. © The Trustees of the Wallace Collection

When Gian Lorenzo Bernini saw Landscape with the Ashes of Phocion in Paris (1648; it’s now in the Walker, Liverpool, and one of the greatest paintings in the UK), he pointed to his forehead and said, ‘Poussin is a painter who works from here.’ The usual interpretation of this event is that Bernini, the poster boy of baroque dynamism, declared Poussin an intellectual painter. But I have a different reading: he may have also sensed that Poussin works from – and into – the viewer’s imagination. Bernini felt that same sensation of being played by the painting, creating a particular awareness of space and time – the same astonishment I felt in front of The Triumph of Pan. Landscape with the Ashes of Phocion is also animated by echoes and rhymes between nature, art and human perception and morality. In The Triumph of Pan, Poussin thematises this force of an artwork to infuse the consciousness of a living thing. Look to the upper right of the painting, to the cluster of three trees. Two trunks on the far right extend straight upwards, beyond the top of the canvas, while a third, just to their left, extends its branches like limbs, as if dancing to the music below. (Recalling the anxious tree in The Adoration of the Golden Calf.) Between the anthropomorphic limbs there is an ovoid clump of wood; it is head-shaped, seemingly with eye cavities, and adorned by branches like horns. The clump is a direct echo in size and shape of Pan’s head from the central sculpture. The spirit of the mischievous god infuses the trees, as if nature itself couldn’t resist the shake of a tambourine. Likewise, the rhythm of Poussin’s paintings works its way into the viewer. We can read Poussin’s paintings, but before that intellectual task takes place we feel them as an analogue of embodied thought.

In June 1643, the artist wrote a letter to his patron Paul Fréart de Chantelou, who commissioned some of his greatest later paintings. Almost 50 and back in Rome after a short, unhappy stint as the court painter in Paris, he was in a reflective mood, observing that he ‘marvels’ at those who laugh rather than sigh in the face of misery and misfortune. He concludes the paragraph with the line, ‘Nous n’avons rien en propre, nous tenons tout à louage.’ (‘Nothing is truly ours, everything we hold is for hire.’) Poussin’s thoughts echo those of Epictetus, who in his Handbook advised that death, even that of a child, should not be treated as a loss but a return, a giving back to nature. It’s a stark and brutal sentiment, tough to take to heart, yet the Stoic recognition of relentless flux helps us to understand why Poussin made paintings filled with multiple stories and perspectives and granted such importance to the viewer’s imagination. Memories, myths, weeds on the side of the road, the curve of an arm, the anticipation of the dancers falling to their feet. Perception is always shifting, our place in the world unstable, our consciousness constituted of borrowed things. Maybe Pan’s grin betrays a hint of irony. He is laughing at loss, at the ephemerality of pleasure. But his eyes and smile also invite you into a world where time is suspended – and where anyone can dance with the god of unbridled wildness, briefly, in eternity.

‘Poussin and the Dance’ is at the National Gallery, London, from 9 October–2 January 2022.

From the October 2021 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

Has the Fitzwilliam lost the hang of things?