It’s the week before Christmas. The shops are heaving, drinks are flowing and carols are peeling. But amongst all the festivity it is easy to forget the religious story behind all this joyful consumerism: in a small town over two thousand miles away and over two thousand years ago, three magi presented treasures to a newborn baby, the King of the Jews; rich and symbolic gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. It’s a story that’s been represented in Western art time out of mind, and always overlaid with specific cultural associations and assumptions around kingship, around precious materials and about gift-giving.

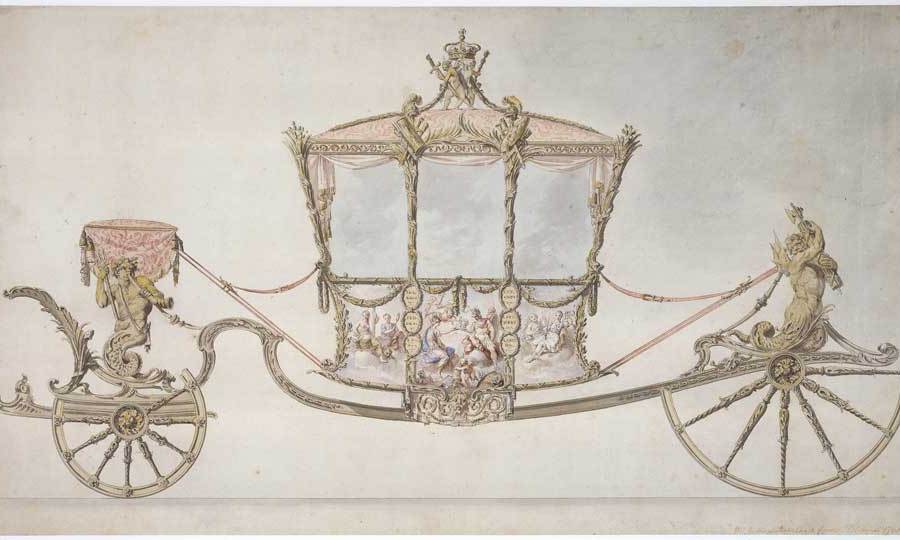

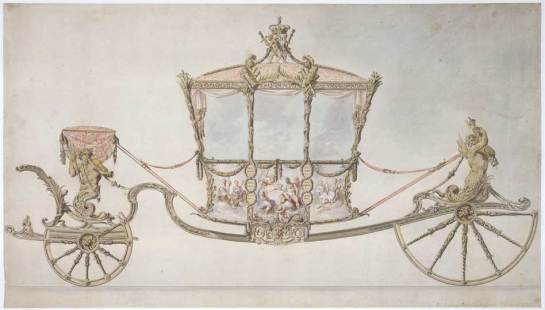

Queen Victoria Receiving the Sacrament at her Coronation, 28 June 1838 (1838–9), Charles Robert Leslie. Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014

So, amongst your holiday revelries, now is the perfect time to visit ‘Gold’ at the Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace: a small but alluring show considering the material history and symbolism of gold through 50 pieces from the Royal Collection. They range from the early Bronze Age to the 20th century, and consider gold from three perspectives: as a royal accolade, an artist’s material and a sacred ornament. The exhibition continues a trend to consider the power of a particular material in artistic production, following ‘Bronze’ at the Royal Academy in 2012 and the Saatchi Gallery’s ‘Paper’ in 2013.

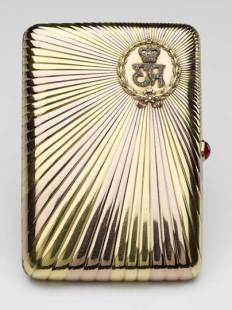

There are some stunning pieces, and also some surprises and interesting juxtapositions. You walk in to meet the more expected painting of Queen Victoria’s coronation by Charles Robert Leslie alongside an Ecuadorian crown created in the 11th–15th centuries and excavated in 1854. The extraordinary tiger head that once adorned Tipu Sultan’s throne is surrounded by Fabergé snuff boxes, William Chambers’ design for the coronation coach, and the well-known image of Misers counting their coins. The simplest and yet most beautiful object is the early Bronze Age ‘Rillaton Cup’ formed from a single ingot and worked with stone or bone tools to create corrugated bands that reflect the light.

The versatility and appeal of gold as a material is stressed. Able to be cast, beaten, burnished, drawn into wires, laid onto pages in the thinnest gold leaf or mixed with alloys to create different colours, gold also has deep symbolism due to its purity, rarity and reflective nature. It is these qualities, of course, that make it attractive to artists, monarchs and pontiffs alike, as it demonstrates skill, confers wealth and status, and symbolises immortality and incorruptibility.

These are the qualities that make gold a perfect gift for the Son of God, presented as coins, elaborate objects, or pure metal by painted Magi down the ages. But the gifts given to the Christ Child have also always fascinated me with their complex power associations of conflict, trade and empire. Mantegna’s small Adoration of the Magi that ends the British Museum’s current ‘Ming’ exhibition brilliantly makes this point about the power of a rare, expensive and culturally-charged material like porcelain, appearing simply in the painting as the container for the oldest Magi’s gift of gold.

This angle is oddly absent from the ‘Gold’ exhibition. Tipu’s tiger and the Ecuadorian crown are both there, after all, as official presents to the British monarch from countries changed forever by European colonisation. Other objects were made specifically as part of coronation ceremonies by powerful London livery companies, or acquired for the crown as Treasure Trove. Here are some of the darker sides of precious materials and symbolic objects, bound up with political power, exchange and exploitation, which we do well to remember at Christmas amongst all the wrapping paper.

‘Gold’ is at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, until 22 February 2015.

Related Articles

Paper Tigers: ‘Paper’ at the Saatchi Gallery (Hannah Levett)

Review: ‘Ming: 50 years that changed China’ at the British Museum (Alice Williamson)

Unlimited access from just $16 every 3 months

Subscribe to get unlimited and exclusive access to the top art stories, interviews and exhibition reviews.

![Masterpiece [Re]discovery 2022. Photo: Ben Fisher Photography, courtesy of Masterpiece London](http://www.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/MPL2022_4263.jpg)

It’s time for the government of London to return to its rightful home